Keith Haring is best known for his explosive street-inspired visual language—radiant babies, barking dogs, and writhing figures outlined in bold, cartoon-like strokes. Yet beneath the vibrant colors and kinetic energy lies a deep and evolving exploration of line, gesture, and form. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his powerful works in sumi ink on paper.

This lesser-known but profoundly expressive body of work highlights a subtler side of Haring’s practice—one that marries his spontaneous visual instincts with the discipline and elegance of East Asian brush painting. By adopting sumi ink, a traditional Japanese medium, Haring aligned himself with centuries-old artistic traditions while continuing to communicate his radical, contemporary message. The results are works that are at once urgent and timeless, minimalist and monumental.

What Is Sumi Ink?

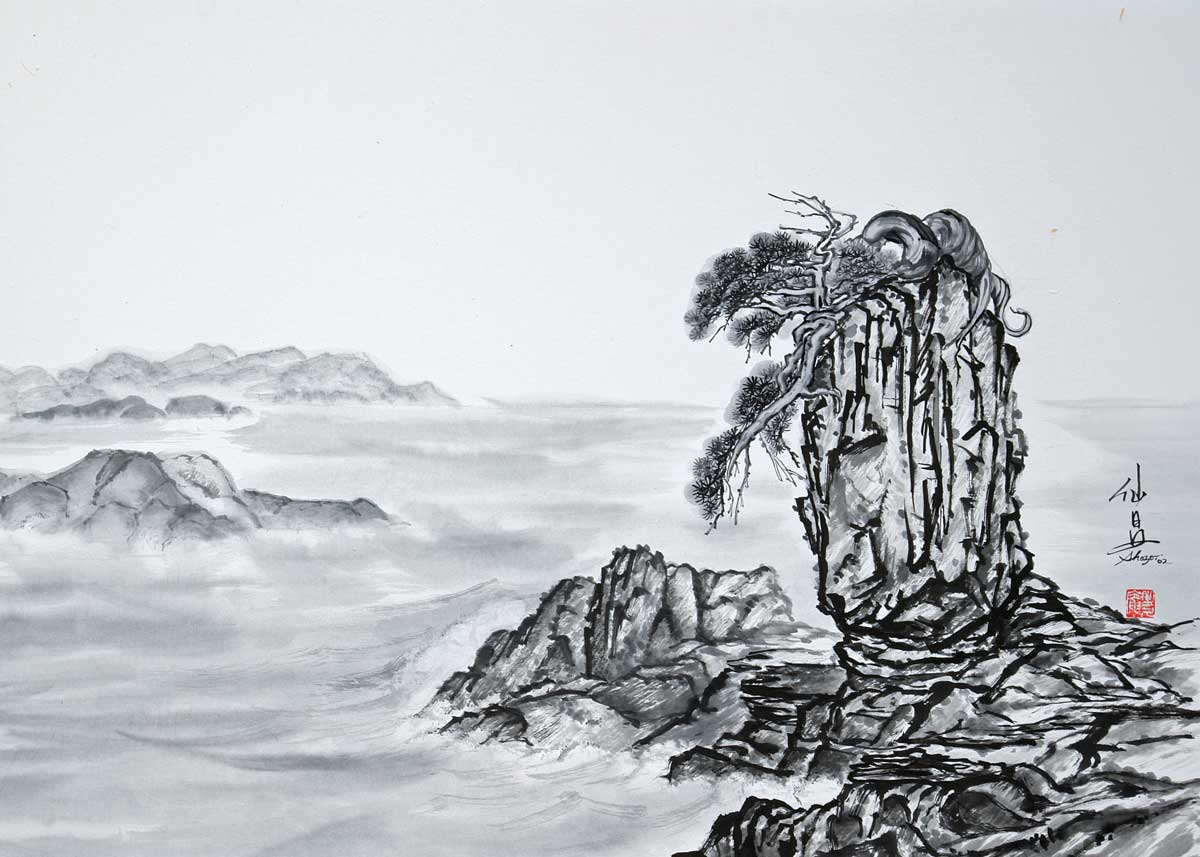

Sumi ink is a black ink traditionally used in East Asian calligraphy and brush painting, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea. It is made from soot—often from pine or oil—mixed with animal glue, then formed into ink sticks and ground with water on an inkstone. Known for its depth, range of tonalities, and fluid application, sumi ink has been a central material in Zen art, poetry, and philosophy for centuries.

Unlike Western inks that often emphasize permanence and uniformity, sumi ink is prized for its impermanence, expressive variation, and spiritual depth. Each stroke becomes a record of the artist’s energy, breath, and focus in the moment—a perfect match for Haring’s instinctive and performative style.

A Perfect Medium for Gesture and Urgency

Haring’s use of sumi ink amplified what was already central to his work: the power of line.

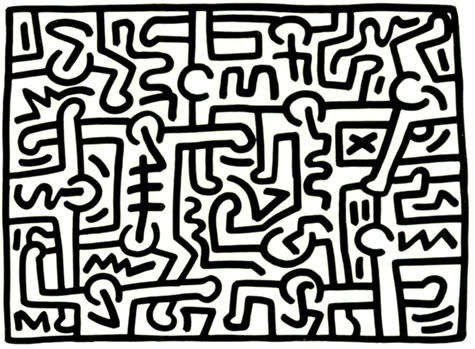

Sumi ink on paper allowed Haring to emphasize gesture and immediacy. Without the aid of underdrawings or revisions, he would apply sweeping lines directly to paper using a brush, often in a single, continuous movement. This required not only precision and confidence, but an almost meditative clarity—qualities that deeply resonated with the principles of Japanese ink painting.

The medium’s characteristics—its flowing quality, its capacity for absorbing into the paper and blurring at the edges—allowed Haring to explore new modes of mark-making. Lines could swell and fade in a single stroke, creating dynamic shifts in weight and tone. The energy of Haring’s figures, so often electric and celebratory in his acrylic works, here became more introspective and raw.

The resulting drawings are visceral, fluid, and deceptively simple, yet they retain the symbolic potency that defined all of Haring’s visual language. The brush strokes move like dance or music—natural extensions of Haring’s body—imbuing the paper with rhythm, life, and emotion.

Keith Haring Untitled 1984, 1984

Japanese Aesthetics and Haring’s Artistic Philosophy

Haring’s affinity for sumi ink was not a casual choice—it was part of a broader appreciation for Japanese art and culture that shaped his thinking.

In the mid-1980s, Haring traveled to Tokyo, where he held solo exhibitions and collaborated with Japanese brands. He was deeply influenced by the minimalist aesthetics, spiritual grounding, and graphic clarity found in Japanese calligraphy, Zen painting, and ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige, along with calligraphic masters, served as visual and philosophical inspirations.

This influence dovetailed with Haring’s own commitment to creating work that was both accessible and symbolic. Like the Japanese calligraphers who valued direct, unmediated mark-making, Haring embraced improvisation and flow. He once said:

“I don’t think about what I’m doing when I’m drawing... I just let it happen.”

This surrender to the moment is central to Zen aesthetics, where the brush becomes an extension of the mind, and each line reflects the artist’s internal state. In sumi ink, Haring found a vehicle for these same ideals—a union of mind, body, and medium.

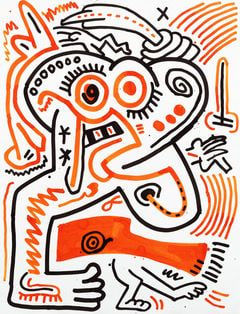

Keith Haring Untitled March 9, 1988

From Subway Walls to Sacred Scrolls

Haring’s sumi ink works on paper diverge significantly from the public murals and colorful prints that made him famous. They are often larger in scale, sometimes occupying long vertical scroll formats reminiscent of traditional hanging scrolls in East Asian art.

These sumi works are typically devoid of color. Without the vibrant palette of his Pop Art sensibility, the focus shifts to pure form, balance, and space. The use of negative space—the untouched paper—is as important as the brushwork itself, a concept central to Japanese painting. It allows the viewer to breathe, to pause, to reflect.

Yet even in this monochrome realm, Haring’s figures remain unmistakable. Human forms contort in motion, animals lunge or leap, serpents twist into cosmic spirals. These are not meditative in a tranquil sense—they are meditations on life, chaos, sensuality, and mortality, rendered in a single breath of ink.

Spirituality and the Body

Haring’s sumi ink works often engage with the spiritual and the corporeal in tandem. The black brushwork, fluid and uninterrupted, mirrors the human body in motion—its limbs, breath, and heartbeat. These works strip away narrative and detail to reach a more primal, archetypal mode of expression.

They also reflect the existential urgency that permeated Haring’s late work, as he grappled with his diagnosis of HIV. In sumi ink, he found a medium that could express not just his aesthetic ideas, but his emotional and spiritual journey. The immediacy of brush on paper mirrored the immediacy of his life—fleeting, unedited, alive.

Exhibitions and Legacy

Though fewer in number than his acrylics or silkscreens, Haring’s sumi ink drawings have been featured in numerous exhibitions that highlight the contemplative side of his practice. Museums such as the Brooklyn Museum, the Tate, and the Nakamura Keith Haring Collection in Japan have exhibited these works to great acclaim.

Collectors and scholars increasingly view Haring’s sumi ink works as key to understanding the full depth of his artistry. They are not side projects or aesthetic experiments—they are integral expressions of Haring’s vision, drawing together his love of line, his reverence for Eastern philosophies, and his desire to speak directly to the viewer through unfiltered expression.

Keith Haring Drawing For The Monte Carlo Ballet , 1989

Line as Lifeline

Keith Haring’s use of sumi ink on paper is a testament to his versatility, curiosity, and depth as an artist. In these works, we see Haring not just as a pop icon or street artist, but as a philosopher of the line, a calligrapher of the body, a bridge between East and West.

In sumi ink, he found a medium that matched his speed, his spontaneity, and his soul. It stripped away distraction and let the essence of his art shine through. Whether one sees these works as drawings, gestures, or meditations, one thing is clear: they remain among the most direct, intimate, and powerful expressions of Keith Haring’s lifelong belief that art is a force for connection, freedom, and truth.

Discover Keith Haring prints for sale and contact our New York and London galleries via info@guyhepner.com for latest availabilities.