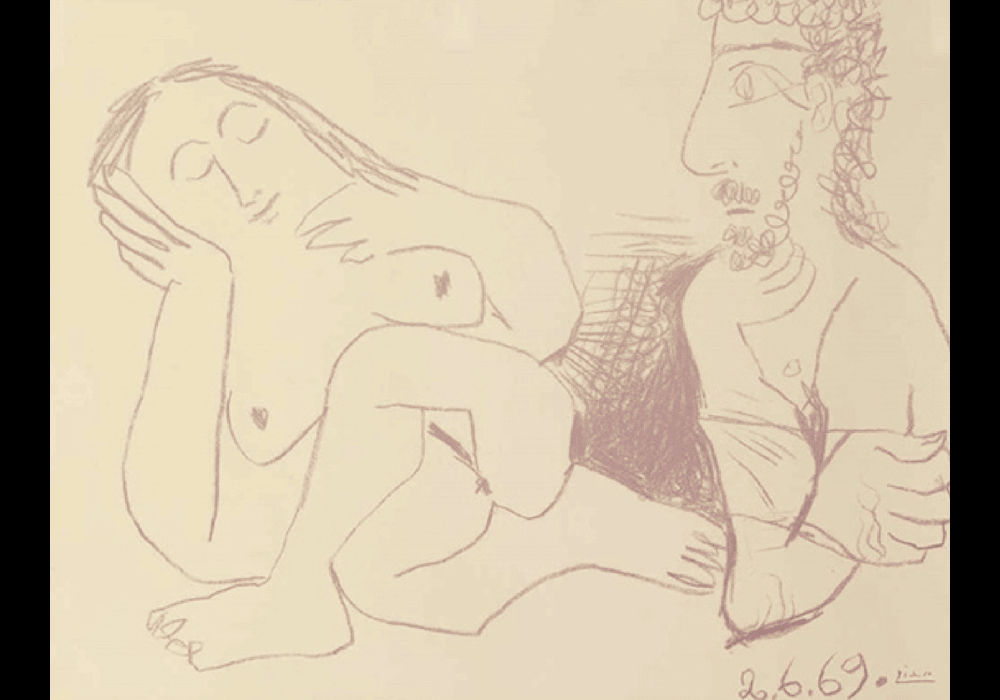

“When I was a child my mother said to me, 'If you become a soldier, you'll be a general. If you become a monk, you'll be the pope.' Instead I became a painter and wound up as Picasso.”

-

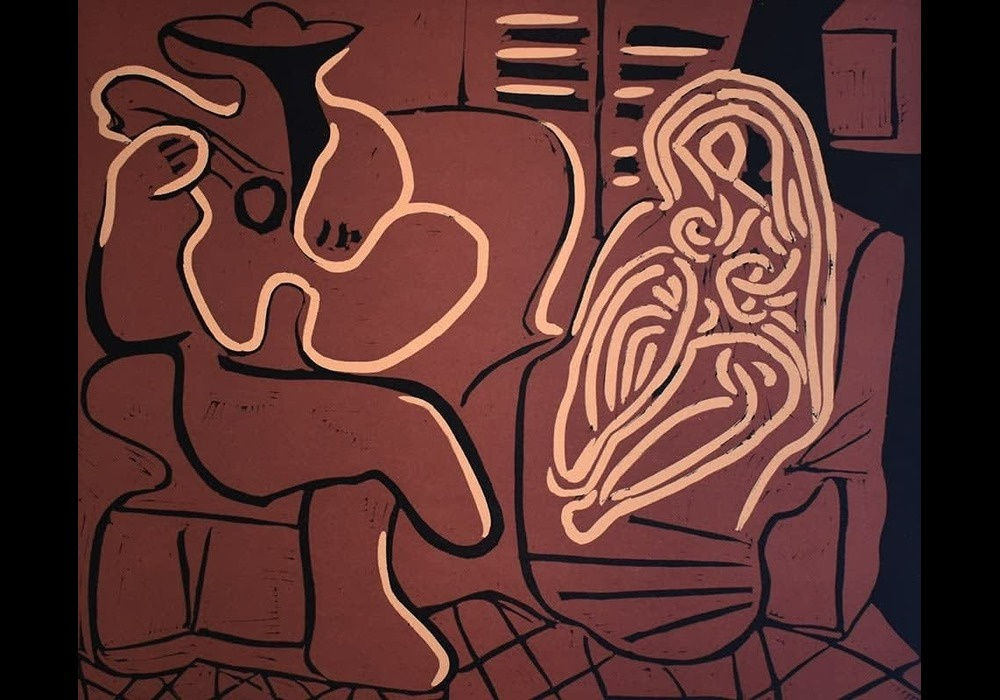

Futurism drew on his fractured Cubist forms to express speed and motion.

-

Dada and Surrealism adopted his use of found objects and unconscious symbolism.

-

Abstract Expressionists saw in his late works a model for gestural freedom and emotional depth.

-

Pop artists followed his lead in collapsing high and low culture, realism and abstraction.

-

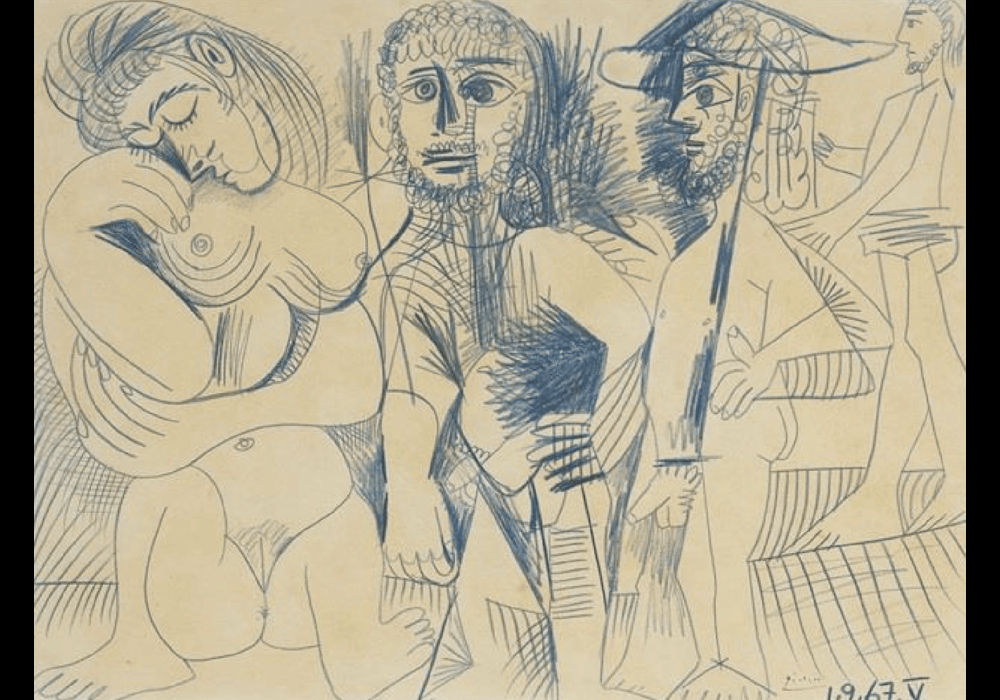

Contemporary artists continue to grapple with his legacy—sometimes emulating, sometimes rebelling, but never ignoring.