Christopher Makos occupies a singular position in the landscape of late twentieth-century photography, bridging documentary clarity with a flair for experimentation that feels unmistakably his own. Best known for his close relationship with Andy Warhol and his extensive documentation of the Factory scene, Makos brought a sharp, modern sensibility to portraiture at a moment when art, fashion, celebrity, and subculture were converging in unprecedented ways. His work reveals a rare balance: on one hand, an instinctive photojournalistic ability to capture the truth of a person in an instant, and on the other, a conceptual interest in how identity is constructed through images. This dual approach animates not only his iconic portraits but also his collage works, which expand the language of photography into something more fluid, layered, and reflective of their cultural moment.

Makos’ artistic foundation was shaped by two powerful influences. The first was his early exposure to European avant-gardism, particularly through his mentorship under Man Ray. This connection instilled in him a respect for photographic experimentation and the idea that a portrait could be not just representational but transformative. The second was his immersion in New York’s downtown art community, where he forged friendships with Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry, and other emerging cultural figures. Makos’ camera became both a document of and an invitation into this world, producing images that now serve as essential visual records of one of the most creative eras in American art. His photographs, whether candid or staged, reflect an intuitive understanding that he was capturing people not only as they were, but as they would eventually be remembered.

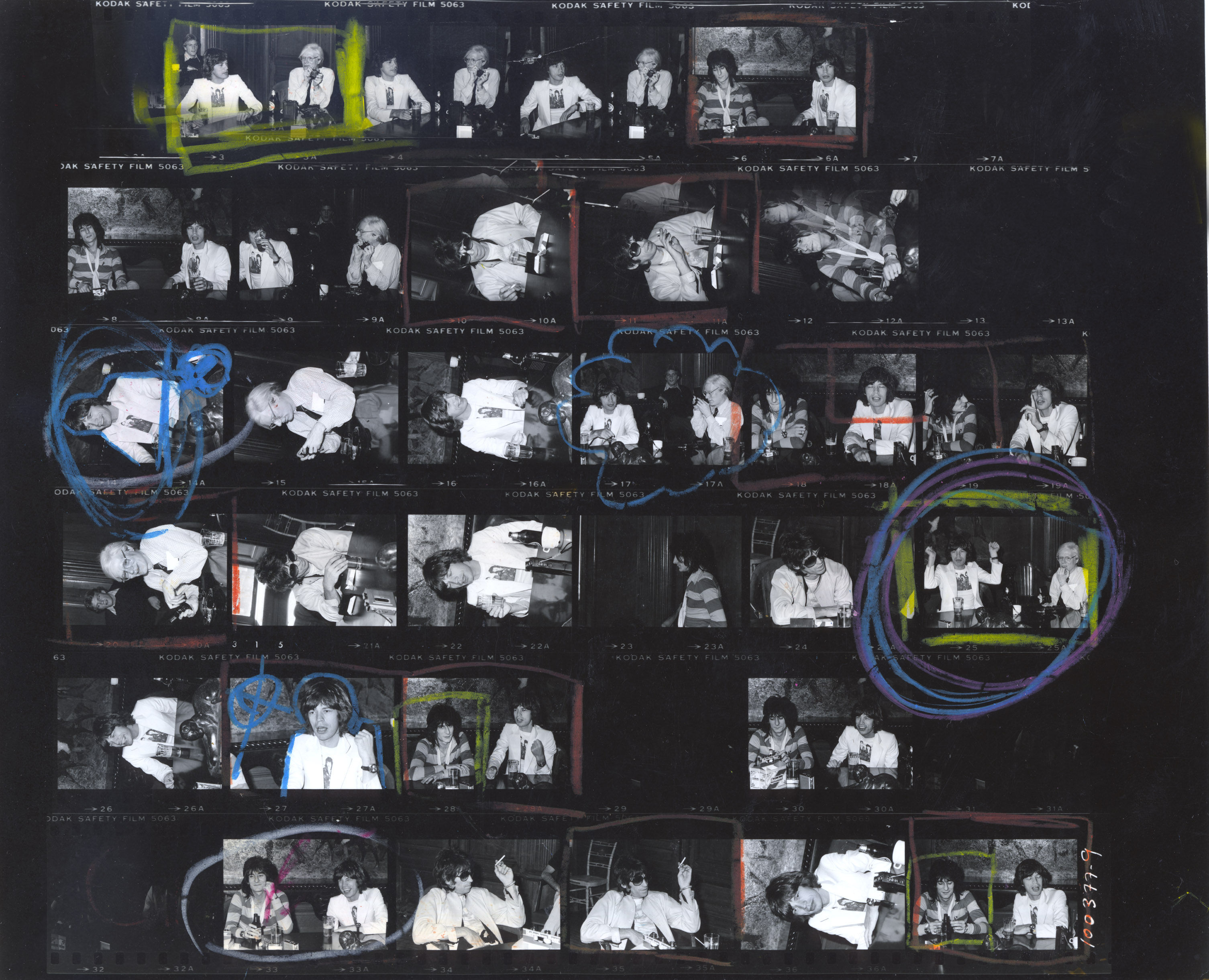

This sensitivity is especially present in his collage works, which operate like visual archives: dense, layered, and charged with time. Rolling Stones Andy Warhol Factory Lunch, 1977 is a prime example. Created during the height of Warhol’s cultural influence, the work is both a portrait of a specific moment and a commentary on the ecosystem that surrounded Warhol. The collage brings together fragments that feel casual yet deliberate—faces, gestures, and glimpses of the Factory’s atmosphere—suggesting that the mythology of Warhol was composed as much through fleeting interactions as through finished artworks. Makos’ approach here is almost anthropological. Rather than presenting a single, definitive image, he offers accumulation. The result is a dynamic representation of social history, one that acknowledges that the Factory’s power lay in its collaborative, chaotic, and often contradictory nature.

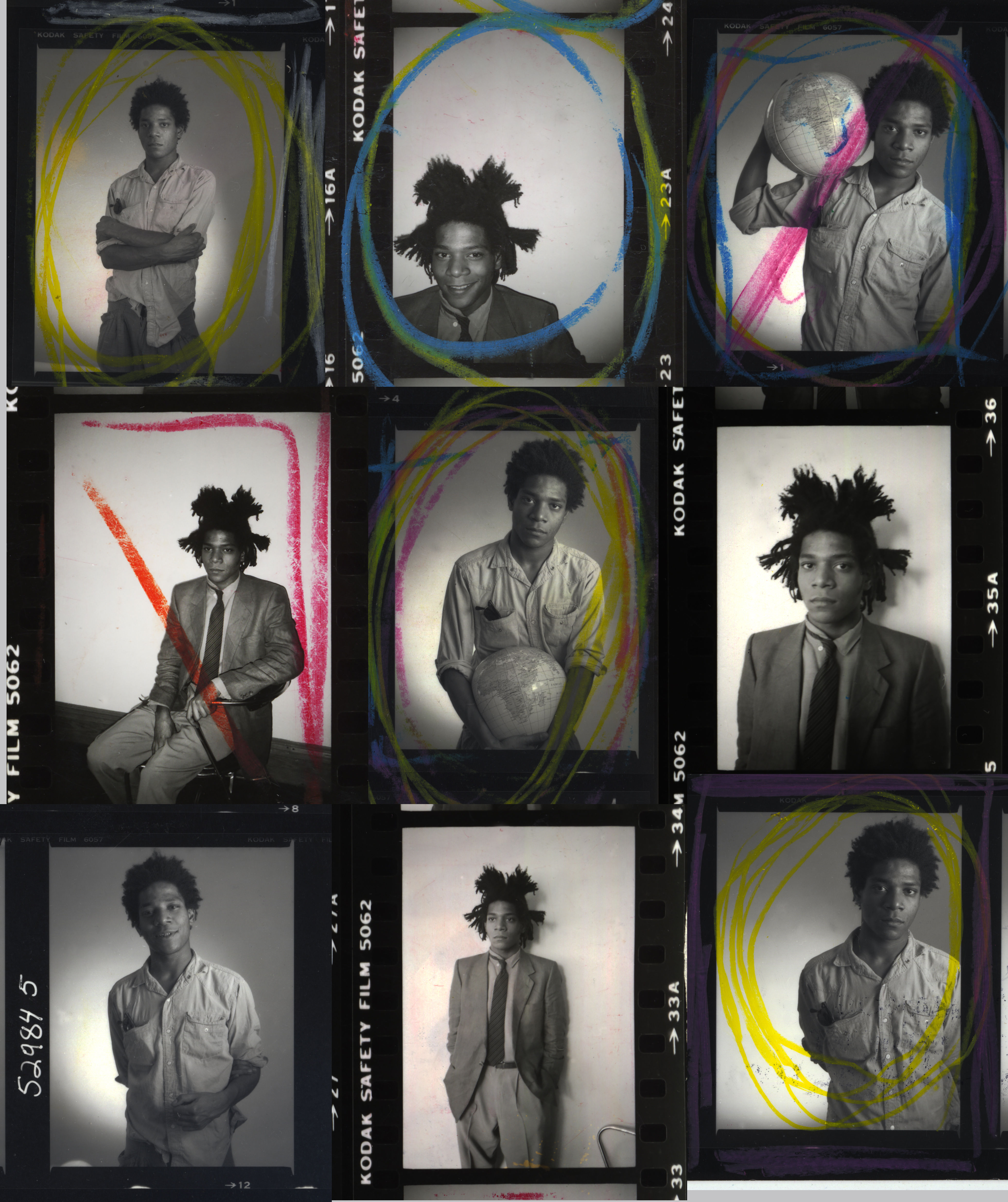

In Basquiat, Haring, 2025, Makos extends this visual language across time. By bringing these fragments together decades later, he explores how cultural memory is assembled. The collage becomes a meditation on what is preserved, what is lost, and how an artist’s image evolves once it becomes entrenched in public consciousness. The work highlights Makos’ capacity to move between the personal and the historical, treating photography not simply as a record but as an active participant in art history.

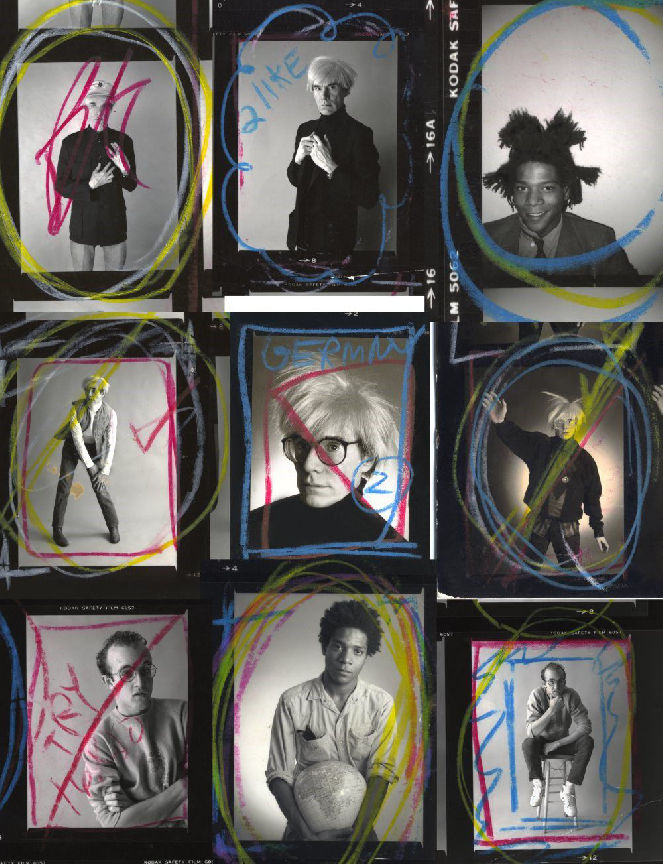

Andy, Basquiat, Haring, Threesome, 2023 continues this exploration of legacy but adds Makos’ characteristic sense of play. Here, the collage format becomes almost conversational. Three icons of late twentieth-century art share a visual space that collapses decades of creative exchange into a single composition. Makos is uniquely positioned to orchestrate such a moment. He photographed all three artists during formative times in their careers, capturing their personalities, their contradictions, and the different ways they navigated fame and artistic ambition. In the collage, these threads intertwine. Warhol’s enigmatic presence, Basquiat’s intensity, and Haring’s graphic immediacy coexist not as historical footnotes but as living energies. The work highlights Makos’ ability to create dialogue across eras, turning the collage into a site of cultural reunion.

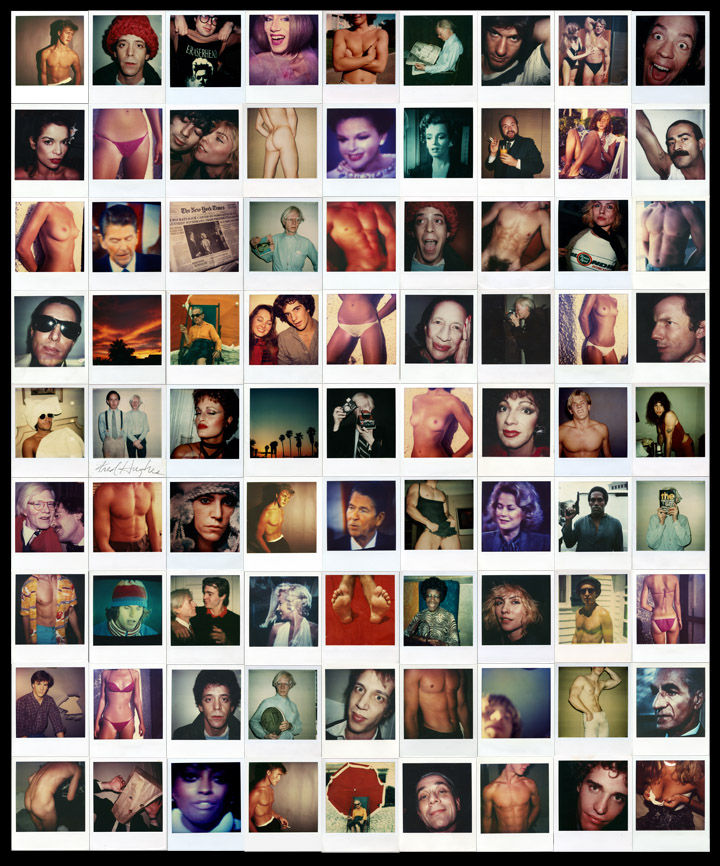

Perhaps the most expansive of these works is Portraits of an Era, Polaroid Collage #1 (81 Portraits), 1975–1984. This collage is less a single artwork and more an entire ecosystem of faces, moments, and gestures. Composed of eighty-one Polaroids spanning nearly a decade, it maps the interconnected social and artistic networks of the time. Polaroids were central to Makos’ practice: immediate, unfiltered, and intimate, they allowed him to capture the spontaneity of life in New York with unparalleled freshness. Arranged together, these portraits form a collective portrait of an era defined by experimentation, nightlife, and artistic reinvention. The collage format emphasizes the democratic nature of Makos’ gaze. Celebrities, downtown artists, and anonymous figures all appear with equal visual weight, underscoring his belief that cultural history is shaped not only by its stars but by the full constellation of personalities around them.

What unites these collage works is Makos’ understanding that photography is never fixed. A single image can freeze a moment, but a collage acknowledges the complexity of lived experience. It suggests that memory is multiple, layered, and sometimes contradictory. Makos uses the collage not as decoration but as structure—an architecture for organizing cultural memory. His works operate like visual timelines that viewers can read from multiple directions, discovering new relationships and resonances with each pass. This approach sets Makos apart from many photographers of his generation. While others documented the era, Makos actively shaped how that era would be remembered.

Across his career, Makos has insisted on showing people as they were, but also as they imagined themselves to be. His photographs capture vulnerability and performance in equal measure. His collages reveal how those performances accumulate to create cultural myth. Together, they form an indispensable record of a generation that redefined contemporary art. And yet, Makos’ work is not nostalgic. It feels alive, open, and in motion—an ongoing conversation between the past and the present.

Through his lens, Makos transformed the everyday into something historical, and the historical into something deeply personal. His collage works in particular serve as reminders that art does not simply preserve time; it reshapes it, reorganizing the fragments into stories that continue to evolve with every viewer.