In the landscape of modern and contemporary art, few figures have transcended the traditional confines of the gallery and entered the broader cultural consciousness like Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Roy Lichtenstein. More than just celebrated artists, they are now global brands—shorthand for entire movements, aesthetics, and ideologies. But what transformed these men from creators to cultural icons? The answer lies in how each of them instinctively understood—and shaped—the evolving intersection between art, celebrity, commerce, and identity.

Andy Warhol: The Godfather of Self-Branding

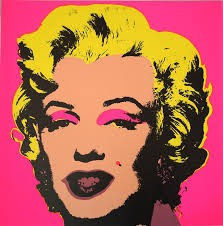

Warhol didn’t just depict celebrity—he manufactured it. By the 1960s, he had turned his studio, The Factory, into a production line for art, personas, and mythologies. He wore silver wigs, surrounded himself with rising stars, and understood the visual economy of fame before the Instagram age. His works—Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyn Monroe portraits, and dollar signs—weren’t just art, but logos of a new cultural currency.

Warhol’s personal detachment and mechanical repetition became the brand strategy of an era obsessed with consumption. He once famously said, “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art,” blurring the line between artist and entrepreneur. Today, his image, like his art, is instantly recognizable and endlessly reproduced. Discover Andy Warhol signed prints for sale.

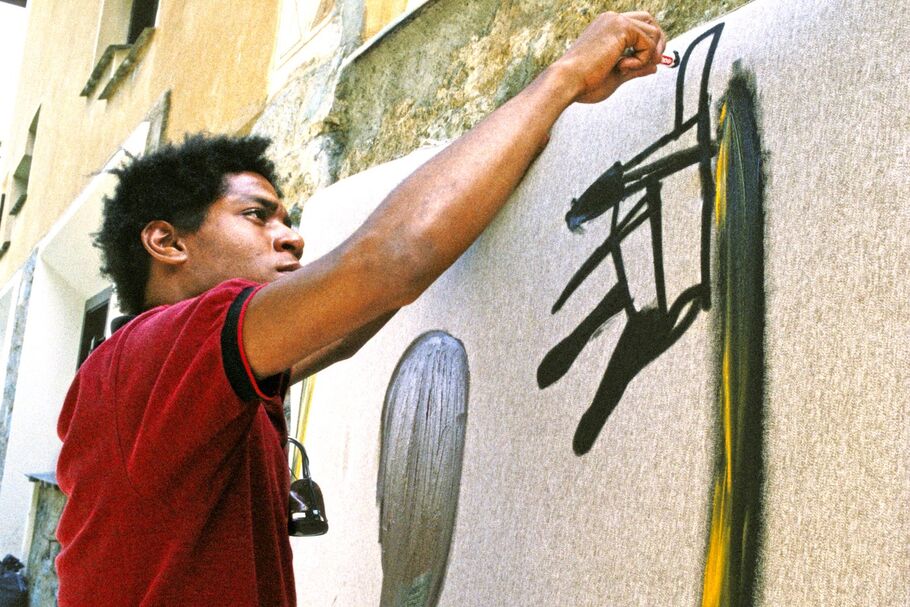

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Identity as Icon

Basquiat’s branding was rooted in raw authenticity and cultural defiance. Starting as the elusive street tagger “SAMO,” he crafted a visual language that merged Afro-Caribbean heritage, hip-hop, anatomy, history, and poetry. His meteoric rise from graffiti artist to international sensation made him a symbol of rebellious genius—an anti-establishment figure who infiltrated the art world on his own terms.

Basquiat’s signature crown motif, skeletal figures, and frenetic mark-making evolved into visual trademarks. Unlike Warhol’s polished surfaces, Basquiat’s chaos became a brand of its own—one that resonates with themes of race, power, and struggle. Even decades after his death, he remains a powerful emblem for cultural resistance and artistic independence. Explore Jean-Michel Basquiat original art for sale.

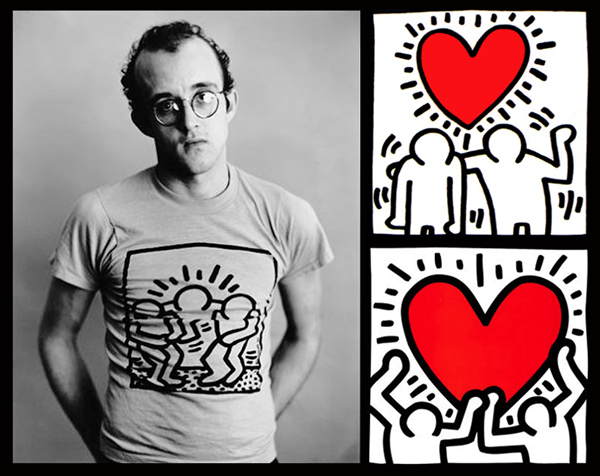

Keith Haring: Art for All

If Warhol embodied celebrity and Basquiat symbolized rebellion, Keith Haring stood for accessibility and activism. His figures—radiant babies, barking dogs, and dancing silhouettes—functioned like icons in a universal visual language. Haring’s art was meant to be seen and shared, from subway walls to t-shirts, from gallery spaces to hospitals.

He extended his brand through the Pop Shop, where he sold affordable art products emblazoned with his motifs. This wasn’t commercial dilution—it was mission-driven branding. Haring believed art should be part of everyday life. His graphic style, rooted in street culture and public art, made his work instantly recognizable—and his message of love, unity, and social justice unforgettable. Explore Keith Haring original art for sale.

Roy Lichtenstein: The Comic-Strip Strategist

Lichtenstein’s rise to fame came from his ability to abstract and reframe popular imagery. With a cool, ironic detachment, he appropriated comic book panels and transformed them into monumental canvases, complete with Ben-Day dots and melodramatic captions. “Whaam!”, “Oh, Jeff…”, and “M-Maybe” became not only works of art but catchphrases of the Pop era.

His consistent style and focus on mass media tropes made his work feel like advertising with a twist—familiar yet intellectual. Lichtenstein turned the idea of authorship on its head, challenging the high-low divide in art. The controlled consistency of his visual language, like a designer’s toolkit, became central to his brand and lasting appeal. Discover Roy Lichtenstein prints for sale.

The Rise of the Artist as Brand

What ultimately unites Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Roy Lichtenstein is not only their aesthetic innovation but their remarkable ability to understand and control the mechanics of image-making, personal narrative, and public visibility. These artists didn’t merely produce compelling works of art—they each crafted a persona, a language, and a mythos around themselves that could be recognized instantly, imitated endlessly, and commodified globally.

They understood—long before the internet or influencer culture—that being an artist in the modern world required more than creativity. It required building a brand.

Andy Warhol: The Brand of Celebrity

Andy Warhol turned celebrity itself into a medium. By creating portraits of stars like Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and Mick Jagger, he equated their faces with the same cultural weight as consumer products. But Warhol didn’t stop at depicting fame—he embodied it. With his silver wigs, monotone speech, and camera-ready mystique, he became as much a cultural icon as his subjects. Through The Factory, his art studio turned brand lab, he carefully controlled the production of his work and his persona, transforming himself into a living logo of Pop Art. In doing so, Warhol pioneered the modern concept of the artist as a fully formed, monetizable identity.

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Branding Cultural Resistance

Basquiat, by contrast, built his brand not around celebrity but around authentic defiance. His early graffiti under the pseudonym “SAMO” established a voice that was cryptic, poetic, and subversive. As he transitioned into the gallery world, Basquiat’s public image as a rebellious outsider—young, streetwise, and intellectually incisive—became inseparable from his art. His crowns, skulls, scrawled phrases, and anatomical references became recurring visual signatures that asserted Black identity and historical memory in a predominantly white art world. Even posthumously, Basquiat’s name has become a symbol of cultural critique and resistance—his brand rooted not in polish, but in unfiltered truth and urgency.

Keith Haring: The Brand of Visual Activism

Keith Haring embraced the idea that art could be both visually joyful and socially powerful. From the beginning, his figures and symbols were designed for legibility—accessible to all, regardless of education or art-world status. His use of recurring icons like the Radiant Baby, the barking dog, and the dancing figure formed a graphic language that was both deeply personal and widely universal. Haring’s activism—particularly around AIDS awareness, LGBTQ+ rights, and anti-apartheid movements—became inextricable from his imagery. Through the Pop Shop, Haring extended his brand into products, t-shirts, posters, and stickers, making his art available to the public without intermediaries. His brand became a model for merging advocacy, commerce, and mass cultural presence.

Roy Lichtenstein: The Brand of Irony and Critique

Roy Lichtenstein approached branding with cool detachment. His art was rooted in irony, replication, and critique, and so was his persona. By appropriating comic book panels and reproducing them in the high-art context, he turned mass communication into fine art, and his identity as an artist became one of a cultural observer—dispassionate, clever, and calculated. His consistent use of Ben-Day dots, speech bubbles, and dramatic exclamations gave his work the feel of a visual brand system, much like a modern design identity. Lichtenstein didn’t just critique media—he became media. His brand was built on the clarity of his irony and the familiarity of his language.

Today, the influence of these artists stretches far beyond galleries and museums. Their work appears on skateboards, sneakers, handbags, and hotel walls. Their estates manage robust licensing programs, partnering with fashion houses, consumer brands, and cultural institutions. Their images are integrated into advertising, digital emojis, and mass-market design, proving that the boundary between fine art and lifestyle branding no longer exists—if it ever did.

In a world dominated by social media and visual storytelling, the model they established continues to resonate. The blueprint is clear:

"Be bold. Be distinct. Be everywhere."

These artists were not just creators. They were—and remain—cultural architects, whose identities became just as influential as their art.

Warhol, Basquiat, Haring, and Lichtenstein didn’t just change what we see in art—they changed how we see the artist. They prefigured today’s intersection of image, identity, and influence, showing that artistic legacy is as much about presence as practice.

In the end, their true masterpiece may not be any single artwork—but the brand of themselves.