Few contemporary artists have engaged with color as consistently and as inventively as David Hockney. Across six decades, Hockney has explored color as both a formal problem and a source of delight, never content to treat it merely as a descriptive tool but always as an expressive force. His commitment to color is apparent across every medium he has embraced—painting, photography, stage design, printmaking, and, most recently, digital technology. It is in his print output, however, that Hockney’s mastery of color emerges with particular clarity.

From the bold lithographs of the 1960s, through the dynamic Moving Focus series of the 1980s, to the luminous iPad drawings of the 2010s, Hockney has consistently redefined the role of color in contemporary art. For Hockney, color is not merely an adjunct to form but a means of shaping perception itself. His prints often demonstrate how color can construct space, suggest temporality, and communicate the heightened experience of looking. This essay will explore Hockney’s use of color across three distinct bodies of work—his prints more generally, the Moving Focus series, and his iPad works—demonstrating how his chromatic vision has continually expanded the possibilities of art.

Color as an Expressive Language

Hockney’s approach to color cannot be separated from his conviction that art should intensify perception. He once remarked that “we see with memory,” suggesting that vision is never a neutral record of the world but always shaped by experience and imagination. color, for Hockney, becomes the key mechanism by which this transformation occurs. His palette has often been described as “unnatural” or “exaggerated,” but such terms miss the point. His colors are truthful not to external reality but to the experience of seeing: the shock of sunlight reflected on water, the sudden blaze of flowers in bloom, or the gentle diffusion of light at dawn.

This is why his landscapes, portraits, and prints rarely confine themselves to naturalistic tones. Instead, Hockney places emerald greens beside fuchsia pinks, cobalt blues against glowing oranges, or scarlets in dialogue with lemon yellows. Such choices are not arbitrary but are carefully calibrated to evoke sensation, mood, and rhythm. In this sense, Hockney shares something with the great colorists of modernism, such as Henri Matisse, whose saturated hues were designed to communicate pleasure and intensity. Yet Hockney’s colors differ from Matisse’s in their rootedness in observation: he always begins with the act of looking, however much color then bends and amplifies reality.

The Printmaking Tradition and the Liberation of Color

Hockney has been an assiduous printmaker since the early 1960s, experimenting with etching, lithography, aquatint, and photo-collage. The medium of printmaking, with its technical demands and potential for repetition, may seem at odds with the vibrancy of his palette, but for Hockney it offered an arena in which color could be both explored and extended.

The act of layering inks in printmaking forces the artist to consider color structurally. Each decision carries consequences for depth, tonality, and harmony. Hockney seized upon this challenge, producing works that often appear as fresh and spontaneous as paintings, yet underpinned by the discipline of technical experimentation. For instance, his lithographs of swimming pools, created in Los Angeles in the 1970s, are saturated with dazzling blues that both evoke water and exceed its naturalism. The shimmering turquoise planes do not merely describe swimming pools but invite the viewer into a heightened perception of sun, light, and leisure—an image of modern Californian life bathed in color’s exuberance.

Making a Splash: Swimming Pools

Pool Made with Paper and Blue Ink for Book of Paper Pools is a vivid example of David Hockney’s ongoing fascination with the motif of the swimming pool, a subject that became central to his practice during his years in California. Here, Hockney captures the dynamic play of light, water, and reflection with an economy of line and an intensity of color that demonstrates his mastery of chromatic expression.

The surface of the pool is rendered in electric blues, layered with darker rhythmic marks that suggest the constant motion of water. The geometry of the tiled grid beneath is partially visible, reminding the viewer of depth and structure beneath the shimmering surface. Against this aquatic expanse, a sharp contrast emerges in the bold bands of red, white, and green along the pool’s edge—an assertive chromatic counterpoint that animates the composition and lends it a sense of vitality.

This interplay of saturated tones is emblematic of Hockney’s approach to color: he never uses it passively but always to heighten perception and transform the everyday into a heightened visual experience. Just as in his iconic Los Angeles pool paintings, Hockney demonstrates here how color can evoke the sensation of light itself, translating the ephemeral qualities of reflection, transparency, and depth into a fixed yet vibrant image.

Placed in the broader context of his oeuvre, Pool Made with Paper and Blue Ink for Book of Paper Pools underscores Hockney’s reputation as one of the great colorists of the modern era. His pools are not only studies of leisure and modern living but also experiments in how color and line can capture the fleeting, ever-changing effects of light on water. The radiant blues and contrasting accents here show how Hockney used color to distil an entire atmosphere into an image, turning a familiar subject into an enduring meditation on perception.

The Moving Focus Series: Color in Flux

Perhaps nowhere in his printmaking does Hockney’s chromatic imagination appear more radically than in the Moving Focus series of the 1980s. Produced in collaboration with master printer Ken Tyler, this body of work represents a major turning point in Hockney’s art, signalling a departure from naturalistic representation toward a dynamic exploration of perspective and perception.

Influenced by his engagement with Cubism, Hockney sought to overcome the fixed viewpoint of Western perspective. Instead of anchoring the viewer at a single position, the Moving Focus prints fracture and multiply the vantage points, requiring the eye to move across the composition in a constant state of adjustment. color becomes the glue that holds this perceptual experiment together.

In works such as Two Pembroke Studio Chairs Hockney deploys vivid fields of red, yellow, and blue not simply to fill space but to construct it. A wall rendered in blazing yellow does not recede quietly into background; instead, it asserts itself as an active participant in the composition. Chairs, tables, and architectural features are defined less by contour than by the intensity of their coloration. In this way, color is not subordinate to line but becomes a primary agent of spatial organisation.

The palette of the Moving Focus prints is strikingly exuberant. Hockney does not hesitate to place acid greens beside magentas, or deep ultramarines alongside fiery oranges. These juxtapositions are deliberately jarring, creating a rhythm of contrasts that keeps the eye in motion. The vibrancy echoes the very title of the series: focus is never static but constantly shifting, and color drives this visual dynamism.

Equally important is the emotional tenor of the palette. The Moving Focus works radiate joy and optimism, a celebration of the act of seeing itself. While Cubism often produced muted, analytical compositions, Hockney reinvigorates its fractured spaces with color’s exuberance, transforming intellectual experiment into visual delight. It is this combination of rigorous formal innovation and sensory pleasure that makes the Moving Focus series one of the most important achievements of late twentieth-century printmaking.

Digital color: The iPad Works

Hockney’s turn to digital technology in the late 2000s marked another significant chapter in his chromatic exploration. While many artists of his generation resisted digital tools, Hockney embraced them with characteristic curiosity. The iPad, with its intuitive interface and infinite palette, became a new medium for exploring color.

The most striking feature of the iPad works is their luminosity. Unlike traditional pigments, which reflect light, digital colors are illuminated from within by the screen itself. This gives Hockney’s digital works a unique glow, a sense of immediacy that recalls stained glass or backlit transparencies. He exploited this property to capture fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, particularly in his landscapes of Yorkshire.

In his series of iPad drawings depicting the changing seasons, Hockney’s palette becomes a record of temporal flux. Spring is rendered in radiant greens and soft pinks, autumn in fiery oranges and golds, winter in muted blues and greys. These colors are never neutral but always heightened, capturing not only the physical appearance of the landscape but also its emotional resonance. The works suggest an almost Fauvist intensity, where color conveys the very rhythm of life’s cycles.

Hockney’s iPad works also demonstrate the spontaneity afforded by digital media. The ability to draw directly with one’s finger or stylus, to select colors instantly, and to work without the delays of preparation, gave Hockney a new immediacy. This spontaneity is reflected in the freshness of the palette: skies streaked with electric pinks at dawn, hedgerows blazing with violets, and fields saturated with emeralds. These are not laboured reconstructions but quick, luminous impressions of the world as seen in a moment.

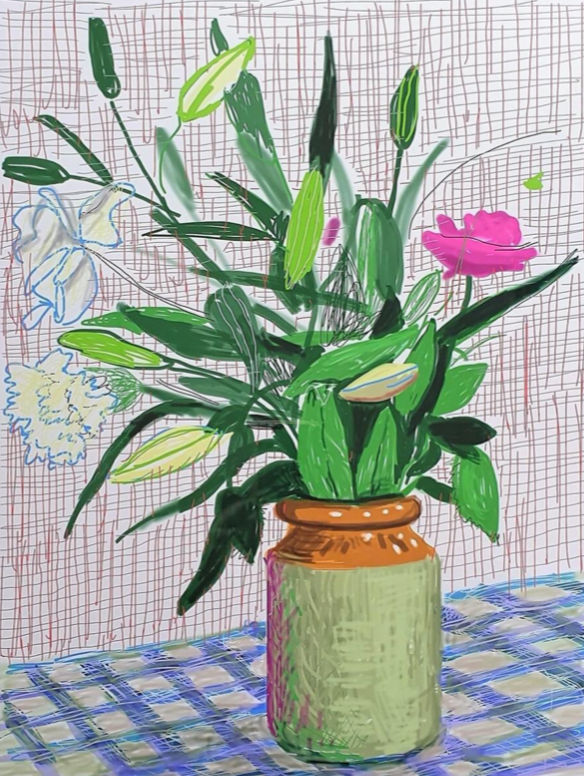

Crucially, Hockney’s embrace of the iPad did not represent a rejection of tradition but an extension of it. He often likened the iPad to printmaking, noting that both involve reproducibility. Yet his color ensured that no two works felt mechanical. Each digital drawing pulses with individuality, a reminder that technology need not strip art of human expressiveness when placed in the hands of a master colorist. iPad drawing 516 demonstrates this masterful use of color and shape.

David Hockney’s The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011—Selected Works

Within the larger Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 series, five works serve as powerful chromatic benchmarks in the unfolding seasonal narrative: 22 March, 26 April, 27 April, 17 May, and 30 May 2011. Below is an academic interpretation of each, placing them in context within Hockney’s chromatic and perceptual project:

The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011, 22 March 2011

This early spring drawing captures a landscape teetering between dormancy and bloom. The sky is overcast in pinkish-grey tones, while the grass below vibrates with an almost acidic green—an unsettling contrast that signals latent life beneath the surface. In this work, bare branches stand against a soft but charged backdrop, intimate in scale yet expansive in its emotional resonance. It reflects Hockney’s capacity to suggest the threshold of change, using color to mediate between the stillness of winter and emerging warmth of spring.

The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011, 26 April 2011

By late April, Hockney’s palette has shifted into richer territory. This piece retains the composition’s contemplative clarity but introduces deeper emeralds and warmer tones, signaling that the season is gaining momentum. The renewed vibrancy underscores nature’s unstoppable ascent. The tension between the memory of winter’s restraint and the exuberance of spring is palpable here, achieved through a subtle but expressive intensification of color.

The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011, 27 April 2011

Just one day later, Hockney pushes further into lush saturation. The sky is brighter, blossom begins to enliven branches, and figures of movement—whether wind or light—seem embedded in the leaves' hue. The immediacy of the iPad medium gives this work a shimmering spontaneity, while the chromatic escalation conveys the suddenness with which spring unfolds across the Yorkshire countryside.

The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011, 17 May 2011

Mid-May marks a clear transition into late spring. The palette here is rich with flaring reds, deep greens, and hints of gold—colors that evoke the fullness of the season. Blossoms may have widened into leaves, but Hockney continues to imbue the foliage with emotional resonance. This work exemplifies how, in his digital landscapes, color becomes a vessel not just for natural description but for translating the vitality of a lived moment.

The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011, 30 May 2011

By the end of May, spring has reached a gleaming fullness. The palette is lush and saturated, with dynamic interplay between aqua blues, blazing greens, and warm blossoms. The vibrancy of this work captures not merely the appearance of late spring but its emotional crescendo—the culmination of a sensory journey from quiet emergence to full bloom.

Contextual Integration

These five works chart the chromatic and perceptual evolution central to Hockney’s iPad landscape series. Beginning with 22 March 2011, where restrained tones hint at spring's coaxing, and advancing through 26 and 27 April, which reveal nature’s blossoming energy, the journey culminates in 17 and 30 May 2011, where color speaks most directly of renewal, exuberance, and visceral presence.

Hockney’s decision to title each work precisely, noting the date, reflects a diaristic approach—a commitment to temporality and the visual record of transformation. Through the iPad's immediacy, these works become not just landscapes, but temporal documents of change. His chromatic shifts are both observational and expressive, rendering the familiar Woldgate hedgerows as profoundly fresh encounters with nature’s cycle.

These pieces underscore Hockney’s underlying thesis: that color is not merely descriptive, but phenomenological. The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate works demonstrate how color can embody emotion, memory, and environmental rhythms, drawing the viewer into the experience—an immersion in time, in place, and in perception itself.

David Hockney, Matelot Kevin Druez 1, 2009

David Hockney’s Matelot Kevin Druez 1 (2009) belongs to a significant moment in his career when the artist was re-engaging with portraiture through the use of new digital technologies. Created on a computer using digital drawing software, this portrait marks Hockney’s early exploration of the possibilities of the screen as a medium. Long before the now-iconic iPad works of the 2010s, pieces such as Matelot Kevin Druez 1 demonstrate how Hockney was already embracing technology as a means to extend the painterly tradition into the twenty-first century.

The subject, Kevin Druez, is depicted in the formal attire of a French naval sailor—his uniform immediately anchoring the portrait in cultural and symbolic associations. The word “MATELLOT” (French for sailor) itself carries both literal and art-historical connotations. In the history of modern art, the sailor has been a recurring figure, associated with vitality, eroticism, and the everyday heroism of working men. Artists such as Jean Cocteau, Paul Cadmus, and even Picasso at moments drew on the visual archetype of the sailor. Hockney’s decision to portray Druez in naval uniform thus connects him to this longer lineage while also situating the subject within the contemporary moment.

Chromatically, the portrait is striking. The sailor’s dark blue uniform is enlivened by sharp accents of red on the cuffs and cap, and a crisp white collar, all of which are set against a rhythmic background of vertical green and turquoise strokes. The background, while abstract, is not neutral: its vibrating energy offsets the stillness of the sitter, infusing the composition with an almost theatrical vitality. The digital medium allows Hockney to layer marks quickly, achieving a surface texture that oscillates between drawing and painting. The luminous glow of the colors—particularly the subtle pinks of the sailor’s face and hands—further reflects the technological origin of the image, where light rather than pigment defines hue.

Psychologically, Matelot Kevin Druez 1 conveys both presence and distance. The sailor sits on a simple stool, his hands relaxed yet slightly awkward in their placement, one holding a cigarette with a casual familiarity. His expression is cool, reserved, almost detached, echoing the tradition of portraiture where sitters both reveal and conceal their identities. Hockney resists overworking the facial features, instead suggesting character through gesture, posture, and the chromatic environment in which the sitter is embedded.

This portrait is also notable for its continuity with Hockney’s lifelong interest in male beauty and homoerotic undertones. The sailor, historically a symbol of masculine allure, is here presented with dignity and directness, avoiding caricature while still tapping into the aestheticized traditions of sailor imagery in twentieth-century art.

Matelot Kevin Druez 1 ultimately demonstrates Hockney’s ability to merge tradition and innovation. By choosing a classically charged subject—the sailor—while rendering it in a radically new digital medium, Hockney both honours and reinvents portraiture. The vibrancy of the palette, the immediacy of line, and the glowing luminosity of the surface all signal how color and technology can reinvigorate one of art’s oldest genres. It foreshadows the explosion of digital portraiture in Hockney’s subsequent iPad drawings, situating this work as a key transitional piece in his oeuvre.

Across both the Moving Focus series and the iPad works, Hockney treats color not as a secondary property but as an experience in itself. His famous remark, “I prefer living in color,” encapsulates this philosophy. For Hockney, color is not a veneer placed upon form but a way of inhabiting the world more fully.

The chromatic intensity of his prints conveys this experiential dimension. When we encounter a Hockney print saturated with vibrant tones, we are not simply seeing an image but undergoing a heightened perception. color becomes a medium of empathy, drawing viewers into a shared delight in looking. This accounts for the enduring popularity of his work among collectors and audiences alike: Hockney’s colors are democratic, accessible, and immediately engaging, yet underpinned by a deep art-historical seriousness.

David Hockney’s legacy as a colorist cannot be overstated. His prints, the Moving Focus series, and the iPad works all demonstrate how color can be liberated from naturalism without losing its truthfulness. His palette is not a distortion of reality but an amplification of it, revealing the intensity of perception and the joy of looking.

In the broader history of art, Hockney’s chromatic innovations place him in dialogue with the great masters of color, from Matisse to the Abstract Expressionists. Yet his achievement is distinctive in its rootedness in everyday observation. Where Matisse often sought decorative harmony, and Rothko pursued transcendent emotion, Hockney grounds his color in the concrete act of seeing: a swimming pool under California light, a Yorkshire hedgerow in spring, or the kaleidoscopic interior of a room.

Through his fearless embrace of vibrant tones, Hockney has secured his position as one of the greatest colorists of the modern era. More than a stylistic device, his color embodies a philosophy of life—optimistic, experimental, and always alert to the beauty of the visible world.

Discover signed David Hockney prints for sale and contact our galleries via info@guyhepner.com