Roy Lichtenstein’s five-decade career reflects a far more nuanced and evolving exploration of American culture, visual language, and art history. From early expressionist experiments to his late formalist deconstructions of brushstrokes and art historical references, Lichtenstein’s body of work reveals an artist continuously reexamining the boundaries of style, originality, and visual perception.

Early Work: Expressionist Beginnings and Americana

Lichtenstein’s early career in the 1940s and ’50s was marked by a search for personal expression within prevailing modernist traditions. After studying under artists like Reginald Marsh and immersing himself in the American Scene movement, he began producing semi-figurative work heavily influenced by Cubism, German Expressionism, and Abstract Expressionism. These paintings often included American icons such as cowboys, George Washington, and folkloric characters rendered in a painterly, gestural manner.

Even at this stage, Lichtenstein was interested in popular culture and Americana. However, his treatment of these subjects was more earnest than ironic. He was not yet parodying or stylizing the content—rather, he was searching for a distinctive visual voice amid the prevailing winds of Abstract Expressionism, which still dominated the postwar art world.

The Pop Breakthrough: Comic Books and the Ben-Day Dot (1961–1965)

Lichtenstein’s breakthrough came in 1961 when he created a series of paintings based directly on comic books and consumer advertising. Works like Look Mickey (1961), Whaam! (1963), and Drowning Girl (1963) featured melodramatic scenes lifted from romance and war comics, recreated with bold black outlines, primary colors, and the signature Ben-Day dots used in mass printing.

These works marked a radical departure from the gestural spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism. Instead of celebrating the artist’s hand, Lichtenstein mimicked mechanical reproduction. His brushwork was so precise and impersonal that it appeared printed, not painted. This stylistic innovation wasn’t merely aesthetic—it was a critique of the sanctity of originality and authorship in high art.

Lichtenstein’s early Pop works were controversial. Critics accused him of plagiarism, while others celebrated his ability to elevate lowbrow imagery into high art. But beneath the surface, these works were more than mere copies. Lichtenstein often altered the composition, cropped images, changed colors, and added new text to create heightened emotional drama and formal balance. His work reflected a sophisticated understanding of artifice, narrative, and the visual economy of mass media.

Commercial Culture and Interior Spaces (Mid–Late 1960s)

As the 1960s progressed, Lichtenstein expanded his subject matter beyond comic strips. He explored advertisements, product packaging, and design motifs, often focusing on the aesthetic vocabulary of mid-century American life. Paintings such as Bathroom (1961) or The Refrigerator (1962) revealed the everyday as stylized and idealized spaces, dissecting the manufactured dreams sold to the American public.

![]()

Lichtenstein also began producing sculptural works and painted ceramics, maintaining the flat, graphic quality of his paintings. These explorations signaled his growing interest in surface, objecthood, and the fluid boundaries between two-dimensional and three-dimensional representation.

Art About Art: The Parodic and the Canonical (Late 1960s–1970s)

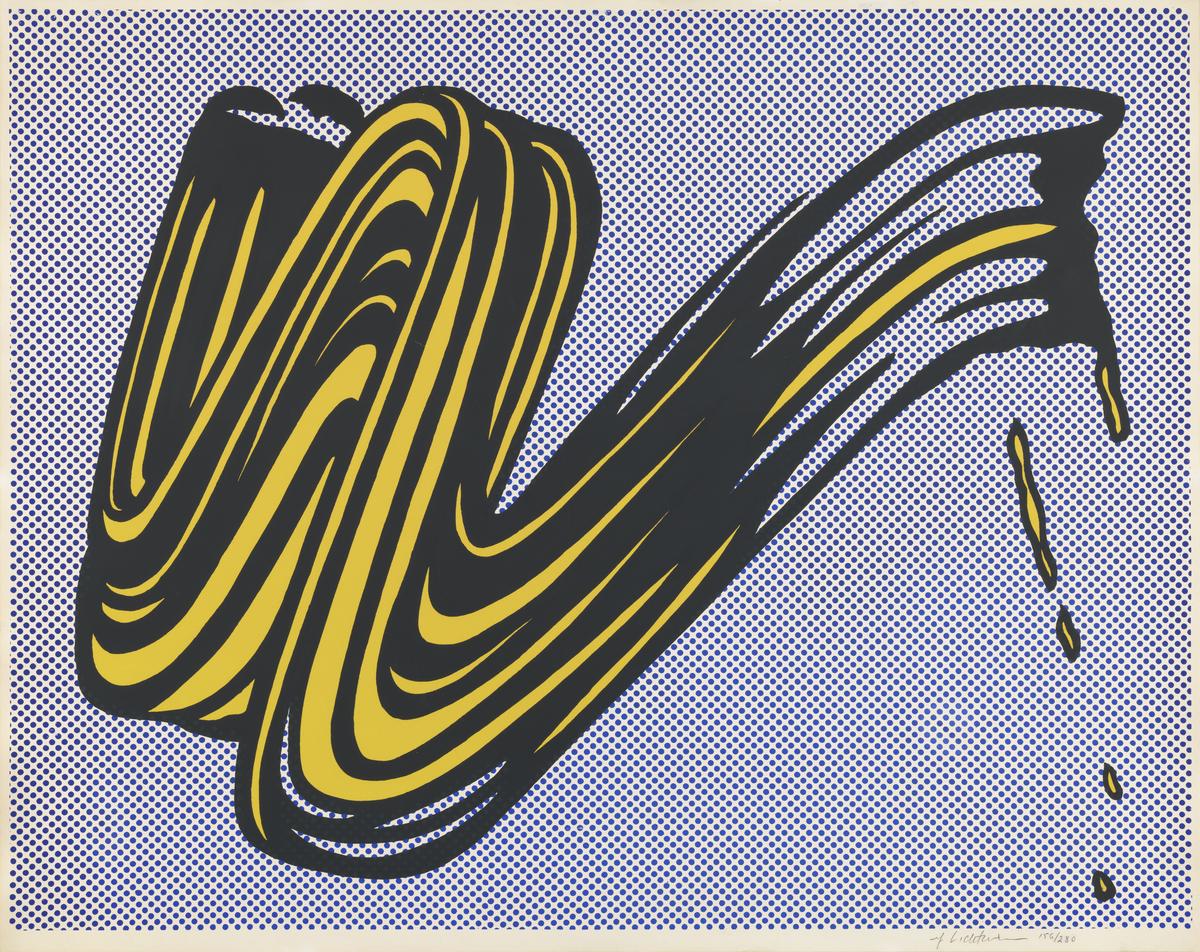

By the late 1960s, Lichtenstein’s work shifted toward a more conceptual exploration of art history. He began producing “quotation” paintings—images that mimicked the styles of other artists or artistic movements. His Brushstroke series parodied Abstract Expressionism’s gestural marks by rendering them as static, graphic icons. These brushstrokes were mechanized—clean, uniform, and devoid of spontaneity.

Simultaneously, he turned his attention to the great artists of Western painting—Picasso, Monet, Matisse, and Mondrian among them. Lichtenstein recreated their works in his own visual language, complete with Ben-Day dots and comic-book flatness. His Haystacks and Rouen Cathedral series (1969) reimagined Monet’s Impressionist studies as pixelated, synthetic landscapes, devoid of atmospheric nuance. This was both homage and critique, a way of re-situating canonical art within the postmodern conversation about simulacra and style.

The Studio and Mirrors: Self-Reflexive Experiments (1970s–1980s)

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Lichtenstein became increasingly self-referential. His Artist’s Studio series depicted studio interiors filled with his own paintings—a painting of a painting of a painting. These recursive compositions engaged with questions of authorship, identity, and the visual environment of the artist.

Lichtenstein’s Mirror paintings are among his most conceptually rich works. At first glance, they appear blank—simple, grey ovals and rectangles. Yet they are visual paradoxes: images of something that cannot be depicted (a reflection), rendered in a style that implies flatness and surface. The Mirror series explored perception, illusion, and abstraction, subtly pointing to the limits of pictorial representation.

Late Work: Chinese Landscapes, Nudes, and the Return to Abstraction (1990s)

In the final decade of his career, Lichtenstein continued to push stylistic boundaries. His Chinese Landscape series referenced traditional East Asian ink painting, but through a Pop lens—stylized clouds, geometric waves, and synthetic brushstrokes replaced calligraphic gestures. These paintings emphasized the universality of visual language while playing with cultural translation and appropriation.

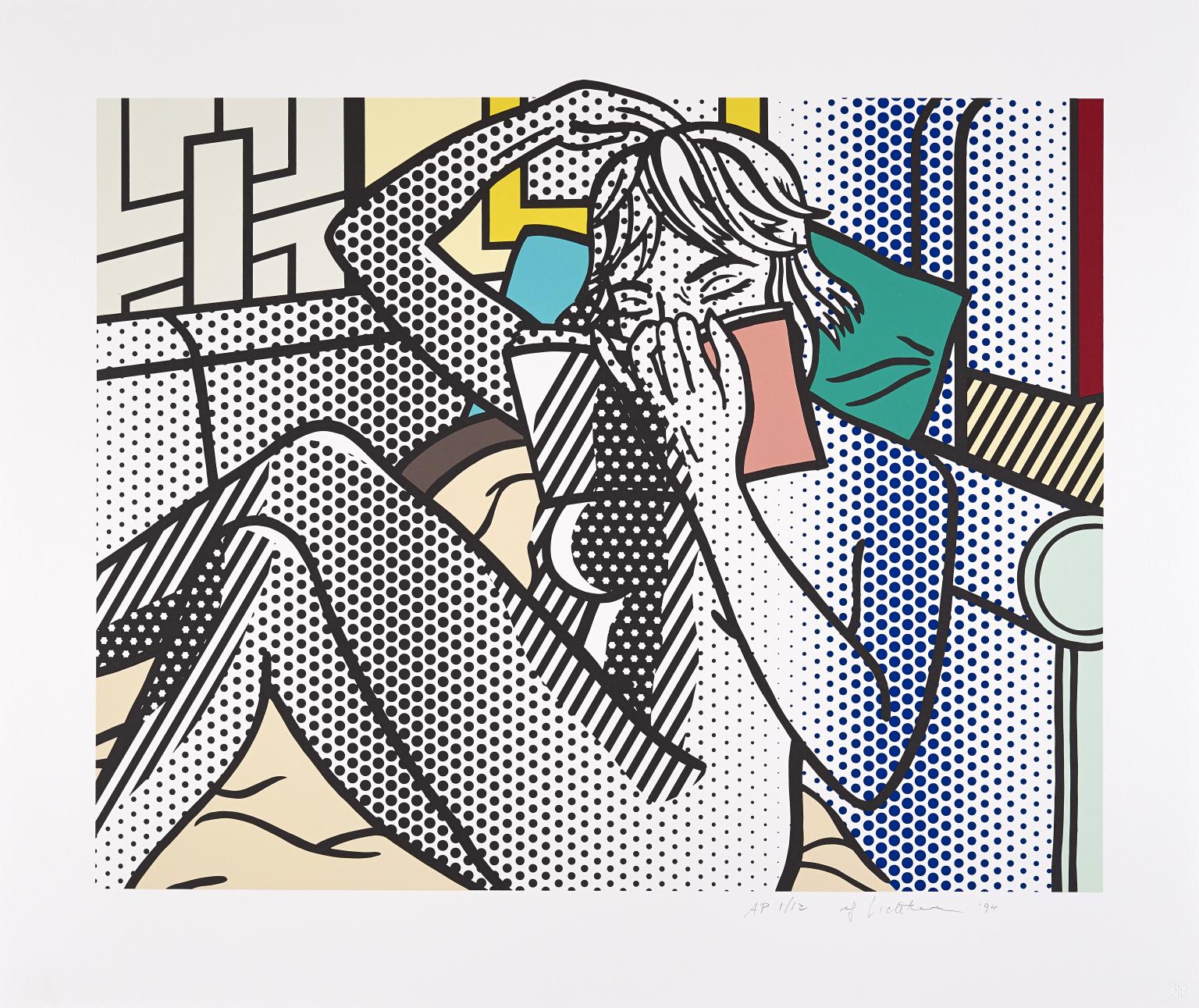

His late Nudes series, begun in the mid-1990s, returned to the comic-book aesthetic but with a twist. These voluptuous female forms were rendered in a style more abstract and formalist than his early Pop heroines. The emphasis was on composition, color, and line rather than narrative drama. The Nudes reflect a mature synthesis of Lichtenstein’s interests—combining figuration, stylization, and formal experimentation into a single body of work.

Lichtenstein also returned to abstract motifs, especially in his Perfect/Imperfect series. These geometric compositions extended the idea of mechanical drawing and played with the tension between mathematical order and painterly execution.

Though the Ben-Day dot remains Lichtenstein’s most famous visual trademark, his career was anything but one-dimensional. He constantly shifted themes, styles, and references to interrogate the nature of art itself. His evolution from comic-book parody to philosophical explorations of perception and image-making reflects a deep engagement with modernism, postmodernism, and the visual culture of the 20th century.

Today, Lichtenstein is celebrated not just as a Pop artist but as a conceptual pioneer who helped redefine what painting could be. He transformed everyday imagery into a platform for critical reflection, creating work that continues to challenge and seduce with its boldness, humor, and intellectual rigor. Discover signed Roy Lichtenstein prints for sale and contact our gallery for latest works via info@guyhepner.com. Looking to sell? We can help. Contact our New York and London galleries and discover how our experienced team can help to sell your Roy Lichtenstein prints.