Dismaland: Banksy's Bleak Wonderland and the Power of Situational Street Art

In the summer of 2015, the seaside town of Weston-super-Mare in the UK became the unlikely epicenter of a global art phenomenon. Beneath the facade of a derelict seaside lido, Banksy unveiled Dismaland, a temporary pop-up “bemusement park” that offered a searing, satirical twist on consumer culture, politics, and the art world itself. More than just a parody of Disneyland, Dismaland was a carefully crafted dystopia—a full-scale art installation with dark humor, powerful social commentary, and an unmistakable Banksy touch.

Dismaland wasn't just an exhibition; it was an immersive experience, a form of situational street art on steroids. It fit squarely within Banksy's ethos: art not just placed in a public space, but reactive to it—commenting on society in real-time, layered with irony, and designed to disrupt the viewer’s sense of normality. In this article we explore what Dismaland was and how it fits into Banksy’s wider modus operandi.

A Park of Unease: What Was Dismaland?

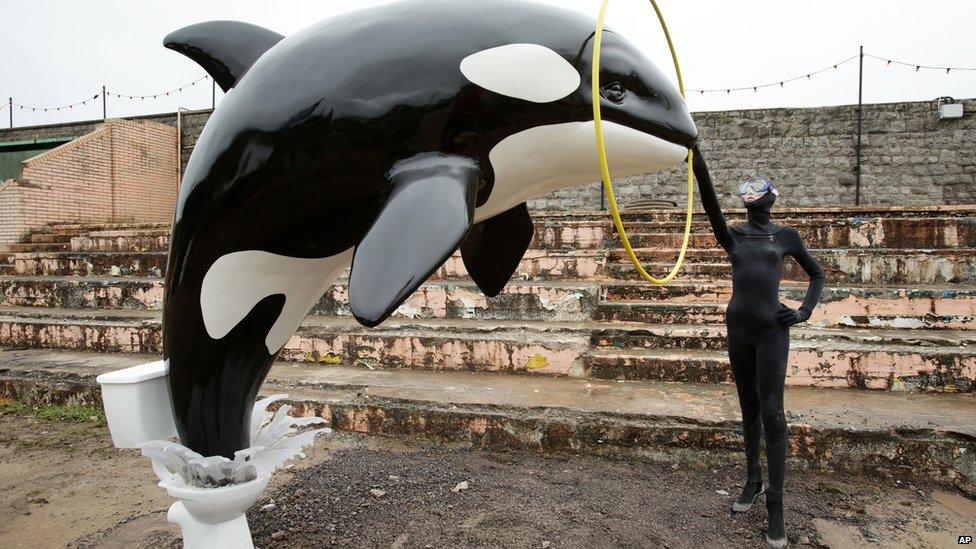

Described by Banksy as a “theme park unsuitable for children,” Dismaland ran from August 21 to September 27, 2015. Built under tight secrecy, the project transformed the Tropicana lido into a grim, decaying alternative to the squeaky-clean magic of Disneyland. The result was a surreal spectacle: a twisted fairytale world populated by deformed Cinderella carriages, riot vans turned into fountains, and dead-eyed employees trained to frown and sigh at every visitor.

The park featured over 50 artists from around the world, including Damien Hirst, Jenny Holzer, and Jimmy Cauty, among others. The artworks touched on themes like climate change, war, police brutality, the refugee crisis, celebrity culture, and surveillance. All of it presented through a lens that was equal parts absurd and unsettling.

But Dismaland wasn’t just about the art—it was about the environment. The queues, the confusing signage, the underwhelming rides—it was all part of the performance. Visitors weren’t just viewing art; they were living inside the critique.

Satire, Irony, and Anti-Consumerism

At its core, Dismaland was an ironic inversion of Disneyland, arguably one of the most iconic and sanitized symbols of Western consumer culture. Disney parks promise fantasy and escape; Dismaland delivered discomfort and confrontation. Where Disneyland masks the messiness of the world behind polished smiles and fireworks, Dismaland exposed that very mess—and dared you to laugh at it.

Banksy’s distaste for corporate control, mass media manipulation, and the commodification of culture was on full display. The park was littered with broken attractions, decaying architecture, and apathetic staff—a clear mockery of manufactured joy. Even the merchandise, with items like black balloons that read “I Am An Imbecile,” mocked the idea of souvenir culture itself.

By playing with the tropes of amusement parks, Banksy didn’t just parody Disney; he questioned the values these institutions uphold—comfort over truth, escapism over awareness, and profit over authenticity.

Refugee Crisis and Political Urgency

Though filled with dark humor, Dismaland also had an urgent political heartbeat. One of the park’s most powerful installations was a grim sculpture of a boat packed with refugees, floating in a murky pool. It was a stark reference to the real-world humanitarian crisis unfolding across Europe, as thousands of people fled war and poverty, often dying at sea.

Banksy’s ability to intertwine real-time political events into his installations is a hallmark of his situational street art approach. This wasn’t just about aesthetic or shock value—it was about activating awareness. In this sense, Dismaland served as both a mirror and a megaphone, reflecting the world’s horrors while amplifying their absurdity.

After the exhibition closed, Banksy used materials and profits from Dismaland to fund a refugee camp in Calais, further proving that the project wasn’t just performative but actively contributing to change.

Situational Street Art on a Massive Scale

Dismaland wasn’t street art in the traditional sense—there was no graffiti on alleyway walls or stenciled rats on urban surfaces. But it absolutely belonged in the lineage of Banksy’s street-based interventions. Why? Because like his wall pieces, Dismaland was about context.

Street art, at its best, thrives in tension with its surroundings. It’s temporary, reactive, and subversive. Dismaland achieved all of these on a monumental scale. It transformed a real space with real people into a living critique of culture and politics. It was temporary by design, lasted just five weeks, and its impermanence only added to its impact.

Moreover, it was participatory. Visitors became part of the artwork. Their reactions, confusion, amusement, and discomfort were integral to the experience. This kind of immersion is at the heart of situational art—art that isn’t just seen, but lived.

The Art World Critique

Another layer to Dismaland was its critique of the art world itself. By inviting other artists and charging an affordable entry fee (£3), Banksy positioned Dismaland as both a major international exhibition and a people’s gallery. It questioned who gets access to contemporary art, who profits from it, and how it's consumed.

In traditional gallery settings, art is often framed as precious, elevated, and exclusive. Dismaland shattered that illusion. It brought together global talent in a dilapidated seaside resort, mixing fine art with carnival chaos. The experience was raw, disorienting, and democratic—more punk gig than biennale.

And yet, even in its anti-elitism, Dismaland attracted the same collectors, critics, and celebrities it mocked. It was a brilliant paradox: a rejection of art-world norms that became one of the year’s most talked-about cultural events.

Legacy and Influence

Dismaland was dismantled in late September 2015, but its impact lingers. It wasn't just an art project; it was a cultural moment. It bridged the gap between street art and installation, spectacle and substance. It proved that socially engaged art could also be wildly popular—and profitable, without losing its integrity.

For Banksy, Dismaland was a turning point. It expanded his scope from walls and alleys to environments, paving the way for later projects like The Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem—a functioning hotel overlooking the West Bank barrier, again combining art, politics, and space in a way only Banksy can.

Dismaland as a Statement and Strategy

Dismaland wasn't just an attack on theme parks, capitalism, or politics—it was a statement about experience. It invited visitors to step into a world where the ugliness of reality couldn't be ignored, even as it was cloaked in fairground lights and papier-mâché castles.

As a piece of situational street art, Dismaland epitomized Banksy's belief that art should disrupt, provoke, and exist beyond traditional frameworks. It was ephemeral, immersive, and deeply reflective of the world around it.

In the end, Dismaland did what all great street art does: it made people look twice, laugh nervously, and leave a little more awake than when they arrived.

Discover Banksy signed prints for sale and contact our galleries for further information to buy Banksy paintings via info@guyhepner.com or, if you’re looking to sell, find out how to sell Banksy prints. Discover more useful articles in How does Banksy Make Money? Who is Banksy? Banksy vs Warhol and The Most Expensive Banksy Artworks.