Pablo Picasso

Signed and dated

35.6 x 22.9 cm

Homme Assis (Seated Man), drawn by Pablo Picasso on August 9, 1971, is a profound testament to the energy, wit, and fearless experimentation that defined his late period. Created less than two years before his death, this pencil drawing distills over 70 years of artistic innovation into a deceptively simple yet complex composition. In Homme Assis, Picasso turns to pure line, constructing a figure at once humorous, grotesque, and regal—offering a final meditation on identity, age, and the eternal dialogue between artist and subject.

At first glance, Homme Assis may seem childlike in execution—a tangled portrait sketched with unbroken, fluid lines. But beneath this economy of mark lies immense control and inventiveness. The seated figure’s head, hands, and body are flattened and fractured into overlapping planes, revealing multiple perspectives at once. This Cubist inheritance is not academic, but instinctive: the eyes look in different directions, the nose is split across planes, and the mouth and beard create a dark focal point, anchoring the play of shifting facial geometry.

The character’s massive hands, resting on his torso, are drawn with exaggerated emphasis—each digit clearly marked and the cuffs frayed with decorative zig-zag lines. The body, constructed from looping contours, suggests bulk and repose, while the thick shoulders and broad seat evoke a throne-like presence. This seated man, despite the apparent whimsy, carries the weight of myth, perhaps a king, a philosopher, or a self-portrait in disguise.

The drawing is done in graphite on tan card—a humble medium that enhances the raw immediacy of the work. The absence of color or shading places all emphasis on line, form, and gesture. Every stroke has purpose; nothing is superfluous. Even the date and signature, inscribed at the top left, become part of the composition, a record of time and authorship embedded in the image.

By 1971, Picasso was 90 years old. Far from slowing down, he entered a final creative explosion, producing drawings, prints, and paintings with ferocious energy. During this time, he frequently returned to the figure of the seated man—often depicted with wild beards, distorted faces, and theatrical poses. These were not merely character studies but archetypes: kings, matadors, philosophers, and artists. In many ways, they were self-portraits disguised in costume, reflecting Picasso’s contemplation of legacy, aging, and the mythos of the creator.

Homme Assis sits firmly within this body of work. The figure’s frontal presence, exaggerated hands, and mask-like face convey both authority and vulnerability. There is humor here, but also dignity. The man is not idealized but imagined—a composite of history, emotion, and invention.

This drawing is a masterclass in Picasso’s lifelong pursuit of expressive reduction. Where his early works were lush with painterly detail, his late pieces often strip down to essence—capturing the human condition in as few lines as possible. Homme Assis echoes his early Cubist experiments, the caricatured exuberance of his 1930s figures, and the psychological immediacy of his postwar portraits.

Picasso’s genius lies in this ability to evolve yet remain unmistakably himself. Even in this late period, he did not imitate past success but reimagined his forms through the lens of age, memory, and playful defiance.

Homme Assis is more than a portrait; it is a manifesto. With minimal means, Picasso creates a figure that is timeless, theatrical, and deeply human. It is the work of an artist unbound by tradition, embracing the final stage of life with wit, wisdom, and an undiminished passion for invention. Through a handful of lines on card, Picasso reminds us that drawing—at its most essential—is a form of seeing, thinking, and being.

For more information, contact our galleries via the inquiry form below.

-

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960 -

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915 -

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954 -

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899 -

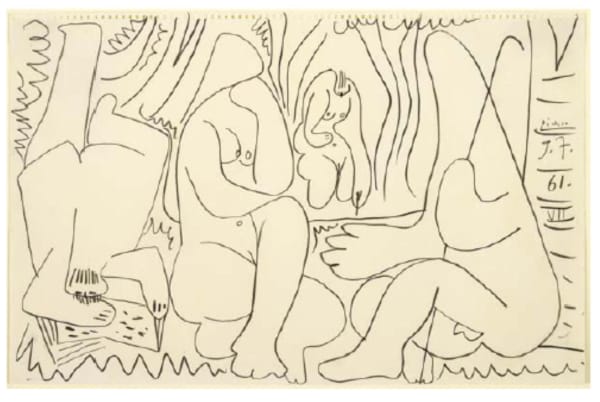

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoTête de faune, 1958

Pablo PicassoTête de faune, 1958 -

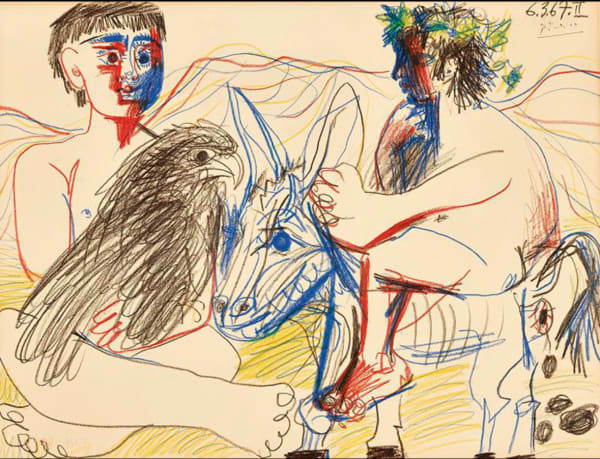

Pablo PicassoTeenager, eagle and donkey, 1967

Pablo PicassoTeenager, eagle and donkey, 1967 -

Pablo PicassoTrois hommes et femme nus, 1967

Pablo PicassoTrois hommes et femme nus, 1967 -

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages nus Assis, 1966

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages nus Assis, 1966 -

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926 -

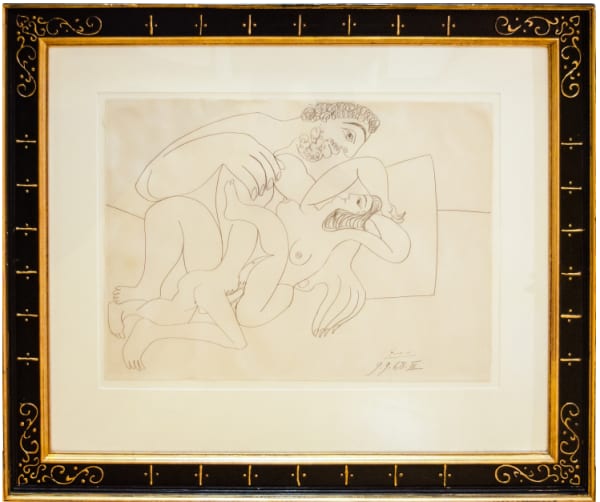

Pablo PicassoL’Etreinte, 1968

Pablo PicassoL’Etreinte, 1968 -

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961 -

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959 -

Pablo PicassoLe déjeuner, 1962

Pablo PicassoLe déjeuner, 1962 -

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961 -

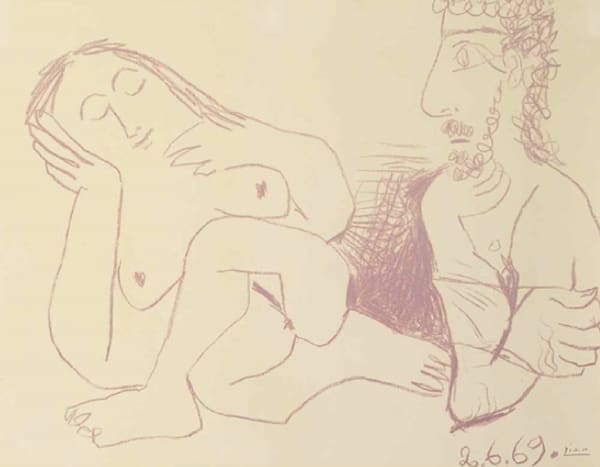

Pablo PicassoBust of Naked Man and Woman, 1969

Pablo PicassoBust of Naked Man and Woman, 1969

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Find out more about cookies.