-

Artworks

Pablo Picasso

Tête de faune, 1958Coloured wax crayons on paper

Signed and numbered12 x 10 in

30.5 x 25.4 cmSeries: DrawingCopyright The ArtistPablo Picasso’s Tête de faune (Head of a Faun), created on April 14, 1958, is a vivid, electrifying work that exemplifies the artist’s capacity to fuse mythological symbolism with unrestrained...Pablo Picasso’s Tête de faune (Head of a Faun), created on April 14, 1958, is a vivid, electrifying work that exemplifies the artist’s capacity to fuse mythological symbolism with unrestrained modernist expression. Executed in coloured crayon, the drawing pulses with vitality and intensity, depicting the legendary faun—a creature of nature and mischief from Greco-Roman mythology—with frenetic energy and childlike immediacy. Despite its apparent simplicity, the work is saturated with historical resonance, emotional power, and formal invention.

The composition bursts with jagged, swirling lines in green, yellow, purple, pink, and blue. These vibrant strokes coalesce into a facial form, wild and hypnotic, with wide, staring eyes, a flared nose, and a writhing beard. Horn-like shapes or tufts of hair frame the head in a radiant halo of zigzagging energy, making the faun appear as a force of nature itself—fiery, animalistic, and alive.

Picasso uses colour like electricity. Rather than modelling form through volume or shading, he builds it through overlapping lines and directional tension. The eyes anchor the composition with a stark black intensity, while the rest of the face vibrates outward, as if caught mid-transformation—between man and beast, god and animal.

The drawing’s linear style and crayon medium recall both children’s art and ancient frescoes, but the sophistication of Picasso’s mark-making is unmistakable. The chaos is calculated; the imbalance, intentional. The faun is both grotesque and comical—simultaneously wise, wild, and possibly lecherous, as is often the case with Picasso’s mythic male archetypes.

The faun is a recurring figure in Picasso’s oeuvre, appearing most prominently in his celebrated Vollard Suite (1930s) and in numerous later works. It belongs to a pantheon of mythic characters—including minotaurs, centaurs, and muses—that allowed Picasso to explore primal instincts: desire, creation, destruction, and the tensions between civilization and nature.

Unlike the tormented minotaur of earlier years, Picasso’s fauns from the 1950s are often playful, sensual, and unrepentantly hedonistic. They symbolize not only the artist’s identification with the animal-man—creative, lustful, and unbound—but also his joy in spontaneity and invention. In Tête de faune, the mythical creature becomes a kind of self-portrait: fiery, uncontained, and utterly singular.

This work also reflects Picasso’s deep engagement with Mediterranean culture and mythology, especially after settling in the South of France. Surrounded by classical ruins and bathed in Mediterranean light, Picasso found renewed inspiration in antiquity—not through reverence, but through radical reinterpretation.

By the late 1950s, Picasso was embracing mediums that allowed for speed, improvisation, and directness. Crayon, pencil, and felt-tip pen became essential tools in his graphic vocabulary. These works were often executed in bursts of creative energy, with Picasso working rapidly, instinctively, and prolifically.

Tête de faune reflects this urgency. It is not a polished, formal drawing, but a raw transmission of emotion and myth through gesture. The coloured lines, unblended and immediate, evoke a kind of visual jazz—each mark a note, each colour a rhythm in a composition that is more expressive than illustrative.

Tête de faune is a dazzling example of Picasso’s ability to channel ancient myths through the lens of modern expression. In a flurry of coloured lines, he summons a creature who is part god, part animal, and part artist. The drawing captures a moment of pure vitality, collapsing the boundaries between form and energy, myth and self. It is a late work in spirit and date, but youthful in its execution—evidence of Picasso’s undying commitment to creation as a wild, sacred act.

For more information, contact our galleries via the inquiry form below.

%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22artist%22%3EPablo%20Picasso%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22title_and_year%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_title%22%3ET%C3%AAte%20de%20faune%3C/span%3E%2C%20%3Cspan%20class%3D%22title_and_year_year%22%3E1958%3C/span%3E%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22medium%22%3EColoured%20wax%20crayons%20on%20paper%3Cbr/%3E%0ASigned%20and%20numbered%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22dimensions%22%3E12%20x%2010%20in%3Cbr/%3E%0A30.5%20x%2025.4%20cm%3C/div%3E%3Cdiv%20class%3D%22series%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22artwork_caption_prefix%22%3ESeries%3A%3C/span%3E%20Drawing%3C/div%3E1of 12Related artworks-

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960 -

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915 -

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954 -

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899 -

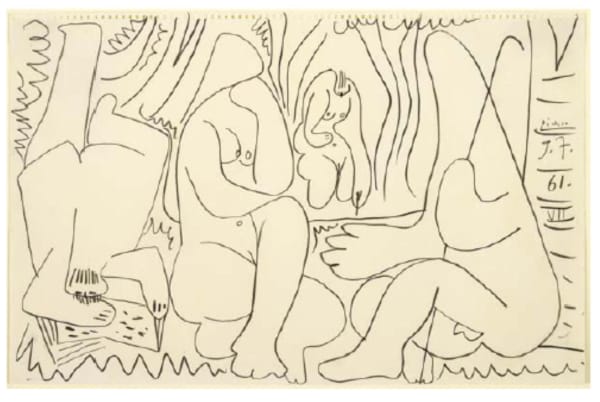

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961 -

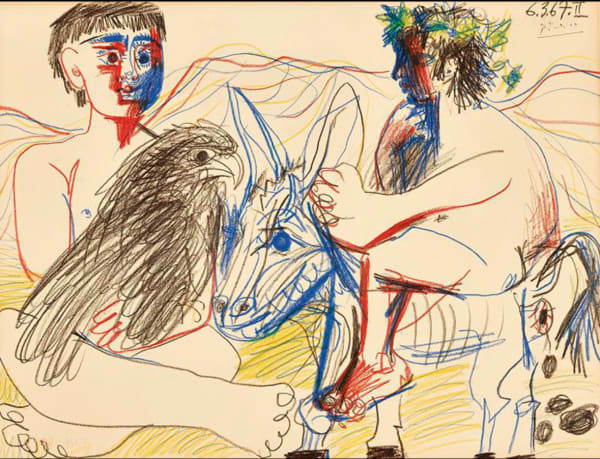

Pablo PicassoTeenager, eagle and donkey, 1967

Pablo PicassoTeenager, eagle and donkey, 1967 -

Pablo PicassoTrois hommes et femme nus, 1967

Pablo PicassoTrois hommes et femme nus, 1967 -

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages nus Assis, 1966

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages nus Assis, 1966 -

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926 -

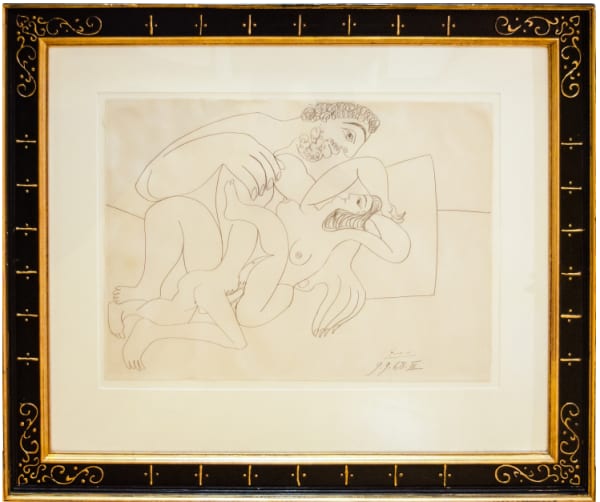

Pablo PicassoL’Etreinte, 1968

Pablo PicassoL’Etreinte, 1968 -

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961 -

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959 -

Pablo PicassoLe déjeuner, 1962

Pablo PicassoLe déjeuner, 1962 -

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoHomme Assis, 1971

Pablo PicassoHomme Assis, 1971 -

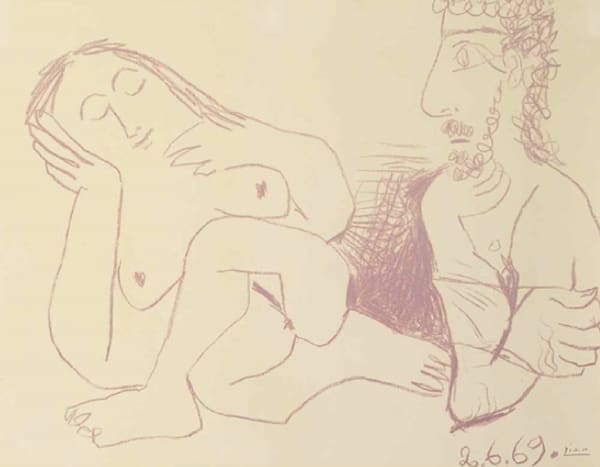

Pablo PicassoBust of Naked Man and Woman, 1969

Pablo PicassoBust of Naked Man and Woman, 1969

-

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Find out more about cookies.