Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings are often recognized instantly — the crisp comic-book dots, the bold primary colors, the stylized emotions frozen mid-gesture. Yet beneath their cool, graphic precision lies an intense narrative intelligence. Lichtenstein was not merely appropriating imagery from popular culture; he was distilling stories to their most potent, economical forms. Like a playwright following the classical unities of action, time, and place, he created images that capture the total drama of a scene in one immaculate frame. His art reminds us that storytelling doesn’t always need motion or sequence — sometimes, a single moment can hold an entire universe of tension, irony, and meaning.

Early Life and the Path to Pop

Roy Lichtenstein was born in New York City in 1923. Raised in an upper-middle-class Manhattan family, he showed an early interest in drawing, model-making, and jazz. He attended the Art Students League while still in high school, studying briefly with Reginald Marsh before enrolling at Ohio State University in 1940. His early education emphasized both studio practice and art theory — an unusual combination that later shaped his analytical approach to making art about images themselves.

Lichtenstein’s studies were interrupted by World War II, during which he served in the U.S. Army. After the war, he returned to Ohio State to complete his degree and teach there. Throughout the 1940s and ’50s, he experimented with different styles — from Cubist still lifes to semi-abstract figures influenced by Picasso and Klee. His early work was competent but derivative, the sort of searching experimentation common among young artists in the shadow of Abstract Expressionism. The mature Lichtenstein — the cool formalist with comic-book characters and mechanical dots — was still some years away.

Breaking with Abstraction

By the late 1950s, the Abstract Expressionists dominated the New York art scene. Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline had made painting a field of heroic gesture, personal revelation, and existential risk. Lichtenstein admired their energy but also recognized their vulnerability to parody. In the early 1960s, he began to experiment with imagery from popular culture — Mickey Mouse, bubble-gum wrappers, comic strips — treating them with the same large scale and painterly seriousness that the Abstract Expressionists reserved for their inner emotions. The shift was radical, even mischievous.

His 1961 painting Look Mickey is often cited as the turning point. Adapted from a children’s comic book, the work features Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse rendered in flat, mechanical color, outlined in thick black lines, and punctuated by Ben-Day dots. It was both painting and quotation — an image about the act of looking at images. By elevating low-brow cartoon material into the realm of fine art, Lichtenstein questioned the hierarchy between “high” and “mass” culture. The painting was also humorous and self-aware: Mickey laughs while Donald, who thinks he has caught a fish, realizes he’s hooked his own jacket — a sly metaphor for the artist’s own act of self-entrapment in the image.

The First Shows and the Shock of Pop

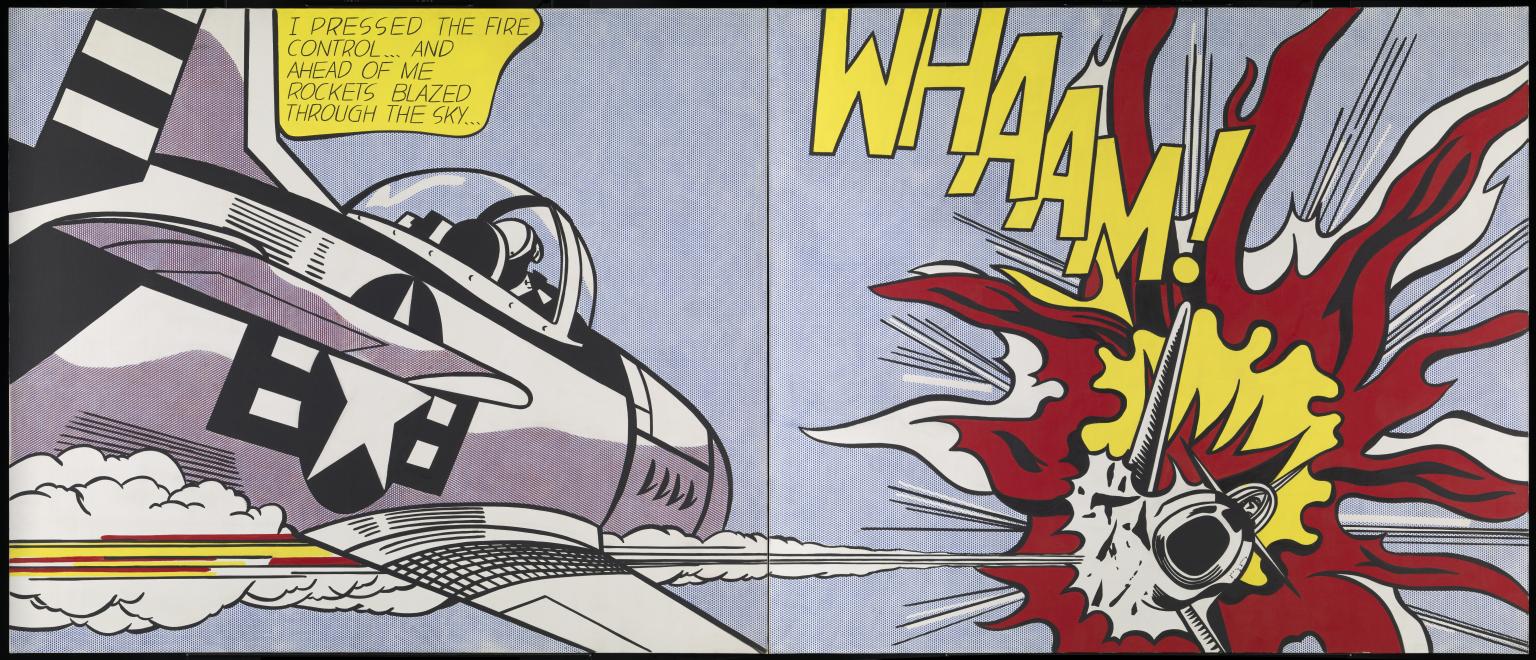

Lichtenstein’s breakthrough came in 1962, when the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York exhibited his first solo show of comic-inspired paintings. It sold out before the opening. Works such as Whaam!, Drowning Girl, and Blam! turned pulp war comics and romance strips into monumental canvases. Viewers were stunned by the combination of commercial imagery and painterly rigor. The art world, divided between excitement and outrage, immediately took notice.

Critics like Max Kozloff and Hilton Kramer accused Lichtenstein of plagiarism, arguing that he simply copied panels from comic books without originality. Others, like Lawrence Alloway and Barbara Rose, recognized the conceptual sophistication in his approach — that his art was not about copying, but about mediation, about how mass culture compresses narrative and emotion into standardized symbols. Lichtenstein himself wryly remarked, “I’m not interested in the subject matter, and I’m not trying to make a comment on it. I’m interested in the way it’s composed.”

The debate around authenticity versus appropriation would become central to Pop Art. Yet, for all its irony, Lichtenstein’s work was deeply serious in its structural discipline. He was less a provocateur than a formalist, using the language of comics to explore composition, color, and the tension between mechanical reproduction and human emotion.

The Art of the Single Frame

Lichtenstein’s paintings are essentially frozen stories. Like frames from an unseen film, they imply both before and after — a moment chosen for its perfect dramatic equilibrium. This narrative compression aligns, almost unconsciously, with the classical Greek unities of action, time, and place. In ancient drama, these unities created focus and intensity: one story, in one location, over one period. Lichtenstein achieves a similar effect visually. Every painting is a self-contained stage; every figure, a protagonist caught mid-gesture.

In Drowning Girl, for instance, the heroine floats in stylized waves, her thought bubble reading, “I don’t care! I’d rather sink than call Brad for help!” The scene is static — she neither drowns nor swims — yet within that stillness lies an entire melodrama of pride, heartbreak, and irony. Lichtenstein’s framing is ruthless: everything extraneous is cut away. The viewer reads it like a cinematic close-up, an emotional crescendo without context.

This ability to create narrative through isolation is what makes his work so enduring. Each painting is both image and story, both symbol and sentence. The cropping, the flat color fields, the mechanical dots — all contribute to an aesthetic of precision and containment. The “picture-perfect vignette” becomes a storytelling device, allowing viewers to project their own continuities into the gaps he leaves open.

Beyond the Comics: Expanding the Language of Pop

While Lichtenstein’s comic-book paintings made him famous, they were only one chapter in a long and varied career. By the late 1960s, he began exploring art-historical themes — still lifes, brushstrokes, mirrors, and even reinterpretations of Monet’s Cathedrals. These series demonstrated his ongoing fascination with how images signify and how styles carry meaning.

His Brushstrokes paintings of the mid-’60s, for example, parody the very language of Abstract Expressionism. He transforms the spontaneous gesture — the mark of authenticity and emotion — into a controlled, mechanical sign. The irony is exquisite: a painting of a brushstroke, meticulously rendered by hand, mimicking the appearance of mass production. The artist becomes both commentator and craftsman, exposing how even “expression” can be codified and reproduced.

Later works, such as his Interiors series of the 1990s, further refined this narrative stillness. These paintings depict empty modern rooms filled with stylized furniture, artworks, and sunlight. The human presence is implied but absent — another kind of story told through omission. They read like cinematic establishing shots, serene yet uncanny, inviting the viewer to imagine who has just left or is about to enter.

Critical Reception and the Question of Irony

From the beginning, critics were divided. Some dismissed Lichtenstein as cold and mechanical, a painter without soul. Others recognized his precision as a new kind of lyricism — a poetry of form and distance. Over time, his reputation grew as scholars and viewers began to understand his work as a meditation on perception and communication. He was, in effect, painting about how modern people see and feel through mediated images.

Rosalind Krauss and Michael Fried, among others, later situated his work within the broader postmodern discourse on simulacra and reproduction. Yet Lichtenstein never lost sight of the visual pleasure of painting itself. His dots may mimic printing, but each one is hand-painted. The cool surface hides a meticulous craft. “The closer you get,” he once said, “the more the dots dissolve into abstraction. Step back, and it’s a girl crying.” This duality — between distance and intimacy, emotion and artifice — is what makes his work so compelling.

Legacy and Influence

By the time of his death in 1997, Roy Lichtenstein had long been recognized as one of the central figures of 20th-century art. His influence extends far beyond Pop Art, shaping generations of painters, graphic designers, filmmakers, and digital artists who use the language of mass media as their own. The clarity of his imagery — that distilled, narrative charge — prefigures today’s Instagram culture of visual snippets and compressed storytelling.

Museums around the world continue to celebrate his achievements. Major retrospectives at the Guggenheim (1993), the Art Institute of Chicago (2012), and Tate Modern (2013) have reaffirmed his place in art history. His market, too, reflects enduring relevance: key works regularly command tens of millions at auction, and his prints remain among the most collected of all post-war artists.

Lichtenstein’s disciplined visual storytelling also influenced contemporary painters such as Julian Opie, as well as filmmakers like Wes Anderson, whose symmetrical frames and self-contained worlds echo the artist’s sense of compositional harmony. Even in advertising and pop culture, his vocabulary — the bold speech bubble, the comic-frame crop — has become shorthand for irony and emotion.

Storytelling in Stillness

What ultimately distinguishes Roy Lichtenstein is his ability to make stillness dramatic. His paintings are visual paradoxes: static yet dynamic, impersonal yet intimate. They function as moments suspended between action and inaction, like a freeze-frame from a film that somehow contains the whole story. In this respect, they recall the theatrical unity of classical drama — one action, one place, one time — yet transposed into the language of the modern image.

Every Lichtenstein painting is a stage. The protagonists are caught in the instant before something happens or just after it has passed. The viewer is left to bridge the gap — to imagine the scene’s beginning and end. This participatory storytelling makes his art endlessly fresh. We project ourselves into his still frames, filling them with our own anxieties and fantasies.

In Whaam!, the explosion from a fighter plane is both literal and psychological — a symbol of the violence embedded in spectacle. In In the Car, the woman’s tense profile and the man’s fixed gaze suggest a drama of unspoken resentment. Even in later works like Room with Mirrored Wall, the empty interiors shimmer with unseen presence. In every case, Lichtenstein achieves what the greatest storytellers achieve: he gives us just enough to imagine the rest.

The Perfection of the Moment

Lichtenstein once said that he wanted his paintings to look “as if they were programmed,” but behind that precision lies a deep humanism. His works remind us that emotion can be formal, that clarity can be expressive, and that narrative can exist in a single glance. The beauty of his art lies in its equilibrium — the balance between control and chaos, surface and depth, irony and sincerity.

If Andy Warhol was Pop’s philosopher of repetition and fame, Lichtenstein was its dramatist — orchestrating the visual language of modern life into picture-perfect vignettes. He translated the rush of media into moments of pure stillness, where time stops and emotion crystallizes. Through these deceptively simple compositions, he proved that the grand tradition of storytelling could survive in the age of the printed image.

More than half a century later, his paintings remain as sharp, poignant, and mysterious as ever — windows into that strange modern condition where every feeling, every story, must fit inside a frame. Roy Lichtenstein showed us that art could be both cool and sincere, both mechanical and moving. He taught us how to read pictures not just as images, but as moments of suspended life — perfect, poised, and forever unfolding.

Discover Roy Lichtenstein signed prints for sale and contact our galleries via info@guyhepner.com for more information and to speak to our teams.