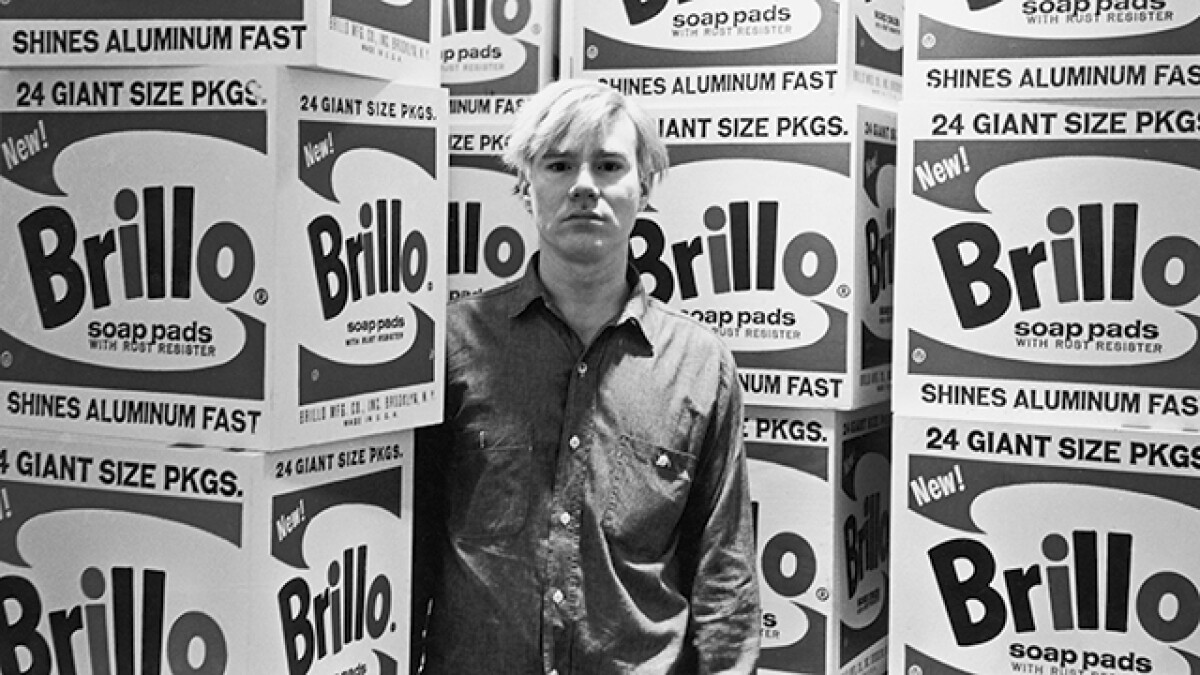

Few works in 20th-century art have provoked as much debate, fascination, and philosophical inquiry as Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes. First exhibited in 1964 at New York’s Stable Gallery, these wooden replicas of commercial soap-pad packaging transformed an everyday supermarket product into one of the most discussed objects in the history of modern art. The Brillo Boxes mark the culmination of Warhol’s exploration of consumer culture, mass production, and the blurred line between the art object and the commodity. They also prefigure much of what would later define conceptual art: the idea that the concept behind a work could be more important than its physical form.

Warhol’s Brillo Boxes stand as a key turning point not only in his own career but also in the trajectory of postwar art. To understand their impact, it’s necessary to trace how they emerged from Warhol’s fascination with commercial imagery, how they connected to his earlier series like the Campbell’s Soup Cans, and how their presentation — in the form of a simulated supermarket installation — questioned the very definition of what art could be.

From the Supermarket to the Gallery: Origins of the Brillo Boxes

By 1964, Warhol had already become synonymous with the imagery of consumer America. His Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), Coca-Cola Bottles, and Marilyn Diptych had established him as the leading figure of Pop Art — an artist unafraid to draw from mass media, advertising, and popular culture. While many of his contemporaries, such as Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist, were reinterpreting commercial imagery with painterly irony or satirical distance, Warhol approached it with an almost mechanical detachment. He wanted to “be a machine,” as he famously said, reflecting the industrial processes that defined postwar America.

The Brillo Boxes emerged directly from this interest in mechanisation and replication. Rather than painting or silkscreening commercial imagery onto canvas, Warhol decided to reproduce three-dimensional supermarket packaging itself. Working with carpenter Gerard Malanga and a team of studio assistants at his legendary studio, The Factory, Warhol created hundreds of wooden boxes that precisely mimicked the design of household cleaning products like Brillo, Heinz Ketchup, Del Monte Peaches, and Campbell’s Tomato Juice.

Each box was meticulously crafted to the same dimensions as its cardboard supermarket counterpart. The designs were hand-silkscreened onto the surfaces, maintaining the flat, graphic precision of the originals. The result was uncanny: from a distance, the boxes looked identical to those one might find stacked in a grocery store warehouse. But up close, they were revealed as art objects — solid, painted, and deliberately non-functional.

This decision to reproduce, rather than represent, was revolutionary. Where the Campbell’s Soup Cans had transformed a two-dimensional advertising image into painting, the Brillo Boxes extended that gesture into the realm of sculpture. Warhol didn’t just depict consumer goods; he became the factory producing them.

The “Supermarket” Installation: Stable Gallery, 1964

The first public showing of the Brillo Boxes at the Stable Gallery in 1964 was itself an act of conceptual theatre. Rather than spacing the works apart as traditional sculptures, Warhol and gallerist Eleanor Ward installed them in stacks that mimicked a warehouse or a supermarket stockroom. Viewers entering the gallery were confronted not with the aura of “fine art,” but with an environment that felt industrial and commercial.

Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, Heinz Boxes, and Campbell’s Tomato Juice Boxes filled the gallery floor, creating an immersive landscape of repetition. There were no pedestals, labels, or visual cues separating “art” from “product.” The presentation was, as critic Arthur Danto later noted, almost indistinguishable from what one might see in a supermarket.

The effect was shocking. Many visitors were bewildered, even outraged. For some, the exhibition seemed to mock the seriousness of art itself. Why would anyone pay gallery prices for an object identical to one that could be bought for pennies at a grocery store? Others saw it as a bold statement about the merging of art and commerce — an embrace of the consumer reality of postwar America rather than a rejection of it.

Warhol himself remained characteristically opaque about his intentions. When asked why he made the boxes, he famously replied, “I just paint things I always thought were beautiful, things you use every day and never think about.” To Warhol, the Brillo box — bright, clean, repetitive — embodied the aesthetics of modern life.

Critical Reaction: Outrage, Confusion, and the Birth of Conceptual Debate

The reception of the Brillo Boxes in 1964 was polarized. Many critics dismissed the works as a cynical provocation. Conservative reviewers saw them as a symptom of art’s moral decline, accusing Warhol of mere imitation and calling the exhibition “a hoax.” Even some within the avant-garde questioned whether such an unaltered commercial form could be called art.

Yet others recognized the conceptual leap Warhol had made. The philosopher Arthur C. Danto, visiting the exhibition by chance, later wrote that the Brillo Boxes transformed his understanding of art. Danto argued that Warhol’s boxes forced viewers to confront the difference between an ordinary object and an art object. The two were visually identical — a Brillo box in a gallery and one in a supermarket — yet they carried vastly different meanings depending on their context.

For Danto, this distinction was revolutionary: it wasn’t the appearance of the object that made it art, but the idea behind it — the decision to present it within the framework of art. His later essay, The Artworld (1964), would become a cornerstone of contemporary art theory, proposing that an object becomes art through the interpretive context and institutional structures that surround it.

In this sense, Warhol’s Brillo Boxes anticipated the conceptual and minimalist movements that would define the late 1960s and 1970s. Artists such as Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, and later Jeff Koons would follow in Warhol’s footsteps, exploring seriality, industrial materials, and the commodification of art. But it was Warhol who first collapsed the boundary between the art object and the consumer object so completely.

From Soup Cans to Brillo Boxes: Mechanisation, Repetition, and the Logic of Capital

The Brillo Boxes cannot be fully understood without looking back to Warhol’s earlier works — particularly the Campbell’s Soup Cans of 1962. The Soup Cans were a revelation when first shown at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. Displayed in rows like supermarket shelves, each canvas depicted a different variety of Campbell’s soup, from Tomato to Chicken Noodle. The series played on the tension between sameness and difference, repetition and uniqueness — themes that would reach their logical extreme in the Brillo Boxes.

In both works, Warhol mimicked the visual language of consumer capitalism. But whereas the Soup Cans remained tied to the history of painting — the artist’s hand, the canvas, the wall — the Brillo Boxes moved fully into the industrial realm. They were literally “factory-made” in process and concept, embodying Warhol’s mantra of “business as art.”

Warhol’s mechanical silkscreen technique reinforced this idea of industrial production. Just as Campbell’s manufactured soup and Brillo produced soap pads, Warhol’s studio became a factory of images — churning out portraits, prints, and boxes with assembly-line efficiency. By removing the trace of the artist’s hand, Warhol elevated the aesthetics of uniformity and questioned traditional notions of artistic originality.

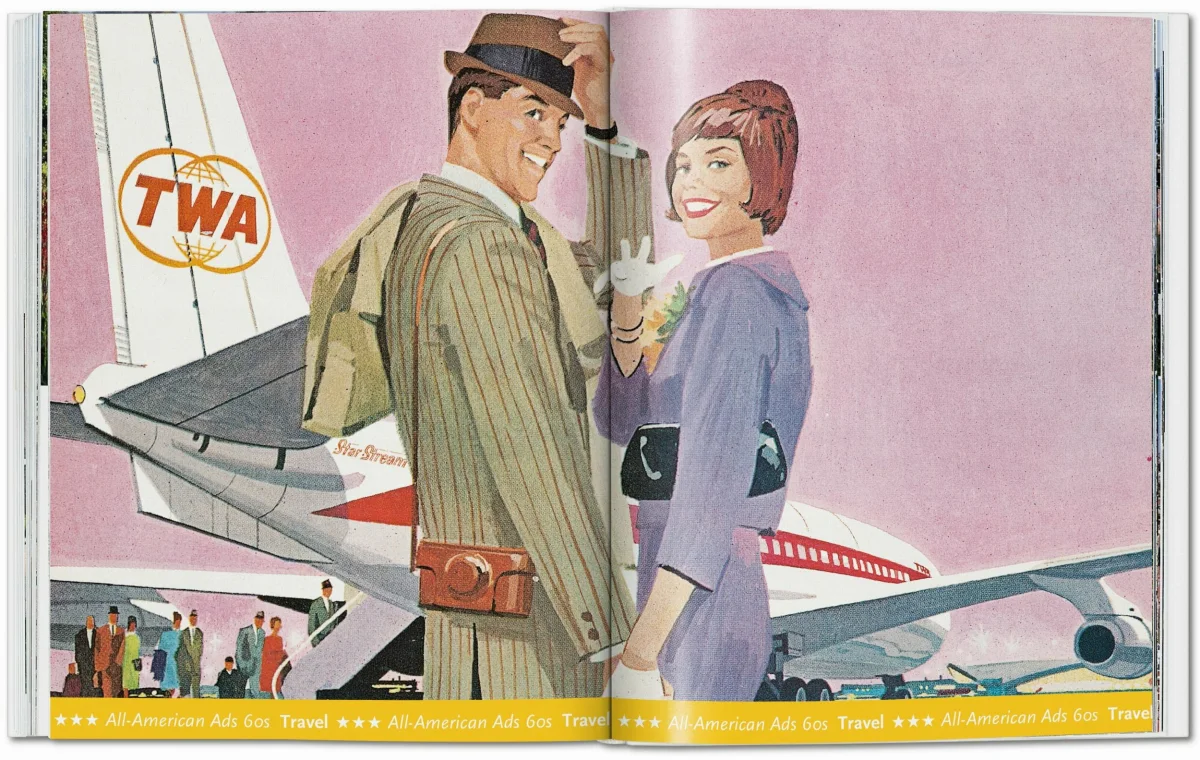

This move also reflected the broader cultural context of 1960s America. The postwar economic boom had transformed the United States into a society of mass consumption. Supermarkets, advertising, and television defined the visual environment of everyday life. Warhol’s art didn’t critique this world from the outside — it mirrored it from within. By reproducing its icons without irony, Warhol held up a mirror to the collective desires, anxieties, and repetitions of modern consumerism.

The Philosophy Behind the Box: Authorship, Authenticity, and the Aura

The Brillo Boxes also raise profound questions about authorship and authenticity. If an art object can be indistinguishable from a mass-produced product, what makes it “authentic”? Is it the artist’s hand, the signature, the context, or the idea?

Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction argued that technological reproduction diminishes the “aura” — the unique presence — of an artwork. Warhol’s Brillo Boxes invert this logic: they create aura through replication. The boxes’ very sameness becomes the source of their fascination. Each is technically identical, yet as art, each carries value, rarity, and status that the supermarket box does not.

This paradox is central to Warhol’s practice. His works repeatedly oscillate between the industrial and the sacred, the mass-produced and the exclusive. In doing so, they reveal the mechanisms through which value is constructed in both art and commerce. The Brillo Boxes are, in a sense, the purest expression of Warhol’s belief that art and business are not opposites but mirror systems.

The Box as Symbol: Packaging, Identity, and the Surface of Modern Life

Packaging fascinated Warhol. As a former commercial illustrator, he understood the power of design to seduce and communicate. The Brillo box — bold red and blue typography on a white background — was not merely functional packaging; it was visual culture distilled to its essence.

In transforming packaging into sculpture, Warhol captured the modern condition of surface and branding. In the world of mass consumption, the box — the wrapper — becomes as important as the product inside. The Brillo Boxes are thus not about soap pads, but about the packaging of experience itself. They symbolize a culture in which identity, value, and desire are mediated through commercial design.

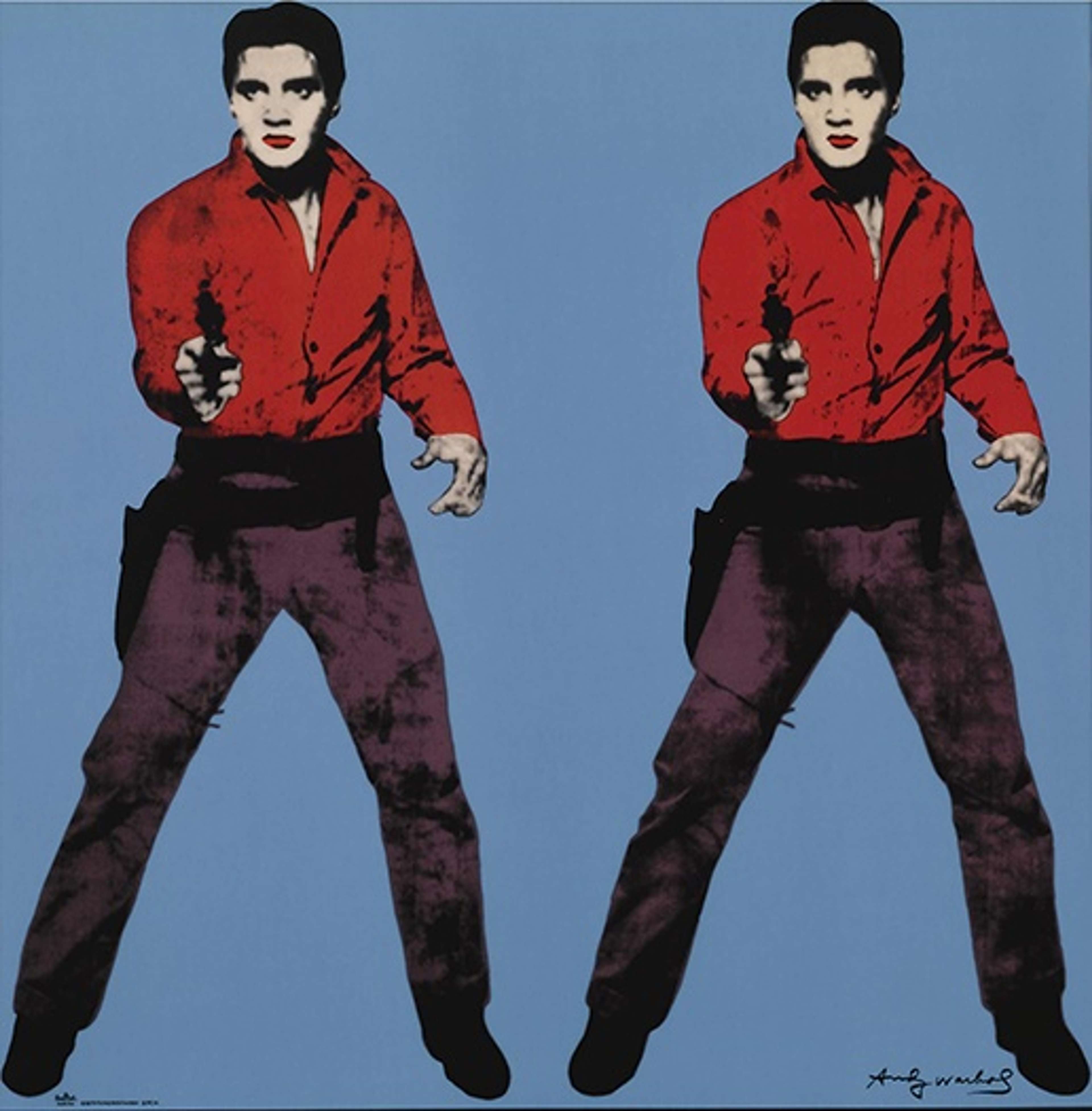

This theme resonates across Warhol’s oeuvre. His Marilyns and Elvises are also “packaged” icons — celebrity images reproduced until they lose individuality. In both cases, repetition erases meaning while simultaneously creating it anew. The Brillo Boxes apply this logic to the inanimate world of products, suggesting that our relationship to things is no less constructed than our relationship to people.

Legacy and Influence: From Minimalism to Postmodernism

The impact of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes was immediate and far-reaching. Minimalist artists like Donald Judd and Robert Morris, who were developing their own box-like sculptures at the same time, recognized in Warhol’s work a radical extension of their concerns. But whereas Judd’s boxes were abstract and self-referential, Warhol’s were loaded with cultural meaning — brand, commerce, and everyday life.

In the 1980s and beyond, artists such as Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, and Damien Hirst would inherit Warhol’s dialogue between art and commodity. Koons’s New Hoover Deluxe Shampoo Polishers and Balloon Dogs owe a clear debt to Warhol’s strategy of elevation through display — taking consumer objects and recontextualizing them as luxury art. Similarly, Hirst’s pharmaceutical cabinets, filled with neatly arranged boxes of medicine, echo the serial presentation and clinical aesthetic of Warhol’s supermarket installations.

Art historians also see the Brillo Boxes as a precursor to the conceptual art of Joseph Kosuth and Sol LeWitt. Kosuth’s 1965 work One and Three Chairs — which presents a chair, a photograph of it, and a dictionary definition — directly engages with the same philosophical question that Danto identified in Warhol: how identical appearances can hold radically different meanings depending on context.

In this way, the Brillo Boxes bridge Pop and Conceptual art, uniting visual seduction with intellectual provocation. They are both image and idea, surface and theory.

Market and Museum: The Value of the Box

Ironically, the Brillo Boxes that once mocked the commodification of art have themselves become highly valuable commodities. Original 1964 examples now reside in major museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, Tate Modern, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, and command millions of dollars at auction. Their proliferation — both as artworks and as symbols — mirrors the very logic of consumerism they embody.

Warhol himself continued to revisit the motif throughout his career. Later versions of the Brillo Boxes, produced in the 1970s and 1980s, introduced variations in color and finish — including silver, pink, and gold editions — further blurring the line between fine art and merchandise. These later works transformed the Brillo Box into a Pop icon in its own right, as recognizable as the Marilyns or Soup Cans.

The irony is not lost: a work that questioned the value of art in an age of reproduction has become a blue-chip collectible, endlessly reproduced in art books, museum gift shops, and even as miniature replicas. Yet perhaps this is precisely the point. The Brillo Boxes are self-fulfilling prophecies — artworks that reveal how culture turns everything, including critique, into commodity.

The Box That Changed Everything

Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes remain among the most important and debated works of modern art. Their power lies not in craftsmanship or material innovation but in conceptual audacity. By taking a mundane supermarket object and declaring it art, Warhol dismantled the traditional hierarchies that separated “high” art from mass culture.

In doing so, he anticipated the philosophical questions that would dominate the art world for decades: What defines art? Who decides? Where does meaning reside — in the object, the artist, or the audience? The Brillo Boxes offered no clear answers, only the provocation of their presence.

Looking back, it’s easy to see why the Brillo Boxes caused such an uproar. They seemed to erase the difference between the gallery and the grocery store, between originality and replication, between art and business. Yet it was precisely this erasure that made them revolutionary. Warhol’s boxes reflected a world in which images, products, and people were all mass-produced, packaged, and consumed.

More than half a century later, their relevance has only deepened. In an era of digital duplication, brand identity, and influencer culture, Warhol’s insight feels prophetic: that the boundaries between art, commerce, and everyday life are not barriers but mirrors.

The Brillo Boxes stand as both parody and prophecy — a Pop masterpiece that continues to challenge our assumptions about creativity, authenticity, and the world of things. In the end, Warhol’s supermarket wasn’t just a gallery installation; it was a vision of the future — one in which art, like soap pads, would be endlessly replicated, distributed, and consumed.

Discover Andy Warhol original art for sale and contact our galleries via info@guyhepner.com for latest availabilities,