When Andy Warhol unveiled his Campbell’s Soup Cans in 1962, the art world did not know what had hit it. The debut of thirty-two hand-painted canvases, each depicting a different variety of Campbell’s soup, lined up side by side like a grocery store shelf, was an aesthetic shockwave. The arrangement was uniform, the colours crisp and clean, the imagery instantly recognizable to every American who had ever opened a kitchen cupboard. Yet it was presented not in a supermarket aisle, but in the sanctified, white-walled space of a Los Angeles gallery.

For some, the work was an insult to the fine arts — a lazy reproduction of a corporate design, unworthy of serious attention. For others, it was a conceptual coup — a brilliant distillation of post-war American culture into a single, endlessly repeated image. In one stroke, Warhol had managed to merge the language of advertising with the traditions of painting, placing the mundane on the same level as the masterpieces of the past. It was a declaration that anything — even the most ordinary object — could be art, provided it was framed and presented as such.

The Origins: Lunch as a Conceptual Framework

Warhol’s choice of subject was deeply personal and deceptively simple. He claimed to have eaten Campbell’s soup for lunch every day for over twenty years. In interviews, he half-joked about this routine, but in reality, it provided a conceptual foundation for the work. The soup can became a symbol not only of his own habits but of the habits of an entire nation — a post-war America where consumer products were standardized, branding was king, and repetition was both a comfort and a marketing strategy.

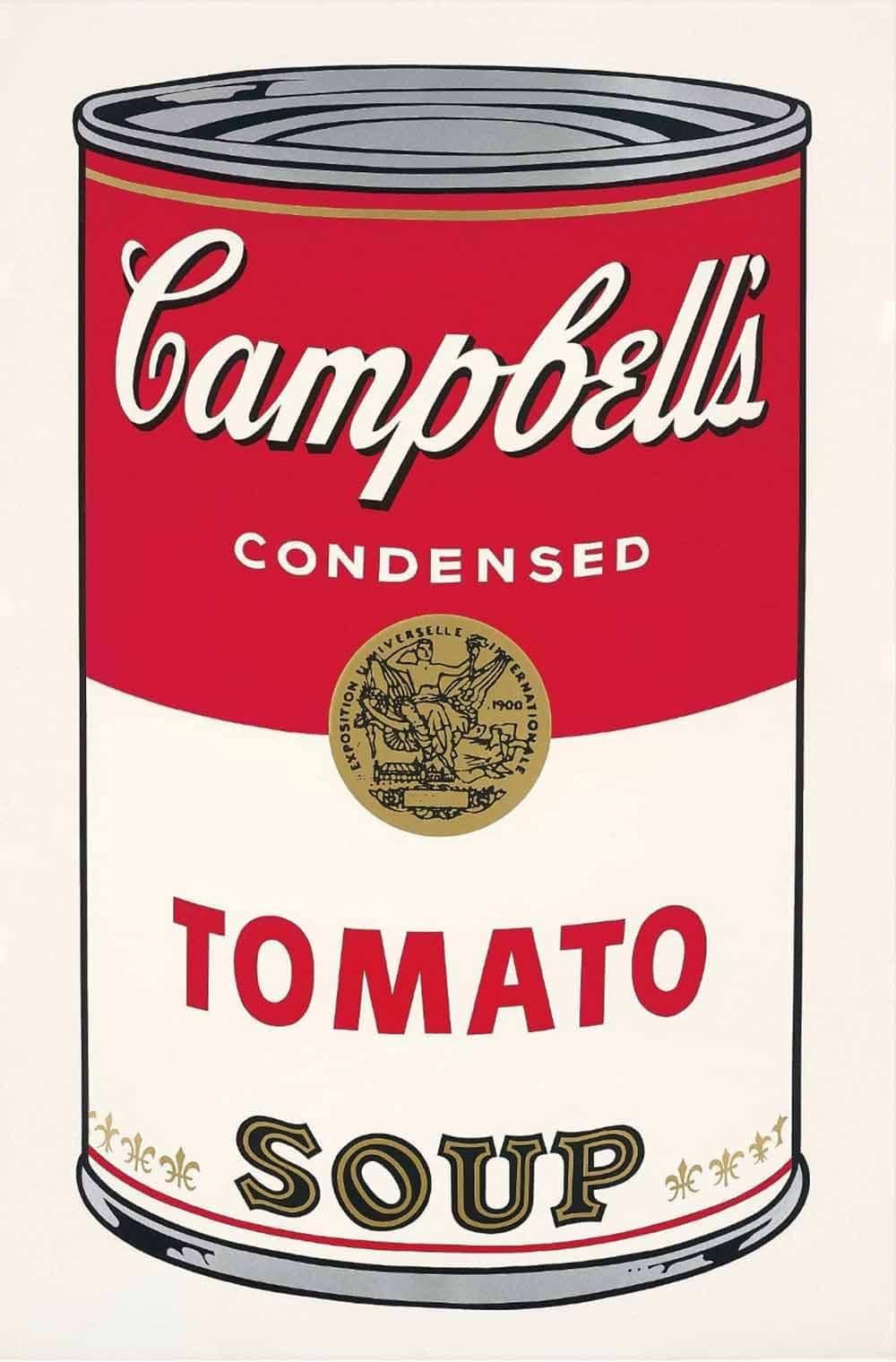

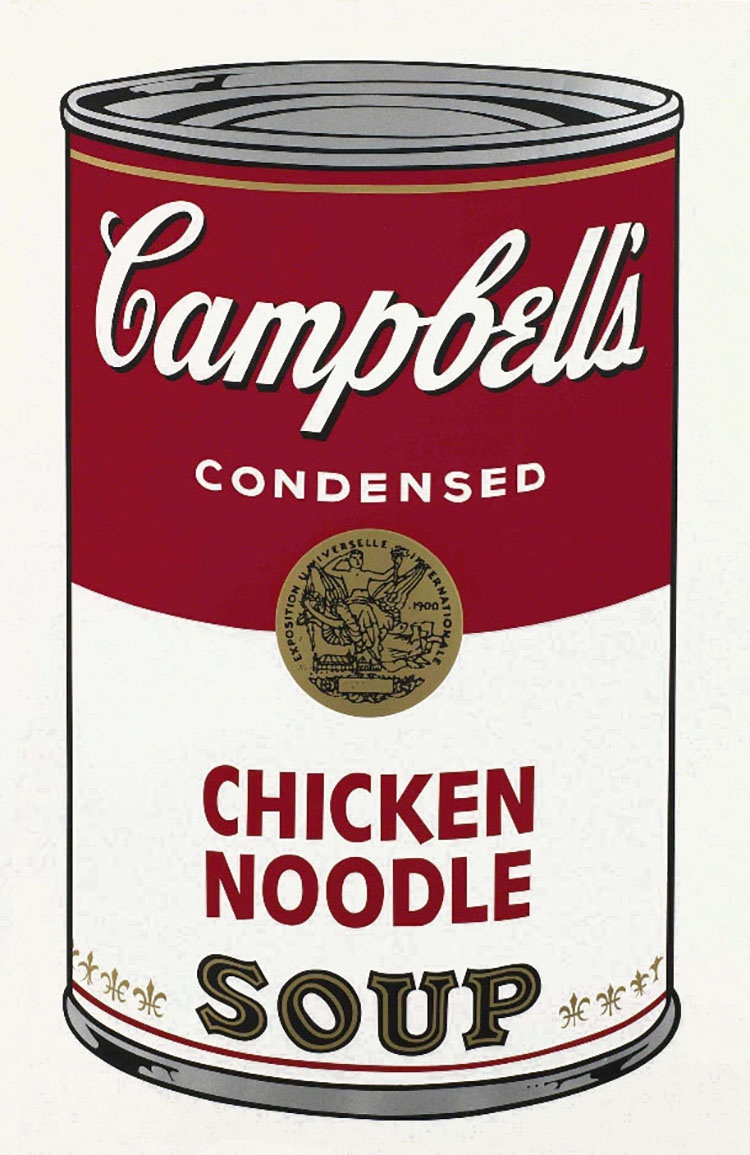

The Campbell’s label itself, with its red-and-white banding, gold medallion, and cursive script, was a triumph of mid-century design. It was instantly legible from a distance, visually consistent across varieties, and designed to convey reliability. This was precisely what made it so ripe for Warhol’s appropriation: the packaging was already an icon of mass culture before he ever touched a brush.

The Art World in 1962: A Scene Ripe for Disruption

When Warhol entered the fine art world, the dominant force in American painting was Abstract Expressionism. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were celebrated for their gestural brushwork, their emphasis on personal expression, and their belief in the canvas as a site of existential struggle. Their paintings were one-of-a-kind, unrepeatable, charged with the physical presence of the artist.

Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans could not have been more different. The brushwork was invisible. The image was borrowed, not invented. The repetition was deliberate and unapologetic. By removing the hand of the artist from the process — or at least concealing it — Warhol undermined the romantic notion of the artist as a heroic, solitary genius. Instead, he aligned himself with the logic of the factory, the printing press, and the advertising agency.

From Painting to Print: The Mechanization of Art

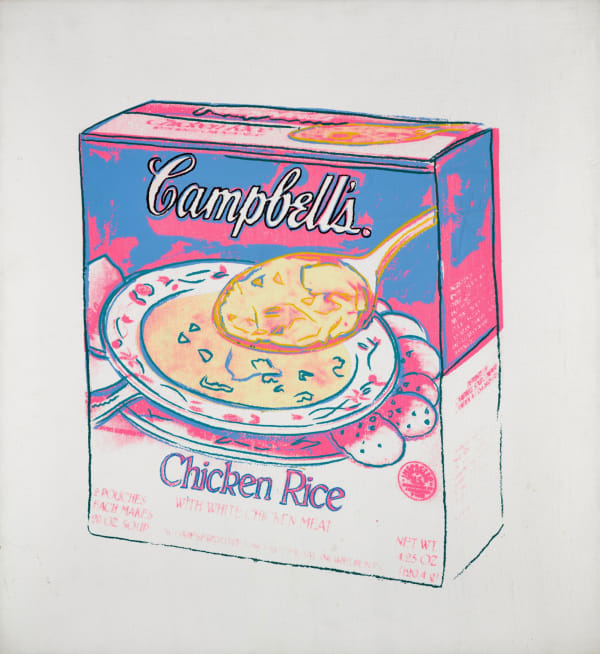

The original thirty-two canvases were painted by hand, though with a precision that made them look machine-made. But Warhol quickly realized that his vision would be better served by a more explicitly mechanical process. By the mid-1960s, he had embraced silk-screen printing — a commercial technique used in advertising and signage — to create multiple iterations of the same image with minimal variation.

In 1968 and 1969, Warhol produced two portfolios of Campbell’s Soup Cans, each containing ten different varieties. These were published through Factory Additions, his own print-publishing enterprise. The choice to issue these works as editions was conceptually integral: they were not limited to a single original but could be reproduced, purchased, and owned by many people — much like the product they depicted.

For Warhol, the method was the message. By using the same techniques that advertising used to flood the public with imagery, he blurred the boundary between art and commerce. The image of the soup can was no longer just a subject; it was also a metaphor for how art itself could be packaged and consumed.

The Reception: Shock, Outrage, and Gradual Acceptance

At the time of its debut, Campbell’s Soup Cans was met with a mixture of amusement, disdain, and intrigue. Many critics accused Warhol of being derivative, a mere copyist of a commercial design. Others, particularly younger artists and curators, recognized that he was doing something radical — stripping art of its elitist pretensions and grounding it in the imagery of everyday life.

The work was quickly associated with the burgeoning Pop Art movement, which also included figures like Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and James Rosenquist. Together, these artists challenged the high-low divide in art, taking their cues from comic books, advertisements, and supermarket shelves rather than myth, religion, or personal expression.

Art Historical Context: From Duchamp to Pop

Warhol’s soup cans did not appear out of nowhere. In many ways, they were a continuation of the conceptual revolution sparked by Marcel Duchamp in the early 20th century. Duchamp’s readymades — most famously his 1917 Fountain, a urinal presented as art — had already posed the question: “What makes something a work of art?” Warhol’s answer was different from Duchamp’s, but equally provocative. Whereas Duchamp used industrial objects to mock the art world, Warhol embraced the industrial aesthetic, treating it not as satire but as subject matter worthy of fascination.

In doing so, he also connected his work to the traditions of still-life painting, albeit in an inverted form. Where 17th-century Dutch painters meticulously depicted fruit, flowers, and tableware as symbols of wealth and mortality, Warhol depicted a mass-produced can of soup as a symbol of 20th-century consumerism. His still life was not a celebration of abundance in the old sense, but a portrait of industrial abundance — the abundance of identical units rolling off an assembly line.

Repetition as Meaning

The repetition in Campbell’s Soup Cans is not simply a formal choice; it is the work’s central meaning. By presenting thirty-two varieties side by side, Warhol forces the viewer to confront both the sameness and the small differences within mass production. The slight shifts in lettering, the presence or absence of a fleur-de-lis, the different flavour names — these variations become significant only because they are set against a backdrop of overwhelming uniformity.

This interplay between uniformity and difference reflects the paradox of consumer culture: products are designed to be identical to build brand consistency, yet they must also offer the illusion of choice. Warhol captures this paradox with a precision that is both visual and conceptual.

The Market Legacy: From Counterculture to Commodity

Ironically, a work that questioned the relationship between art and commerce became one of the most commercially successful bodies of work in modern art. The original paintings are now among the most valuable in Warhol’s oeuvre, and the screen print portfolios are fixtures of the contemporary print market.

Collectors value them not only for their aesthetic and conceptual importance but also for their role in legitimizing editioned works as fine art. Before Warhol, multiples were often considered less valuable than unique works; after Warhol, they became central to the contemporary art economy.

Influence on Contemporary Art

The influence of Campbell’s Soup Cans can be seen in the work of countless contemporary artists. Jeff Koons’s balloon dogs, Damien Hirst’s spot paintings, and Banksy’s ironic appropriations of corporate imagery all owe a debt to Warhol’s insistence that mass-produced symbols could carry artistic weight. The idea that an artwork could exist as a brand, replicated across mediums and contexts, is now a standard part of the art world’s operating logic.

The Digital Age: Warhol’s Prescience

In the era of Instagram, TikTok, and meme culture, Warhol’s vision seems almost prophetic. He anticipated a world in which images are endlessly reproduced, remixed, and shared, often divorced from their original context. The soup can, once a supermarket product, is now a floating signifier — a meme, a T-shirt graphic, a museum icon. Its meaning is fluid, shaped as much by its circulation as by its content.

Why the Soup Cans Still Matter

More than sixty years after their debut, Campbell’s Soup Cans remains one of the most recognisable series in art history. Its endurance lies in its ability to operate on multiple registers: as a personal statement about the artist’s life, as a formal experiment in repetition and variation, as a social commentary on consumerism, and as a conceptual provocation about what constitutes art.

Standing before a wall of Warhol’s soup cans today, one is confronted with an image that is both utterly ordinary and profoundly symbolic. It is the face of an era — an era defined by the supermarket, the television ad, the product line, and the brand. Warhol captured that face with clarity, wit, and an unblinking eye, transforming the soup can into one of the great icons of modern culture.

Discover andy warhol signed prints for sale and contact info@guyhepner.com for latest availabilities. Looking to sell? speak to our team on how to sell andy warhol prints.