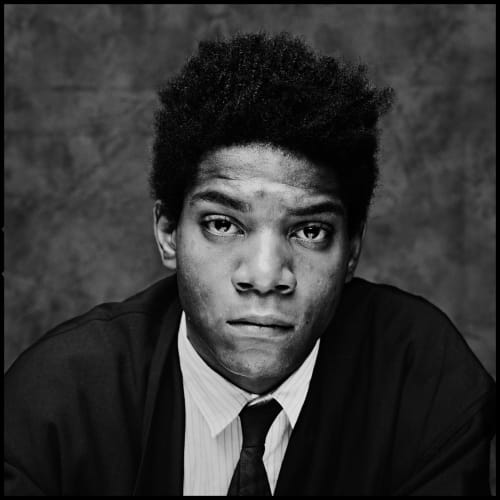

Few artists have reshaped the visual and cultural language of the late 20th century as powerfully as Jean-Michel Basquiat. In a brief yet incandescent career, Basquiat turned street iconography into fine art, redefined the role of Black identity in Western painting, and bridged the worlds of graffiti, jazz, poetry, and high fashion. His work continues to command record prices, provoke critical debate, and inspire generations of artists.

This A–Z guide explores the essential people, places, ideas, and artworks that define Basquiat’s enduring legacy.

A – Anatomy

Basquiat had an obsession with anatomy that stemmed from his childhood. After being hit by a car at age seven, he spent months recovering and studying Gray’s Anatomy, a medical book gifted to him by his mother. Anatomical references — bones, skulls, musculature, internal organs — became recurring symbols in his paintings, functioning both as metaphors for vulnerability and as commentaries on racial visibility. In works like Untitled (Skull) (1981) and Flexible (1984), dissected figures seem both human and divine, exposing the fragility beneath the myth of Black invincibility.

B – Black Identity

Central to Basquiat’s art is the reclamation of Black identity within a Eurocentric art world. He transformed the Black body into a site of empowerment, not erasure. His paintings celebrate Black musicians, athletes, and heroes — from Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie to Jesse Owens and Muhammad Ali — while also indicting historical systems of exploitation. Works like Irony of Negro Policeman (1981) and Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) (1983) confront institutional racism and internalised oppression. His art was, in many ways, a form of visual protest — an act of resistance rendered in oil stick and acrylic.

C – Crown

The three-pointed crown is perhaps Basquiat’s most recognisable symbol. Appearing across hundreds of works, it serves as a universal signifier of greatness — particularly of Black excellence in culture, music, and sport. Whether placed above a saintly jazz musician or hovering over a skeletal figure, the crown declares sovereignty and self-worth. Basquiat’s crowns also subvert the art-historical canon, crowning figures who were excluded from traditional hierarchies of power. The motif, simple yet profound, became his personal emblem of recognition and remembrance.

D – Downtown Scene

Basquiat’s rise was inseparable from the vibrant Downtown New York scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s — a crucible of punk, graffiti, and experimental art. Soho and the East Village teemed with cross-disciplinary creativity. Basquiat moved fluidly between these worlds, frequenting CBGB, Mudd Club, and Fun Gallery, where he mingled with musicians, filmmakers, and graffiti legends. This period forged his aesthetic: a synthesis of street energy and painterly sophistication that blurred the boundary between the avant-garde and the underground.

E – Expression

Basquiat’s work is raw, emotional, and direct. He approached the canvas like a stage, channeling anger, wit, intellect, and vulnerability through bold colour and gestural mark-making. Influenced by Abstract Expressionism yet rooted in street immediacy, his compositions teem with scrawled words, crossed-out phrases, and fragmented figures. Each brushstroke seems urgent, reflecting the rapid fire of his thoughts — a fusion of poetry, rhythm, and protest. This expressive force remains one of his defining achievements.

F – Fame

Fame came quickly — and destructively. By 1982, at just 22, Basquiat was exhibiting internationally, represented by Annina Nosei in New York and Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich. He appeared on magazine covers and moved in celebrity circles with Andy Warhol, Madonna, and Keith Haring. Yet fame also amplified the pressures of race and class in a predominantly white art world. Critics exoticised him as a “primitive genius,” a label he both benefited from and detested. His meteoric success mirrored his collapse — a tension that continues to haunt his mythology.

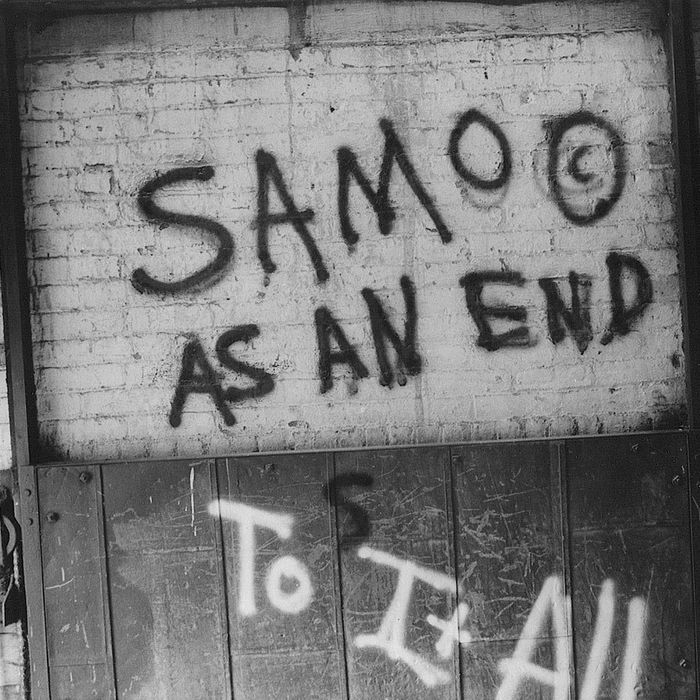

G – Graffiti and SAMO©

Before becoming a gallery sensation, Basquiat was one half of SAMO© (“Same Old Shit”), a graffiti duo he formed with high-school friend Al Diaz. Between 1977 and 1980, their cryptic, poetic slogans — “SAMO saves idiots,” “SAMO© as an end to mindwash religion, nowhere politics and bogus philosophy” — appeared across Lower Manhattan. These text-based interventions anticipated Basquiat’s later interest in language and subversion. When he publicly announced “SAMO is dead” in 1980, he was symbolically reborn as Jean-Michel Basquiat, the painter.

H – Heroes

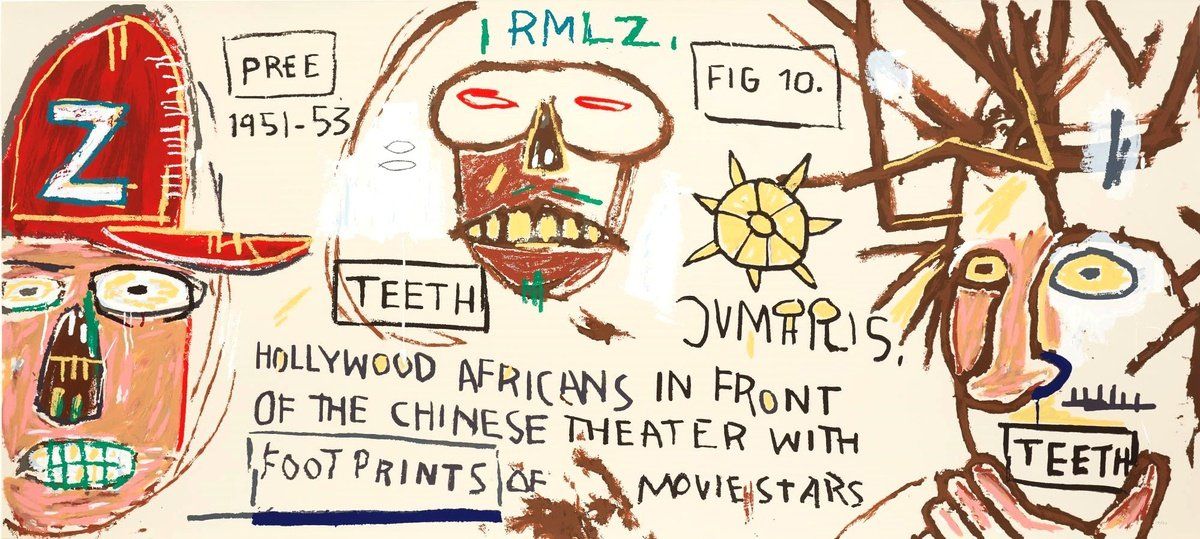

Basquiat’s pantheon of heroes spanned Black icons, boxers, jazz musicians, saints, and kings. His canvases pay homage to figures like Charlie Parker, Hank Aaron, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Joe Louis — men who broke barriers and redefined excellence. In Hollywood Africans (1983), Basquiat portrayed himself alongside Toxic and Rammellzee, reclaiming agency within an entertainment industry that often caricatured Blackness. His heroes are depicted with halos, crowns, and radiating lines — sanctified, deified, immortalised.

I – Irony

Irony permeates Basquiat’s language. He juxtaposed childlike drawings with complex historical references, humour with brutality, elegance with chaos. Titles such as Per Capita or Profit I mock capitalism and cultural commodification. His use of repetition, misspelling, and crossed-out text turns language into a weapon — revealing how meaning is constructed and manipulated. Beneath the surface play lies deep critique, exposing contradictions in art, race, and power.

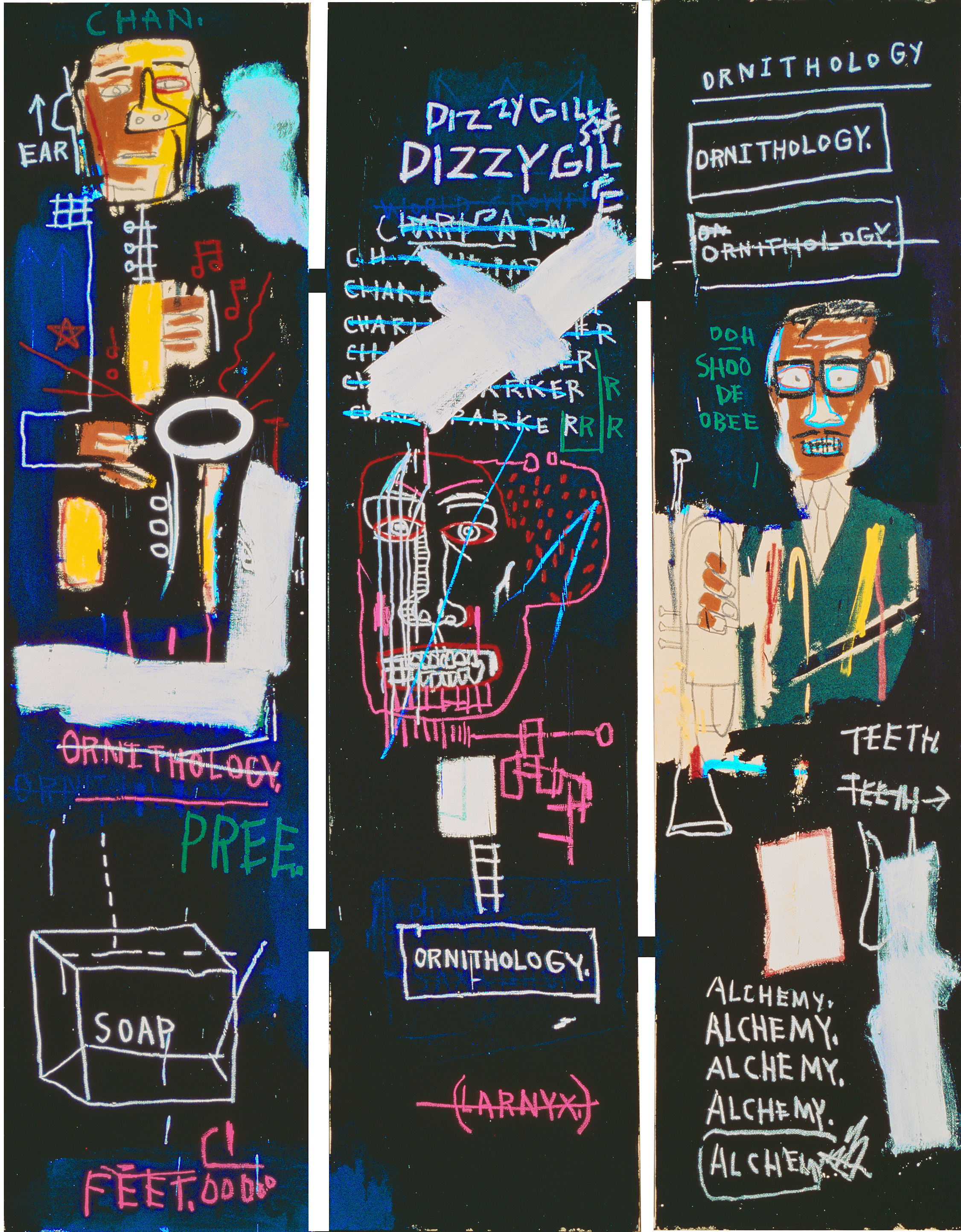

J – Jazz

If painting was his voice, jazz was his rhythm. Basquiat painted to a constant soundtrack of bebop, and the syncopated energy of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Charlie Parker informed his compositional tempo. Works like Horn Players (1983) or Now’s the Time (1985) pay tribute to this musical lineage. Jazz represented for Basquiat both Black genius and improvisational freedom — the ability to break form while still composing structure.

K – Knowledge

Basquiat was largely self-taught but ferociously intellectual. He devoured books on anatomy, African history, and philosophy, and his paintings reflect encyclopedic curiosity. His references range from Leonardo da Vinci to Henry Dreyfuss, from African masks to Greek myth. Knowledge, for Basquiat, was not elitist but democratic — scribbled on walls, layered on canvas, accessible to anyone willing to look deeper. He once said, “I cross out words so you will see them more; the fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them.”

L – Language

Words are central to Basquiat’s visual lexicon. Scrawled, repeated, or crossed out, language in his paintings operates as rhythm and code. It invokes advertising slogans, jazz lyrics, political commentary, and linguistic play. His bilingual upbringing (English, Spanish, French, Creole) infused his work with polyphonic energy — a graffiti-poetic grammar that blurs meaning and rhythm. Each word becomes a mark, and each mark a declaration.

M – Market

Basquiat’s market is one of the strongest in contemporary art. Since his untimely death in 1988, his prices have escalated from tens of thousands to tens of millions. In 2017, Untitled (1982) — a monumental skull rendered in oil stick and acrylic — sold for $110.5 million at Sotheby’s, setting a record for any American artist at auction. The market remains deep and international, spanning institutions, private foundations, and global collectors. His scarcity (roughly 600 paintings and 1,500 works on paper) ensures enduring demand.

N – Neo-Expressionism

Basquiat was often grouped with Neo-Expressionism, a movement defined by emotional intensity and figurative revival in the 1980s. Yet he resisted categorisation. Unlike his white European contemporaries, Basquiat infused expressionism with street culture, jazz, and African heritage. His frenetic energy and visual density transcended stylistic labels — creating a hybrid language that felt both ancient and futuristic.

O – Outsider Status

Basquiat was both insider and outsider. He rose from homelessness to elite galleries within a few years, yet remained alienated by the racial and economic inequalities of the art world. Critics exoticised his Afro-Caribbean heritage, often failing to grasp the intellectual complexity of his work. His outsider identity became both his brand and his burden — an artist embraced by the system he critiqued.

P – Poetry

Language in Basquiat’s art reads like visual poetry. His fragments — “THOR,” “ORO,” “SICKLE,” “TAR” — operate as lyrical riffs, each layered with meaning. Many canvases can be read as poems about power, history, and mortality. He also wrote prolifically in notebooks, filling pages with wordplay, sketches, and philosophical musings. His approach prefigured later interdisciplinary artists who blend text, image, and politics.

Q – Queens and Kings

Basquiat’s world was populated by royalty — symbolic kings, crowned saints, and historical figures elevated to divine status. His kings were not monarchs of empire but cultural warriors who defied oppression. King Alphonso (1981) and Charles the First (1982) blend references to jazz greats and medieval heraldry, asserting a lineage of Black nobility. His art crowned those history overlooked.

R – Race and Representation

Race was never incidental in Basquiat’s work. He tackled stereotypes head-on, portraying Black men as thinkers, martyrs, and champions. His paintings reinsert Black identity into Western art’s white narrative. Obnoxious Liberals (1982) and Per Capita (1981) address economic disparity and tokenism, while portraits like Glenn (1984) humanise individuality. His art prefigured contemporary discourses on representation and decolonisation.

S – Skulls and Saints

Basquiat’s recurring skulls symbolise both death and enlightenment. They are not macabre but alive — bursting with energy, expression, and colour. Often rendered as electric X-rays of the mind, these skulls connect to African masks, Christian iconography, and the memento mori tradition. Through them, Basquiat explored mortality, spirituality, and identity — themes heightened by his own awareness of fame’s fleeting nature such as in Untitled (Head).

T – Text and Symbols

From crowns and halos to arrows and logos, Basquiat’s symbols form a personal iconographic system. He borrowed from advertising, alchemy, and Afro-Caribbean folklore. Text fragments like “OPD” (Omnipotent Police Department) or “TAR” (racial slur reappropriated) function as linguistic traps — forcing the viewer to question their own assumptions. His visual language is dense yet precise, mapping the chaos of modern consciousness.

U – Untitled (1981–1983)

Basquiat produced numerous works titled Untitled, yet each is distinct. The 1982 Untitled (depicting a roaring skull) is his most famous and commercially significant. Its visceral force, monumental scale, and psychological depth encapsulate the artist’s genius. The anonymity of “Untitled” suggests universality — a refusal to be pinned down or commodified by title.

V – Versus the System

Basquiat’s art is a confrontation — against racism, capitalism, and institutional hypocrisy. He painted on discarded doors, windows, and packing crates, transforming urban detritus into cultural critique. His use of brand names like “Esso” or “Arm & Hammer” satirised consumerism, while his depictions of police brutality exposed systemic injustice decades before it became mainstream discourse.

W – Warhol

Basquiat’s friendship and collaboration with Andy Warhol marked one of the most storied partnerships in modern art. Introduced by dealer Bruno Bischofberger in 1982, they created over 100 collaborative works, merging Warhol’s silkscreen precision with Basquiat’s raw energy. Critics were divided: some saw mutual exploitation, others a symbiotic dialogue. For Basquiat, Warhol represented both mentor and mirror — a figure of fame and commodification he both emulated and resisted.

X – X-Ray Vision

Basquiat’s layered approach often resembles an X-ray — revealing rather than concealing. Figures are dissected, text exposed, meaning fragmented. His “x-ray” vision metaphorically unveils hidden histories: the skeletons of empire, colonialism, and capitalism. This transparency of form parallels his transparency of thought — painting as both autopsy and revelation.

Y – Youth

Basquiat’s career lasted barely a decade. He was 20 when he first exhibited, 22 when he achieved international fame, and just 27 when he died of a heroin overdose in 1988. His youth was both his fuel and his tragedy. Yet the brevity of his life only amplifies the intensity of his output — an extraordinary body of work that continues to speak to the urgency of being young, brilliant, and misunderstood.

Z – Zeitgeist

More than an artist, Basquiat became the embodiment of an era — the 1980s zeitgeist of cultural fusion, racial awakening, and downtown rebellion. His art captured the spirit of New York’s raw creativity before gentrification, a time when walls were canvases and collaboration was currency. Today, his legacy transcends art history: he is a global symbol of creative freedom, Black excellence, and defiant individuality.

The Legacy of the Crown

Basquiat’s life may have been short, but his influence is limitless. His paintings, once dismissed as graffiti, now hang in the world’s most prestigious institutions — MoMA, the Whitney, Tate Modern, Fondation Louis Vuitton. His visual lexicon — crowns, masks, skulls, text — continues to inspire artists, designers, and musicians.

For collectors, Basquiat represents both cultural capital and historical permanence: a once-in-a-generation figure who fused intellect and instinct, politics and poetry, life and death. To collect Basquiat is not merely to own a painting — it is to hold a fragment of the modern condition, a crown forged from chaos.

Read more Basquiat content in our Basquiat Collector's Guide, The Meaning Behind Basquiat's Symbols and The Most Expensive Basquiat artworks.

Discover original Basquiat art for sale and contact our galleries via info@guyhepner.com for latest availabilities.