John Baldessari spent six decades proving that pictures don’t just show the world, they teach us how to see it. A towering figure of Conceptual art, he blended photography, painting, film stills, text and blocks of color into works that are at once dryly funny and deeply analytical. His images seem simple - faces covered with colored dots, hands and legs cropped mid-gesture, movie stills interrupted by words - but they quietly rewire how we think about images, narrative and authorship.

For collectors, Baldessari is not only an art-historical heavyweight but also a mature, well-documented market. His works range from seven-figure paintings to comparatively accessible prints, all supported by decades of institutional recognition, teaching influence and resilient auction performance.

Born in 1931 in National City, California, Baldessari began as a fairly traditional painter in the 1950s. By the mid-1960s, he was increasingly frustrated with conventional painting and started producing text-based canvases - deadpan statements about art theory that were hand-lettered by professional sign painters. These early text pieces were his first decisive move toward Conceptual art, deliberately stripping away expressive brushwork in favor of cool, “commercial” language.

The real rupture came in 1970 with the now-legendary Cremation Project. Baldessari took all of the paintings he still owned from 1953–1966 to a crematorium and had them incinerated, placing the ashes into an urn and even baking some into cookies. He treated the act as both artwork and self-erasure, marking what he later called the real beginning of his career. From that point on, he devoted himself to photographic imagery, film, text, printmaking and installation, testing “the structure of art, images and language” for the next five decades.

Parallel to his studio work, Baldessari was a legendary teacher. He helped shape the visual arts program at the University of California, San Diego and then joined the founding faculty at CalArts, where his famously open-ended “Post Studio” class encouraged students to think beyond traditional mediums. Many future stars - David Salle, Mike Kelley, Jack Goldstein, Barbara Bloom, and others - passed through his classroom.

By the time of his death in 2020, Baldessari had exhibited in more than 200 solo shows and 1,000 group exhibitions worldwide, received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2009, and been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Baldessari’s work is deceptively simple to describe and endlessly rich to unpack. A few key strategies define his practice:

1. Text + image

In the late 1960s he painted short phrases - “Tips for Artists Who Want to Sell,” “A Two-Dimensional Surface Without Any Articulation Is a Dead Experience” - on monochrome canvases, the language lifted from art manuals or theory. By outsourcing the lettering to sign painters, he removed his “hand” and turned the statement itself into the artwork.

Later, he began pairing photographs with captions that either over-explained, contradicted or derailed what you saw. The gap between word and image forced viewers to do conceptual work - completing a joke, inventing a narrative, or noticing how quickly we trust language.

2. Appropriation and cropping

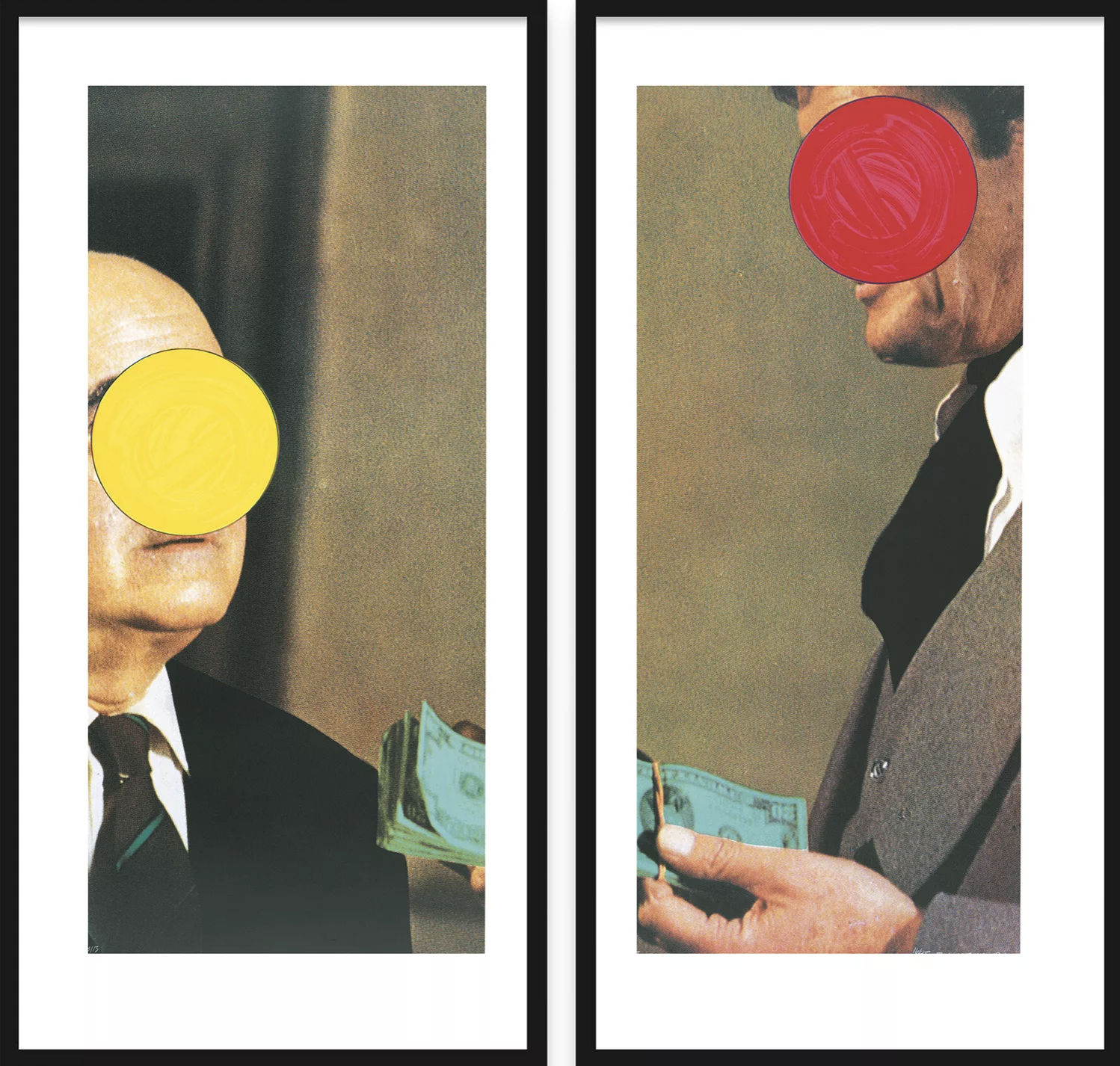

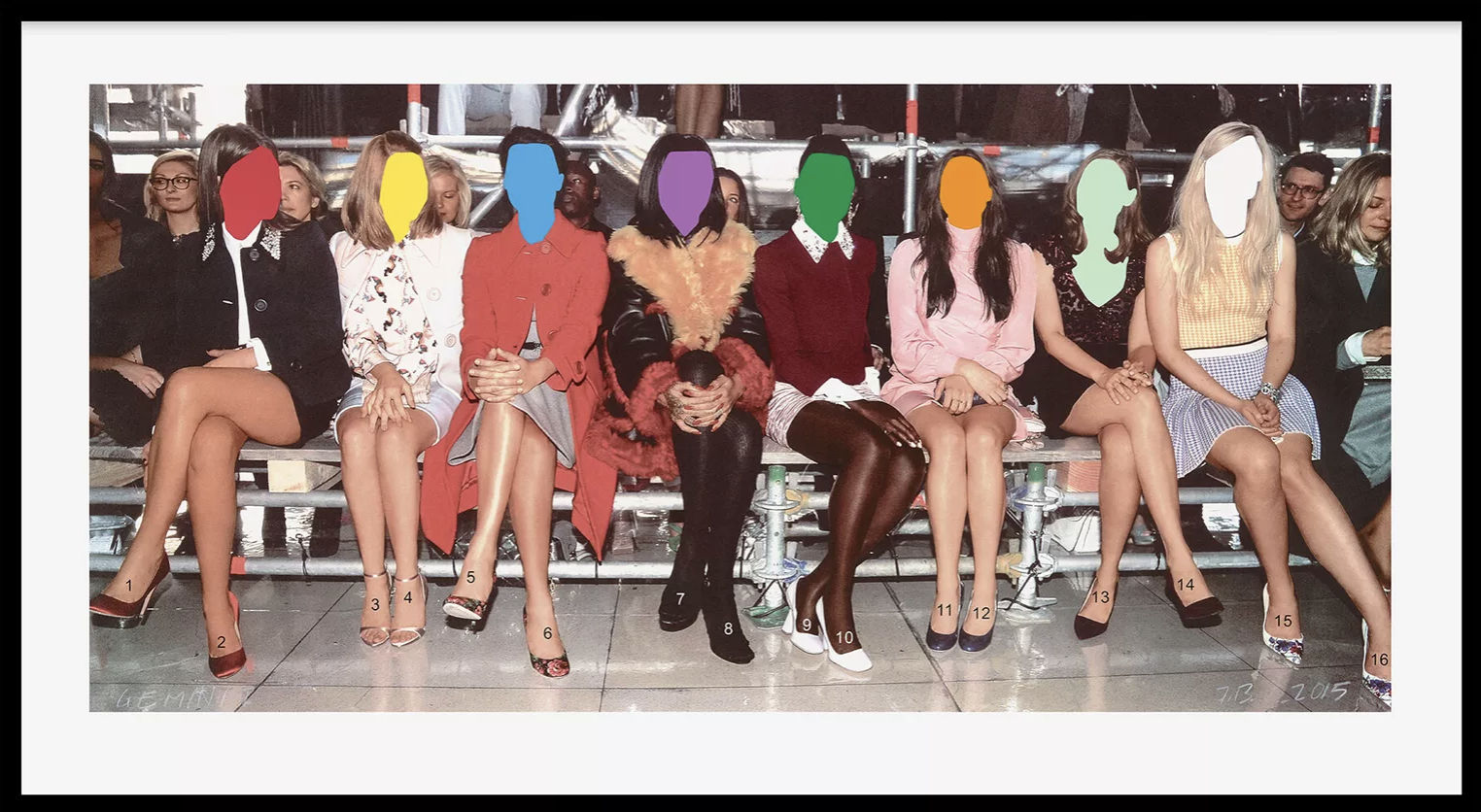

From the 1970s onward, Baldessari made extensive use of found photographs and movie stills. He cropped off heads, isolated legs, or focused on hands mid-gesture, turning everyday scenes into odd, suspenseful fragments. In works like Money (with Space Between) or Front Row: Numbered Legs, identity is reduced to posture and clothing; the “story” is what the viewer projects into the missing pieces.

3. Color dots and visual obstruction

Perhaps his most recognizable gesture is the colored dot over a face - bold circles of red, yellow, blue or green that erase individual identity while sharpening our awareness of composition. By blocking the very thing we are trained to look at (the face), he forces attention onto secondary details: a hand, a prop, a background clue. This playful censorship becomes a tool for re-composing reality.

4. Seriality and repetition

Baldessari often repeated the same image in grids, changing color overlays or text from panel to panel, much like musical variations. Works such as The Concerto for Two use rhythm and repetition to suggest a visual “score,” underlining his fascination with how sequences of images create meaning over time.

Despite the conceptual rigor, one of the most striking things about Baldessari’s work is how accessible it feels. As Artforum noted, his pieces can be enjoyed “just as readily by laypeople as by conceptual cognoscenti”; you don’t need a PhD to get the joke or feel the puzzle.

Baldessari described himself less as a painter and more as an editor or arranger. Many works began with an archive of found images - press photos, film stills, stock photography - that he would cut, crop, enlarge and recombine. Text was added, removed, or shifted until the right balance of clarity and ambiguity emerged.

He frequently collaborated with master printers and workshops for his editions (Gemini G.E.L., among others), using lithography, screenprint, archival inkjet and photo-based processes to achieve crisp, reproducible images while still allowing for interventions like hand-applied color or embossing.

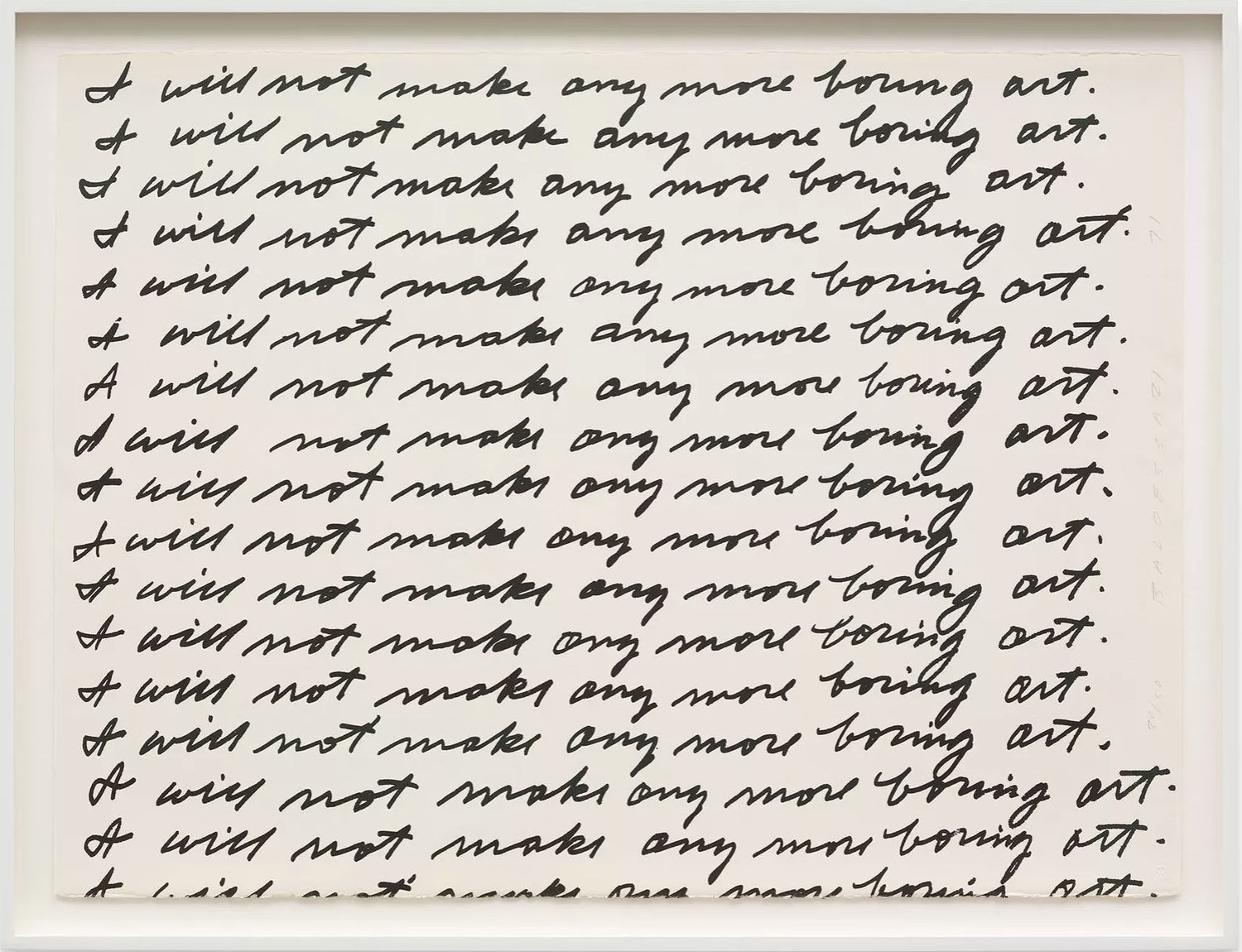

Humor was central to his method. Baldessari believed that making people smile opened them up to more complex ideas. Works like I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971) - a phrase he wrote repeatedly on a gallery wall like a school punishment - mock both art-world solemnity and his own role as teacher, while still delivering a serious manifesto.

From the 1970s onward, critics recognized Baldessari as a key bridge between Pop, Conceptual art and later generations of photo-based practice. The Guardian called him “a towering figure in conceptual art” whose work spanned painting, photography, film, video, books and public sculpture.

Institutions worldwide hold his works in their collections, including the Tate, MoMA, the Broad, LACMA, and many others. The Broad, for instance, characterizes his post-Cremation work as a sustained attempt to explore “a realm of activity which had no boundaries,” emphasizing his role in expanding what counted as art in the late 20th century.

Critics often highlight two things: his rigorous questioning of how images function, and his refusal to let Conceptual art become dry or esoteric. Artforum praised the way his work offers “systematic bewildering” that is still legible and enjoyable, while other writers point to his influence as a teacher in shaping the language of contemporary art critique itself.

Baldessari’s market is relatively mature and well-documented, spanning unique works, editions and more experimental objects. Since the late 1990s, his auction prices have climbed steadily, with several landmark results:

-

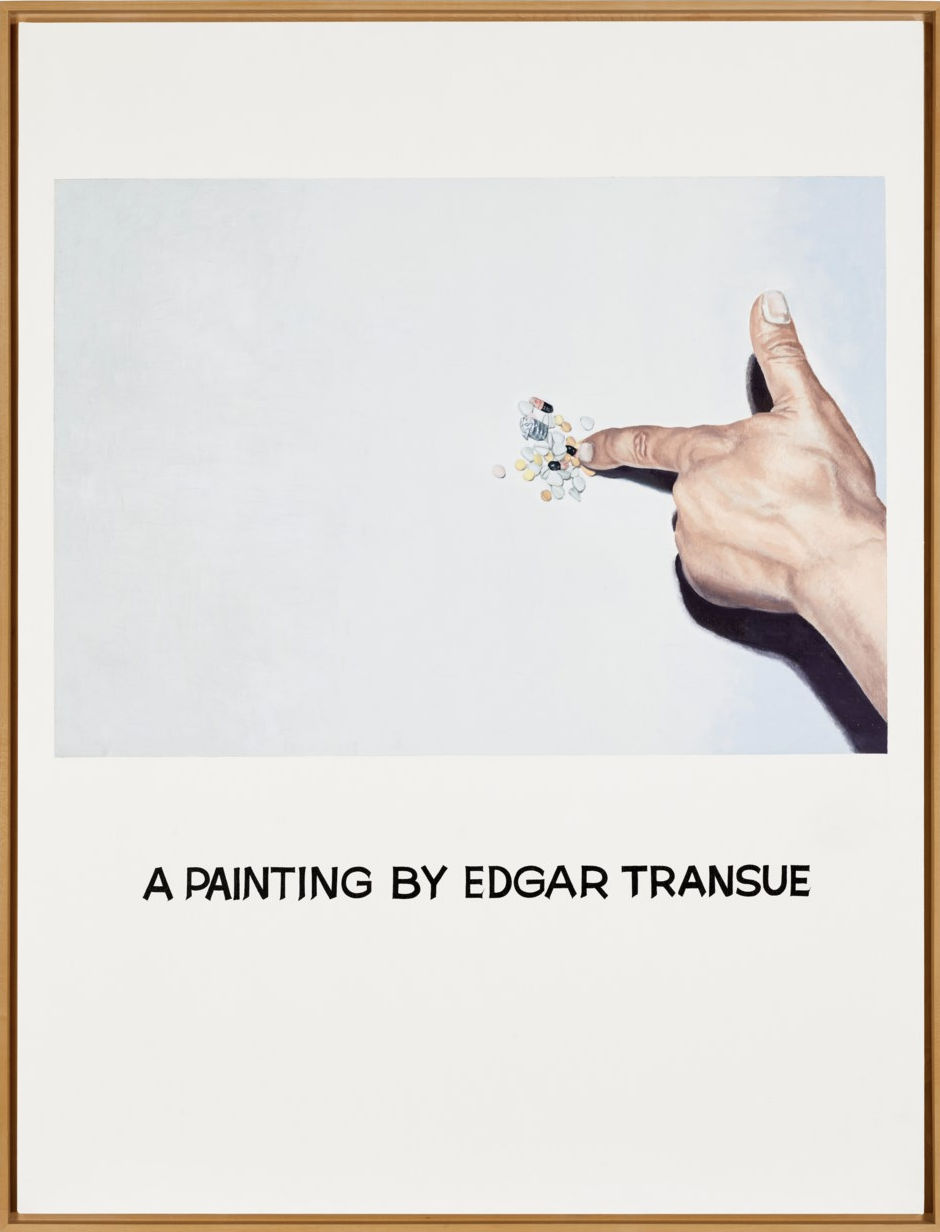

According to MutualArt, his auction record stands at $2,517,000 for Commissioned Painting: A Painting by Edgar Transue, sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2014.

-

Market analyses note that his early conceptual works from the 1960s command the highest prices, with strong demand also for his 1980s photo-based pieces.

-

Over the last year, Baldessari’s paintings have averaged around $65,000 at auction, with sculptures in a similar range and prints trading at lower but healthy levels - offering entry points for new collectors.

Platforms like Artsy and major houses such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s show a long track record of sales across categories, indicating sustained liquidity rather than sporadic spikes.

Of course, past performance never guarantees future returns, but the depth and consistency of his secondary market position him among the more established post-war artists.

Baldessari is widely acknowledged as one of the architects of Conceptual art and a crucial figure in the development of photo-based practices. His influence on subsequent generations - as teacher, mentor and model - is unusually well documented. That kind of canonical status tends to support long-term interest.

Major museums collect, exhibit and publish his work, and he has been the subject of major retrospectives, including the touring exhibition Pure Beauty (Tate/LACMA, 2009–2011). Institutional validation often aligns with stable or growing market interest over time.

Because Baldessari worked in many mediums and produced a significant number of prints and editions, his market has multiple tiers:

-

Top-end unique works (large photo-text pieces and early conceptual paintings) for major collectors and institutions.

-

Mid-tier photographs and collages that carry his signature strategies - dots, cropping, appropriated imagery.

-

Prints and editions produced with important workshops, which are more accessible yet still clearly part of his core practice.

This depth means new buyers can enter at lower price points and potentially trade up, while established collectors can target key historic works.

Conceptual art sometimes struggles in the market because it can appear dry or overly theoretical. Baldessari is an exception: his images are graphically strong, often colorful, and instantly memorable, even for viewers unfamiliar with art theory. That combination - critical depth and visual punch - helps his work live well in homes, not just museums, which matters for private collecting.

With the artist’s passing in 2020, his oeuvre is finite, and estates and galleries typically manage supply more carefully. Early analyses of his market during and after the 2020 economic shocks show that demand remained robust, with sales in the first half of that year reaching a significant portion of pre-crisis levels - an indication of resilience.

If you’re considering acquiring a Baldessari work, a few practical points:

-

Prioritize provenance and documentation. Look for works with clear exhibition and publication histories, or produced with recognized presses (Gemini G.E.L., El Nopal, etc.).

-

Understand the key series. Early text paintings, photo-text works of the 1970s, the colored-dot portraits, film-still collages, and later large-scale photo-montages each occupy different tiers of importance and price.

-

Condition matters. Many works are photo-based or on paper; professional framing and UV protection are essential.

-

Align with your taste. Because the market is broad, it’s possible to choose pieces that genuinely resonate with you - whether the quietly ironic text works or the playful, colorful image grids.

John Baldessari changed what art could look like and what it could do, all while insisting that it didn’t have to be boring. His work dismantles the mechanics of images - how they persuade, mislead, and entertain us - yet never forgets to be visually engaging and often very funny.

For collectors, Baldessari offers a rare mix: blue-chip conceptual significance, a long, well-documented market, and artworks that hold their own on the wall as much as in the history books. Whether you’re drawn to the early text canvases, the iconic color-dot photographs, or the later cinematic collages, investing in his work is, for many, a way to own a piece of the story of how contemporary art learned to think about pictures - and to laugh at them, just a little, along the way.

For more information on currently available John Baldessari artwork, contact our teams via info@guyhepner.com. Alternatively, if you wish to sell your Baldessari we can help. Speak to our New York and London teams today for a complimentary appraisal.