Keith Haring’s art is instantly recognizable: bold black lines, vibrant colors, and simplified, energetic figures that seem to pulse with life. While his style is often associated with spontaneity and accessibility, Haring’s work is underpinned by a sophisticated use of semiotics—the study of signs and symbols as elements of communicative behavior. Through his unique visual language, Haring crafted a powerful system of signs that transcended words, allowing his art to speak directly to diverse audiences. This article explores how Haring used line, form, and iconography to communicate deep social, political, and personal messages through the framework of semiotics.

Visual Language as Public Communication

From the outset of his career, Haring saw art not as a commodity confined to galleries but as a democratic medium for communication. Influenced by semiotic theories, particularly those of Roland Barthes and Ferdinand de Saussure, Haring recognized the power of signs in shaping meaning and cultural understanding.

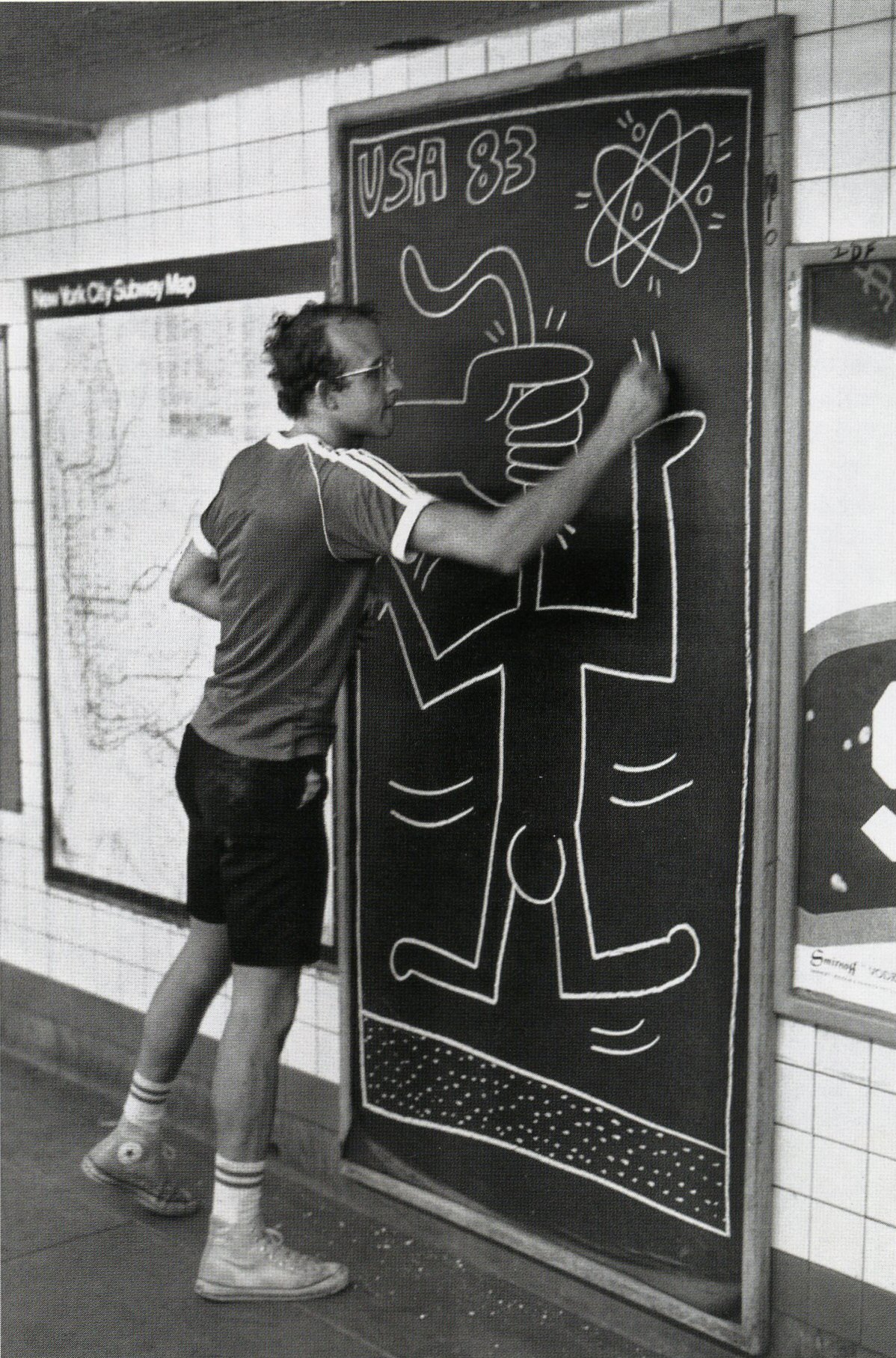

In the New York subways of the early 1980s, Haring began drawing with white chalk on unused black advertising panels. These became the canvas for his early pictograms—dogs, babies, flying saucers, televisions—all rendered in bold lines with minimal detail. To commuters, these icons were instantly readable, yet open to interpretation. This ambiguity is a hallmark of Haring’s semiotic strategy: the signs were polysemous, meaning they could hold multiple meanings simultaneously depending on context and viewer experience.

The Line as a Signifier of Life and Energy

At the heart of Haring’s visual vocabulary lies his line work. Far from being mere outlines, Haring’s lines serve as signifiers of energy, motion, and emotional intensity. His figures are rarely static; they jump, dance, vibrate, or radiate with life. Radiating lines around a figure might signify joy, spiritual energy, divine presence, or simply movement.

These emanata—lines or symbols emanating from a figure—are a staple of comics and street art, and Haring elevated them into powerful tools of expression. By eschewing shading and detail in favor of clean, confident contours, Haring imbued every figure with immediacy and urgency. His line became a living element, functioning as both a boundary and a bridge between forms.

Key Motifs and Their Semiotic Power

Haring developed a library of recurring symbols, each carrying evolving meanings shaped by cultural context and repetition. Some of the most potent include:

Radiant Baby

The Radiant Baby, perhaps Haring’s most iconic motif, symbolizes purity, potential, and divine energy. With rays emanating from its body, the baby is both sacred and subversive—celebrating innocence while also representing the new generation born into a world of both hope and crisis. Over time, the Radiant Baby became synonymous with Haring’s identity and mission.

Barking Dog

The Barking Dog functions as a warning, a prophet, or an agent of power. Its open mouth and jagged speech lines evoke protest or command. Sometimes the dog is benign; other times, aggressive or menacing. This mutability allows it to critique authority, police violence, or blind obedience, depending on the context.

Three-Eyed Monster

Often interpreted as a commentary on mutation, surveillance, or dehumanization, the Three-Eyed Monster speaks to fears of technological overreach and authoritarianism. In semiotic terms, the third eye, a traditional symbol of insight, becomes distorted—a sign of corrupted vision or unnatural evolution.

Flying Saucers

UFOs in Haring’s universe symbolize outside influence, alienation, and the mysterious forces shaping society. They can represent surveillance, state power, or the artist’s critique of social control. Their ambiguity makes them powerful signs—harbingers of either salvation or doom.

Televisions

Televisions appear frequently in Haring’s work, often as malevolent forces. These symbols critique mass media, propaganda, and cultural indoctrination. Figures mesmerized or entrapped by screens reflect Haring’s concern that media was shaping reality and dulling the public’s critical faculties.

![]()

Semiotics and Social Commentary

While Haring’s symbols are bold and simplified, their meanings are anything but. The semiotic power of his visual vocabulary is magnified by his commitment to social justice, queer identity, anti-racism, and AIDS awareness. For Haring, symbols were not just aesthetic choices—they were vehicles for activism.

In his 1989 work Silence = Death, created in the wake of the AIDS crisis, Haring places pink triangles (repurposed from Nazi persecution of homosexuals) above screaming heads. The piece uses stark, emotionally charged imagery to critique silence from governments, media, and the public. The pink triangle becomes a re-signified symbol—from oppression to resistance—while the screaming faces function as both victims and witnesses.

Similarly, his Ignorance = Fear series transforms abstract concepts into tangible visual messages. Figures with crossed-out mouths and ears embody the suppression of speech and understanding. In this case, the semiotic absence (a lack of open senses) is just as telling as the presence of any symbol.

Accessibility and the Deconstruction of High Art

Haring’s symbols were not meant to be elitist. Drawing on street art, children’s books, comics, and ancient petroglyphs, Haring collapsed the barriers between high and low art. This semiotic flattening made his work accessible to children, art historians, activists, and subway riders alike. By eliminating traditional narrative and linguistic constraints, Haring invited participation: viewers became interpreters, co-creators of meaning.

In this way, Haring’s work aligns with Barthes’ notion of the “death of the author”—a rejection of fixed, singular meanings in favor of multiplicity. His pictographic style encouraged each viewer to decode according to their own knowledge and experience, turning interpretation into a democratic act.

The Body as Text

Haring also frequently used the human body as both symbol and site of meaning. His genderless, faceless figures resist specificity, making them universal. Yet they also carry profound significance: they are born, dance, die, love, fight, mutate. Haring used the body to explore themes of mortality, sexuality, oppression, and transcendence.

In works that show bodies transforming—becoming machines, merging with dogs, or exploding into lines—Haring visualizes how external systems (government, media, disease) intrude upon the self. This interplay between the biological and the symbolic reinforces the idea that no body is ever neutral—it is always marked by power structures.

A Living, Breathing Semiotic System

Keith Haring’s legacy lies not just in his aesthetic or political impact, but in his mastery of semiotics as visual activism. His line was never just a line; it was a pulse, a current of meaning. His symbols, while simple on the surface, function as complex carriers of cultural critique, personal truth, and collective hope.

More than three decades after his death, Haring’s visual language remains alive. It speaks in classrooms, in galleries, on protest signs, and on public walls. It reminds us that art can be both a mirror and a megaphone—and that even the most basic sign, drawn with chalk on a subway wall, can ignite a revolution.

Discover our selection of Keith Haring paintings for sale and contact info@guyhepner.com for latest availabilities. Thinking of selling? We can help. Speak to our teams to find out how to sell Keith Haring prints. Looking for more Keith Haring content? Read out latest articles on Keith Haring's New York, our Guide to collecting Haring and the politics of Keith Haring.