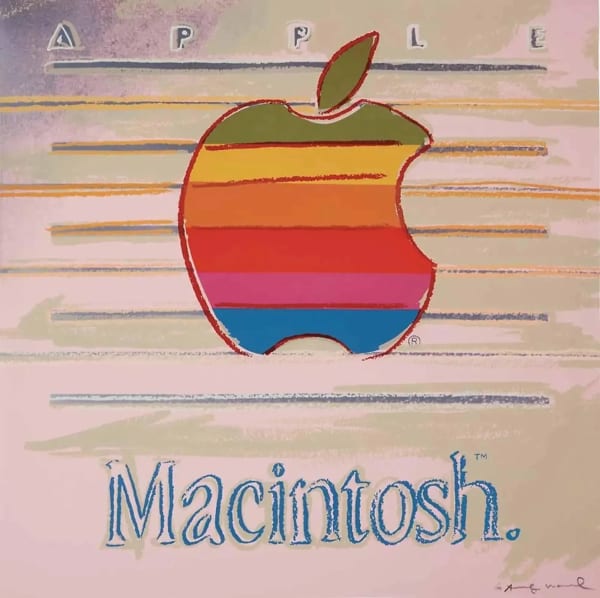

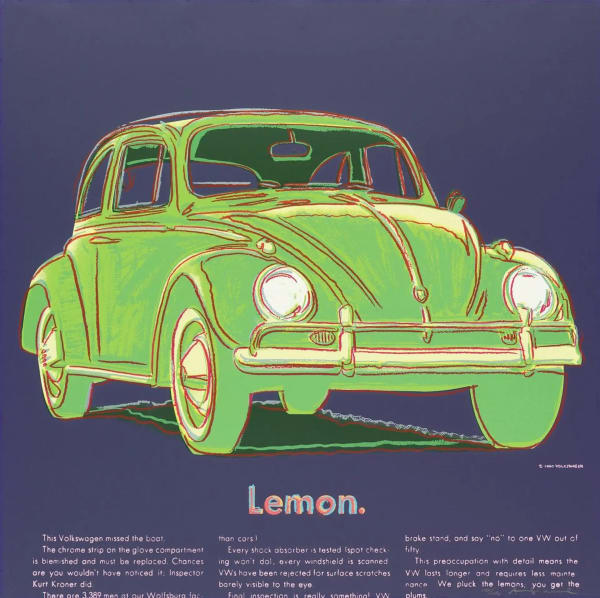

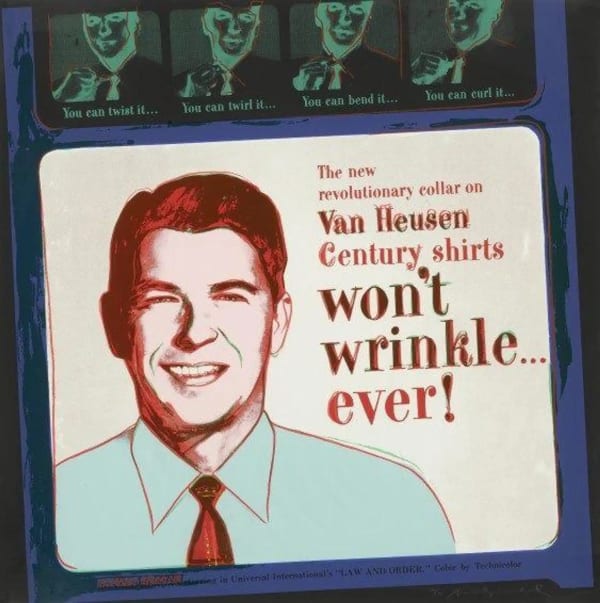

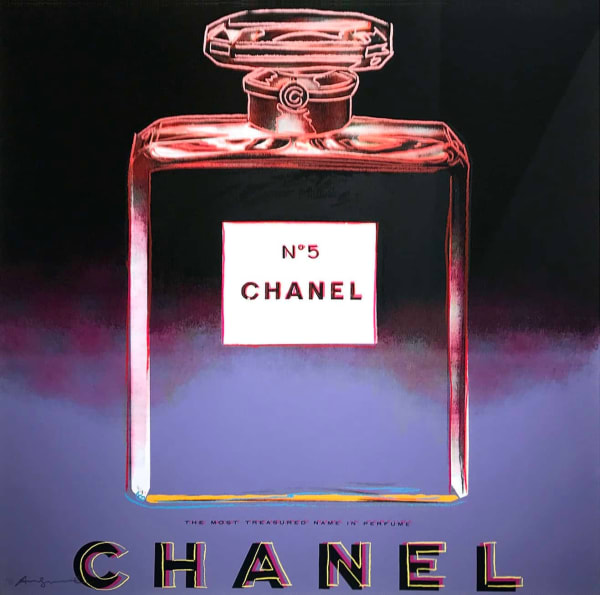

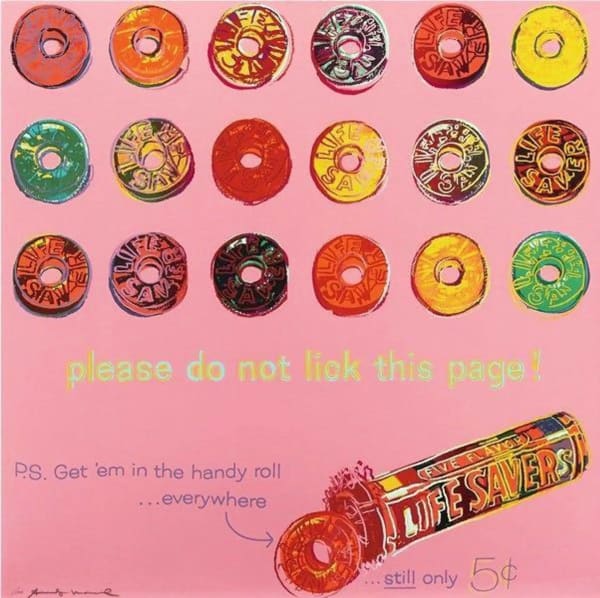

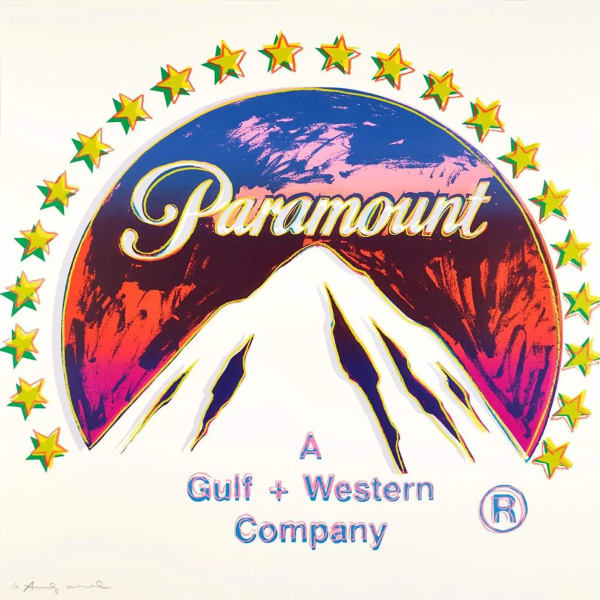

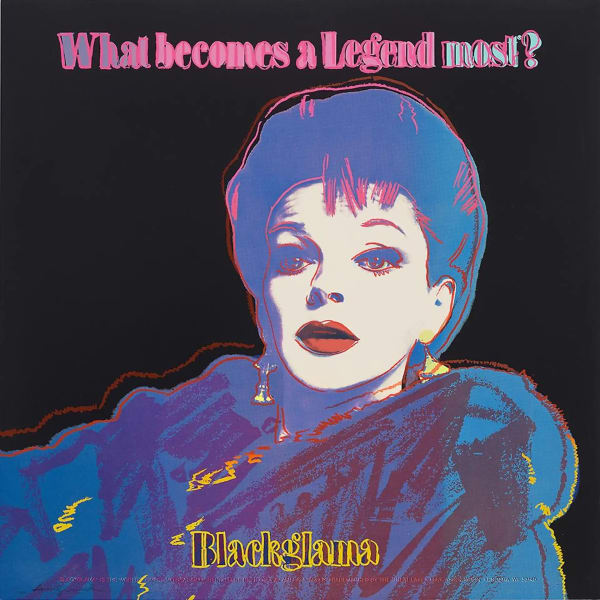

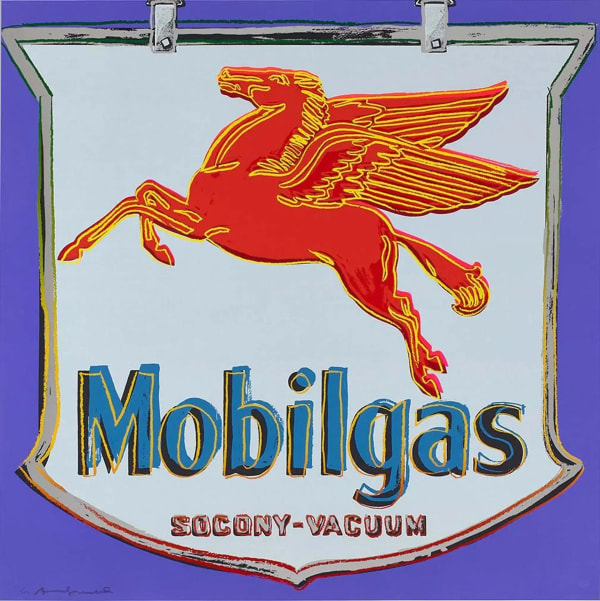

Andy Warhol’s Ads portfolio, created in 1985, stands as one of his final and most conceptually sophisticated statements—a culmination of his lifelong dialogue between art, commerce, and celebrity. In this ten-screenprint series, Warhol reimagines some of the most recognizable advertisements of the 20th century, including Chanel No. 5, Paramount Pictures, Van Heusen, Volkswagen, and Apple. By elevating these sleek symbols of consumer culture to the realm of fine art, Warhol not only celebrates the visual language of modern advertising but also exposes its pervasive influence on identity, aspiration, and taste.

The Ads portfolio can be read as a summation of Warhol’s artistic philosophy. From the Campbell’s Soup Cans of the 1960s to the Mao portraits of the 1970s, Warhol had always been preoccupied with the machinery of fame and repetition. In Ads, he brings this full circle, turning the logos and slogans of corporate America into cultural icons—no less significant than the celebrities who once appeared in his work. The series demonstrates Warhol’s acute understanding that advertising had become the new mythology of the modern age, shaping not only what people buy but what they believe in.

Visually, the prints are electric—layering vivid color, bold type, and gleaming imagery in a way that mirrors both the seduction and saturation of mass media. Conceptually, they mark Warhol’s recognition that art itself had become indistinguishable from marketing, a prediction that feels increasingly relevant in the digital era. Nearly forty years later, Ads remains one of Warhol’s most culturally resonant portfolios: a vibrant, ironic reflection on the power of branding and a prescient reminder that in Warhol’s world—and ours—the advertisement is both artifact and art, promise and portrait of an age obsessed with image.