Few series in contemporary art have captured the psychological tension of modern life as vividly as Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities. Conceived between 1978 and 1983, these monumental black-and-white drawings of sharply dressed figures twisting, falling, and convulsing in midair remain some of the most enduring and instantly recognizable images of the late twentieth century. The series cemented Longo’s place within the Pictures Generation - a group of artists who, emerging in New York in the late 1970s, interrogated the influence of photography, cinema, and mass media on perception and identity.

Longo developed Men in the Cities at a moment when painting was giving way to new visual languages - photography, film, and postmodern appropriation. Working in New York after studying in Buffalo and co-founding the Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center alongside Cindy Sherman, Longo was fascinated by how mediated images shaped emotion.

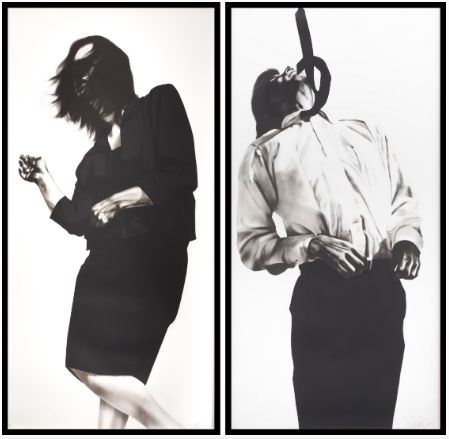

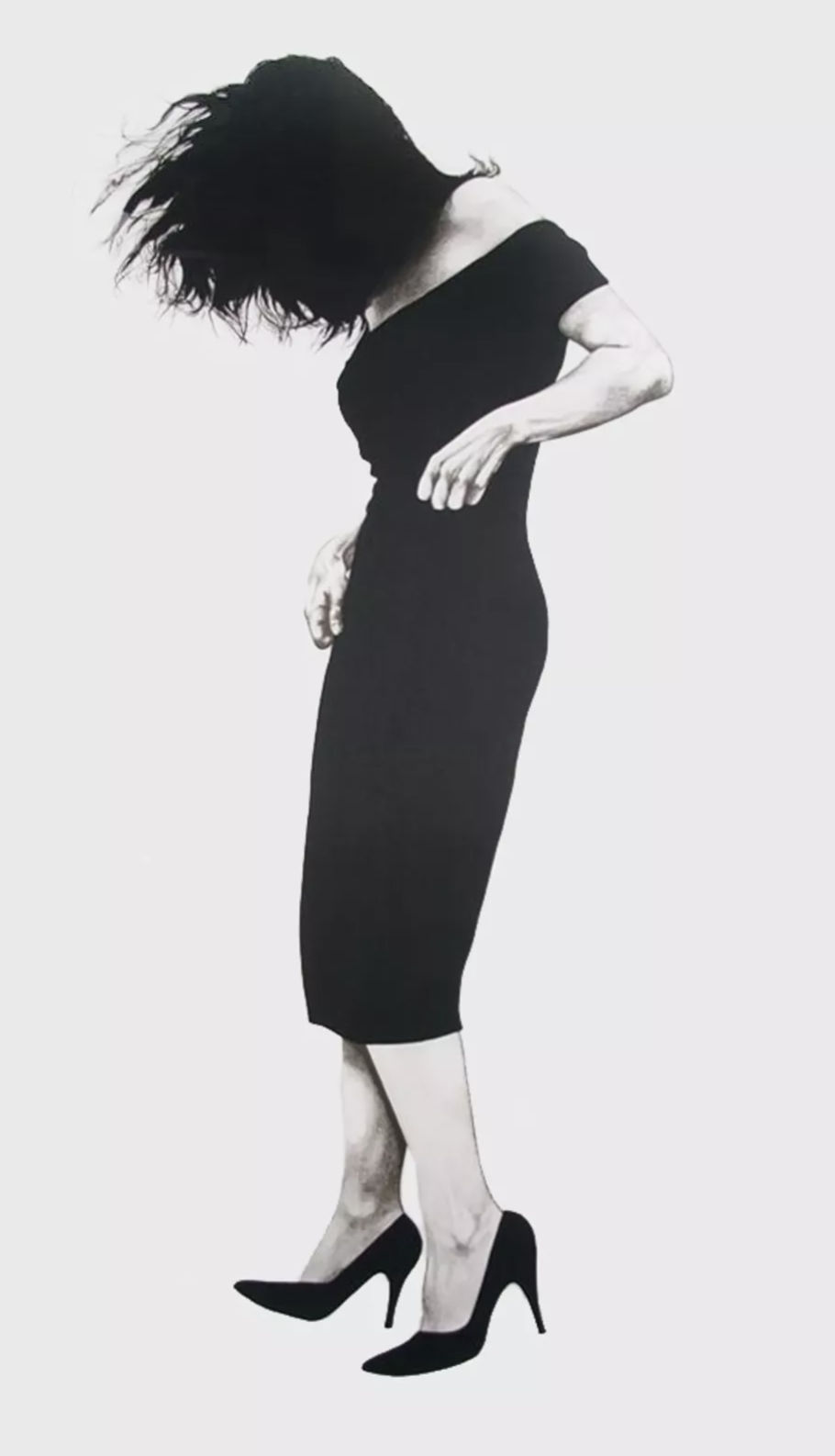

The genesis of the series was performative. On a rooftop in Manhattan, Longo photographed friends and peers dressed in business attire. To provoke authentic, uncontrolled movement, he startled them - throwing objects, blasting music, or tugging ropes - capturing the instant their bodies lost composure. These photographs, shot against the skyline, became the basis for his large-scale drawings rendered in charcoal and graphite with almost photographic precision.

The resulting images - figures isolated against stark white backgrounds, frozen mid-motion - distill a single instant of psychological rupture. The anonymity of the subjects, combined with their formal suits and dresses, turns each into an archetype of late capitalist anxiety: the elegant professional under invisible pressure, suspended between power and collapse.

The Men in the Cities series resonated immediately with a generation navigating the contradictions of urban life: ambition and alienation, control and breakdown. Critics hailed the work as both cinematic and sculptural - its large scale giving the figures a monumental gravitas, while their weightless gestures suggested fragility.

In its visual language, Longo’s series bridged multiple traditions: the chiaroscuro of Renaissance drawing, the movement studies of photography pioneers like Muybridge, and the emotional austerity of Minimalism. Yet the work’s content was unmistakably of its time - an embodiment of 1980s New York, where corporate ambition, mass media, and urban isolation collided.

Longo’s figures became icons of modern disquiet. Their gestures - graceful, convulsive, ambiguous - seemed to reflect the psychic toll of life lived in constant performance. As Longo once noted, the figures “look like they’re dancing, but they’re actually falling.” That duality - beauty entwined with violence, control with surrender - is the philosophical heart of the series.

Born in Brooklyn in 1953, Longo came of age in a cultural moment of political turbulence and artistic reinvention. After studying sculpture in Buffalo, he co-founded Hallwalls, an artist-run space that championed experimental practices and became a hub for the emerging Pictures Generation. In New York, Longo’s circle included artists like Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, and Laurie Simmons - creators who redefined art as a space for critiquing media, gender, and representation.

Though Men in the Cities remains his most famous body of work, Longo’s practice spans sculpture, film, photography, and monumental charcoal drawings. His later works - large-scale renderings of waves, bullets, and political imagery - continue his exploration of power and spectacle, confronting viewers with both awe and unease.

Over four decades after their creation, works from Men in the Cities continue to command strong demand on the global market. Original drawings are held in major public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, while editioned lithographs - such as Gretchen & Eric (1985) and Cindy & Max (1981) - are highly sought after by collectors.

The appeal lies in the series’ perfect balance of accessibility and sophistication. Each work is instantly recognizable yet endlessly interpretable. At auction, prints regularly outperform estimates, with recent sales fetching upwards of six figures - Gretchen, from Men in the Cities achieving $176,400 at Christie’s in 2025, far above its estimate. The steady market activity for both unique and editioned works attests to the series’ enduring resonance and blue-chip status.

Collectors are drawn not only to the work’s graphic precision and emotional charge, but also to its cultural ubiquity. The imagery has become a shorthand for late twentieth-century aesthetics - at once cool, cynical, and deeply human.

Perhaps no moment cemented Men in the Cities more firmly in public consciousness than its appearance in Mary Harron’s film American Psycho (2000). Hanging in the pristine white apartment of Patrick Bateman, the series’ twisting figures serve as psychological mirrors of the protagonist - a Wall Street banker whose obsession with perfection conceals moral and emotional decay.

The choice was deliberate: the works’ crisp surfaces and contorted bodies encapsulate the paradox at the film’s core - surface order masking inner violence. Bateman’s life, like Longo’s figures, is a study in aestheticized collapse. The inclusion of Men in the Cities transformed the series from an art-world emblem into a pop-cultural icon, a symbol of modern alienation and performative civility.

Beyond cinema, Longo’s imagery has influenced fashion, music videos, and advertising. The stark silhouette of a body in motion - suspended between grace and chaos - continues to reverberate through visual culture, from editorial photography to streetwear design.

The sustained interest in Men in the Cities stems from its timeless tension. It captures something universally human: the struggle to maintain composure under invisible pressures. Longo’s figures are not victims or heroes - they are us, caught mid-fall between beauty and breakdown.

In today’s world, where the boundaries between image, performance, and identity blur more than ever, the series feels newly relevant. Its minimalist clarity and psychological depth continue to attract collectors and institutions alike, ensuring its place as one of the defining visual statements of contemporary art.

Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities endures because it fuses formal mastery with emotional truth. Its figures - impeccably dressed, violently suspended, existentially alone - embody the contradictions of modern life: the elegance of appearances, the chaos beneath, the beauty of control giving way to collapse.

Historically, it anchors Longo within the lineage of artists who turned the image into critique. Economically, it remains one of the most stable and coveted series in the contemporary market. Culturally, it continues to haunt the collective imagination - from museum walls to Hollywood screens - reminding us that every polished façade conceals a moment just before the fall.

For more information on Robert Longo's artwork, please email info@guyhepner.com.