The Cold War in Pop Art: Andy Warhol's Dialogue Between Communism and Capitalism

The Cold War, a global ideological standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union, was fought not on traditional battlefields but through politics, propaganda, and culture. While artists across the world responded to this moment with direct activism or opposition, few approached the subject with the nuance, irony, and visual power of Andy Warhol. Through his Pop Art lens, Warhol both reflected and reimagined Cold War symbols, capturing the essence of the global divide between communism and capitalism.

Warhol’s Political Pop: Art as Cultural Commentary

Known for his depictions of soup cans and celebrities, Warhol’s later work reveals a deeper engagement with politics—particularly during the Cold War era. While never overtly political in his public statements, Warhol used his art to explore how icons, whether cultural or political, are commodified and consumed. His work transcends ideology, focusing instead on the power of repetition, media, and image-making. Through a series of prints from the 1970s and 1980s, Warhol presents a visual dialogue between East and West, communism and capitalism, satire and seriousness.

Communism in Red: Hammer and Sickle, Mao, and Lenin

Hammer and Sickle (1977)

Warhol's Hammer and Sickle series emerged from a 1976 trip to Italy, where he noticed the communist emblem spray-painted across walls as graffiti. Instead of accepting the symbol as a straightforward political statement, Warhol isolated it, deconstructed it, and repurposed it. Using photographs of real tools, he created screenprints that rendered the hammer and sickle in dramatic compositions—some overt, others abstract. The series doesn’t glorify or condemn communism; instead, it frames the symbol as another image within the landscape of mass media, raising questions about its role in both propaganda and pop culture.

Mao (1972–1973)

Warhol’s Mao series was one of his first forays into political portraiture. Created shortly after President Nixon’s historic visit to China, the series portrays Mao Zedong, then Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, using the visual language of celebrity. Warhol transforms Mao into an object of aesthetic consumption, applying bright colors and cosmetic-like flourishes. These prints blur the line between dictator and icon, suggesting that political power, like fame, is rooted in image and repetition.

Lenin (1987)

Created near the end of Warhol’s life, the Lenin series presents the Soviet leader in a stark, intense pose. Unlike the playfulness of Mao, Lenin is more somber and austere, stripped of color aside from his signature red tie. The sharp contrast and minimalism suggest reverence, but the same screenprinting technique undercuts that seriousness. Warhol invites viewers to consider the function of Lenin’s image: is it to inspire, control, or simply to endure?

Capitalism in Color: Uncle Sam, Vote McGovern, and Jimmy Carter

Uncle Sam (1981)

A symbol of American patriotism, Uncle Sam is reimagined by Warhol in his Myths portfolio. While traditionally seen as a rallying figure, Warhol’s portrayal feels theatrical and hollow—more costume than conviction. This piece reflects how American ideals, too, can be repackaged and sold, suggesting that capitalism, like communism, is a performance dependent on image.

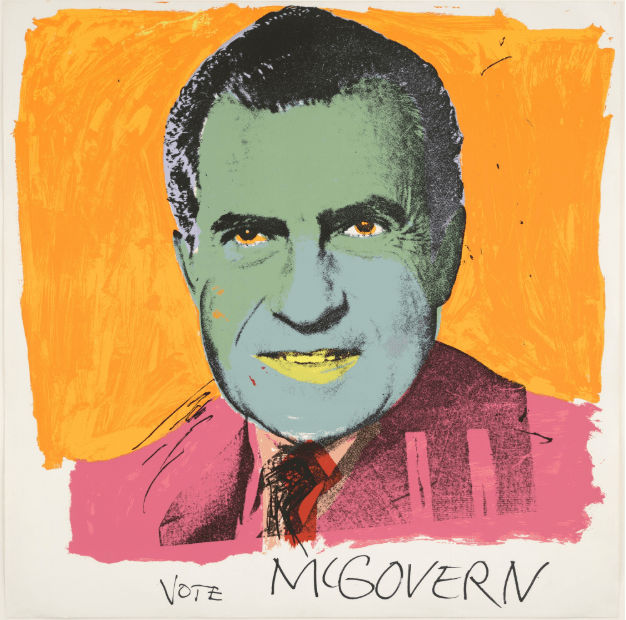

Vote McGovern (1972)

This politically charged print was one of Warhol’s most explicit critiques. Here, Warhol manipulates Richard Nixon’s portrait, tinting his face green and his suit pink to portray him as ghoulish and grotesque. Created in support of Democratic candidate George McGovern, the work demonstrates how Warhol could weaponize his aesthetic to serve a cause. Though atypical of his usually neutral stance, this image underscores the intense polarization of Cold War-era American politics. Explore more Vote McGoven.

Jimmy Carter (1976)

In contrast to the distorted Vote McGovern, Warhol’s portrait of President Jimmy Carter is calm, clean, and composed. Created during Carter’s campaign, the print reflects a different tone—more celebratory than critical. Here, Warhol treats Carter not as a caricature, but as a legitimate symbol of American democratic ideals. It’s a nod to hope and sincerity in a time overshadowed by Cold War anxieties.

East vs. West Through Warhol’s Eyes

Warhol’s Cold War works don’t present a binary of good versus evil. Instead, they explore how both ideologies rely on image-making to maintain power. Whether it’s Lenin’s stoicism, Mao’s celebrity-like aura, Nixon’s grotesquery, or Uncle Sam’s performative patriotism, Warhol uses the same Pop Art tools—bold color, repetition, and flatness—to reveal how propaganda operates on both sides.

Rather than taking sides, Warhol holds up a mirror to the 20th century’s most powerful figures and symbols. Through his art, he invites us not to choose between red or blue, East or West, but to consider how all systems of power depend on image, spectacle, and consumption.

Andy Warhol’s legacy as a political artist is often overlooked, but his work offers a sophisticated commentary on the Cold War’s battle of symbols. By placing communist and capitalist imagery in the same artistic framework, Warhol reminds us that the true Cold War battleground wasn’t just geopolitical—it was cultural, visual, and psychological.

In the age of media saturation and global iconography, Warhol’s Cold War-era works remain remarkably prescient. They challenge us to look beyond politics and into the mechanisms of power that shape our perceptions—and to recognize that, often, ideology is just a matter of design.

Explore Andy Warhol art for sale and contact info@guyhepner.com for latest availabilities. Looking to sell? We can help! Find out how to sell Andy Warhol prints with our New York and London galleries. Explore more Warhol content in What techniques did Andy Warhol use? The Five Most Famous Warhols and our Guide to Collecting Warhol.