Keith Haring was more than a pop artist. Beneath his signature bold lines, vibrant colors, and cartoon-like figures lay a body of work that was deeply political and unafraid to confront the urgent issues of his time. From the AIDS epidemic and apartheid to capitalism, homophobia, and nuclear disarmament, Haring used his art as a powerful platform for social commentary. While his style made his work accessible to broad audiences, the messages embedded in his imagery were pointed, urgent, and unapologetically activist.

AIDS Awareness and Advocacy

Keith Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, but his activism around the epidemic began well before his own diagnosis. At a time when AIDS was still heavily stigmatized and under-researched, Haring became one of the few public figures in the art world to confront the disease head-on in his work.

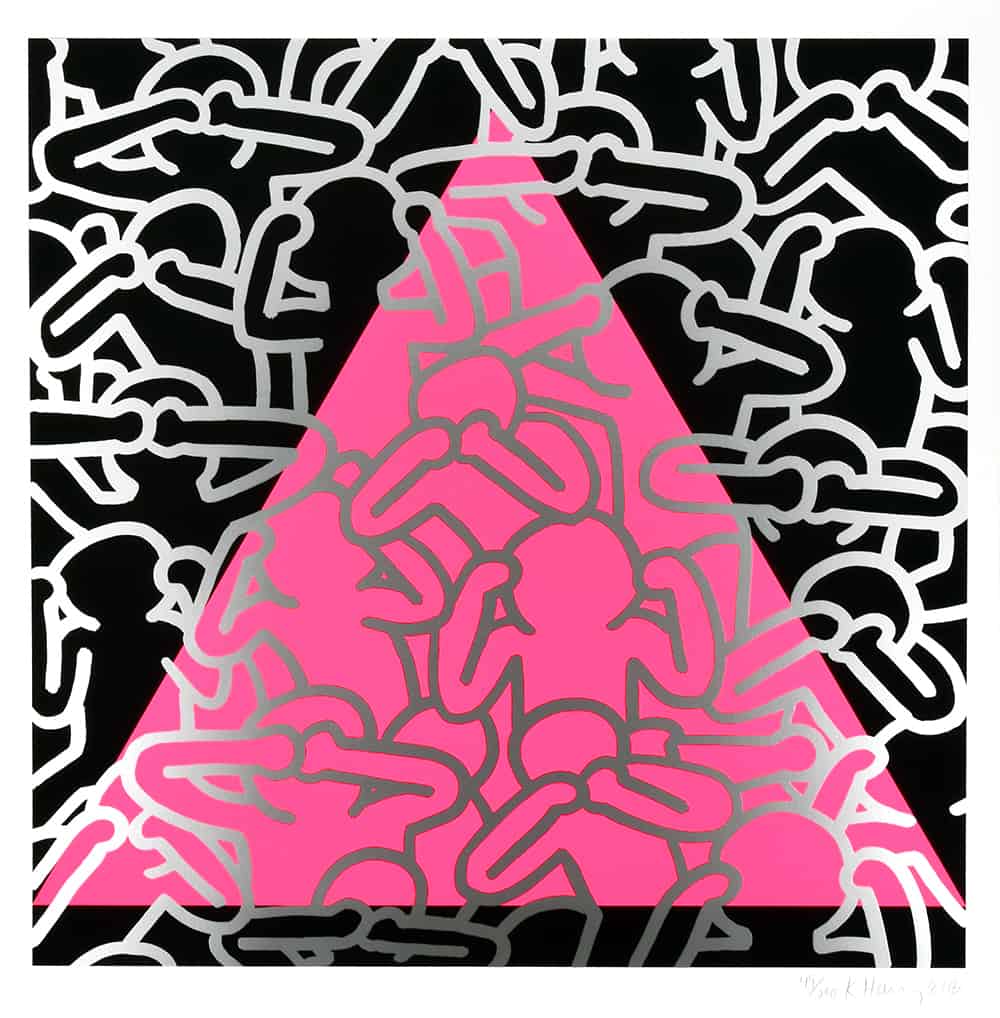

One of his most well-known activist pieces is "Silence = Death" (1989), which borrowed the pink triangle symbol originally used by the Nazis to identify homosexuals and later reclaimed by the LGBTQ+ community during the AIDS crisis. The work features the phrase “Silence = Death” in bold text above Haring’s signature figures, some covering their eyes, ears, and mouths—an indictment of government inaction and social denial around the epidemic.

Another powerful piece is “Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death” (1989), a screenprint that became a poster distributed widely by ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). This piece again uses bold imagery and repetition to hammer home the dangers of inaction. The message was clear: ignoring AIDS wasn’t neutral—it was deadly.

Haring also created “Rebel With Many Causes”, a self-portrait that summarized his identity as an artist who fought not just for gay rights, but against the disease that was devastating his community. His Foundation, created in 1989 shortly before his death, continues to support AIDS-related charities to this day.

Anti-Apartheid

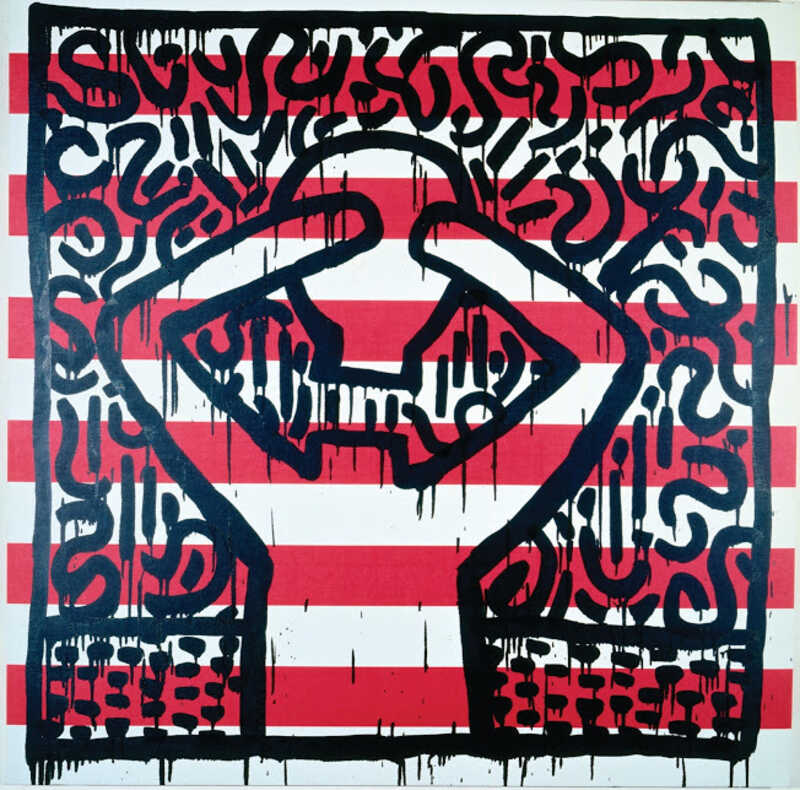

Haring’s political reach extended globally, and he was vocal in his opposition to apartheid in South Africa. One of his boldest anti-apartheid works is a poster titled “Free South Africa” (1985), created during the height of international protests against the apartheid regime.

In this work, Haring presents a powerful visual metaphor: a large Black figure is being crushed beneath the weight of a white authoritarian figure wielding a billy club. The artwork is deceptively simple but deeply evocative, emphasizing the brutality of the apartheid system. By circulating this image widely in poster form, Haring amplified international calls for racial justice and civil rights in South Africa.

He believed that artists had the responsibility to speak up about injustices beyond their immediate borders. “The role of the artist is to be a political being,” Haring said. “To make art that is about people, about life, about the world.”

Nuclear Disarmament

Another recurring theme in Haring’s politically charged works is the threat of nuclear war—a fear that loomed large during the Cold War era. His series “Radiant Baby”, which became one of his most iconic symbols, is often interpreted as a symbol of hope and purity. Yet, Haring juxtaposed such innocence with darker themes in works that warned of mankind’s self-destructive tendencies.

In pieces like “The Apocalypse” series (1988), Haring’s linework takes a more chaotic and apocalyptic tone. Inspired by William S. Burroughs’ text of the same name, the series features surreal, nightmarish imagery: mushroom clouds, skeletal figures, and exploding heads. The nuclear age, for Haring, wasn’t just a political problem—it was a spiritual and existential crisis, one that threatened the very survival of humanity.

Capitalism and Consumerism

Haring was critical of unchecked capitalism and the dehumanizing effects of consumer culture. While he famously opened the Pop Shop in 1986—a retail store selling his art on t-shirts, buttons, and posters—this was a deliberate move to democratize access to art, not an embrace of consumerism. He was deeply skeptical of commodification and its impact on society.

His painting “Untitled (1981)” features barking dogs, TVs with dollar signs, and robotic figures—symbols Haring often used to critique the mechanical, obedient nature of consumer behavior. He believed that advertising and media were tools of control, and his work often questioned who held power in society and how they manipulated public perception.

His use of repetition and symbols like the dollar sign, the television set, and the barking dog helped create a visual vocabulary that mocked and exposed the absurdity of capitalist propaganda.

Children’s Rights and Education

Although Haring's art tackled serious and often grim subjects, he was equally passionate about spreading joy and hope—especially to children. He believed children had an innate ability to understand and appreciate art, and he dedicated much of his later life to creating public murals and works in schools, playgrounds, and hospitals.

His “Crack is Wack” mural (1986), painted illegally on a handball court in Harlem, was a direct response to the crack epidemic that was ravaging urban communities—particularly among youth. The mural features frantic, exaggerated figures and bold lettering that delivers a clear message: drug abuse is destructive. Despite being initially painted without permission, the mural was so well-received that it was preserved and later restored.

Through works like this, Haring combined art, education, and activism in a way that was immediate and effective, particularly for marginalized communities.

LGBTQ+ Rights and Identity

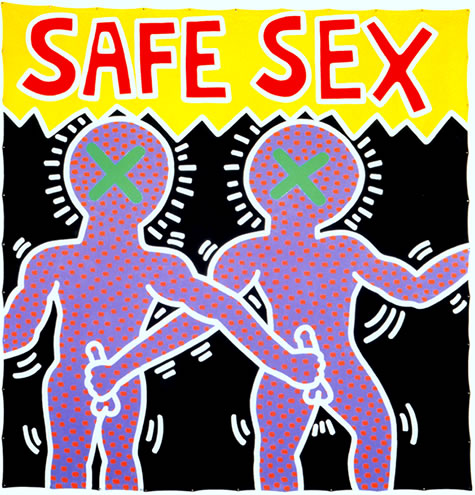

As an openly gay artist in the 1980s, Haring’s work often celebrated queer identity while also confronting the violence and marginalization faced by LGBTQ+ individuals. His public persona and artwork helped normalize gay identity at a time when the community was heavily stigmatized.

Pieces like “Safe Sex” (1987), which includes imagery of condoms and sexual figures, promoted safe sex practices without shame. He used his visibility and art to advocate for sexual health, body positivity, and the right to love freely. Haring’s refusal to sanitize his art made him a vital voice during a decade defined by both queer celebration and tragedy.

A Legacy of Art as Activism

Keith Haring’s work remains a testament to the power of visual language to effect social change. His simple, accessible style allowed complex and sometimes controversial ideas to reach a broad audience. Rather than using art as an escape from the world’s problems, Haring dove directly into them, believing that art could—and should—be used to address injustice, raise awareness, and demand better.

As he once put it:

“Art is nothing if you don’t reach every segment of the people.”

Haring’s political works are more than relics of 1980s activism; they are blueprints for how artists today can engage with the world—not from the sidelines, but at its most urgent intersections. His art continues to inspire new generations to pick up the pen, the brush, the spray can—and use it to speak truth to power.

Discover our selection of Keith Haring art for sale and contact info@guyhepner.com for latest availabilities. Thinking of selling? We can help. Speak to our teams to find out how to sell Keith Haring prints.