Pablo Picasso

Signed and numbered

27 x 41.8 cm

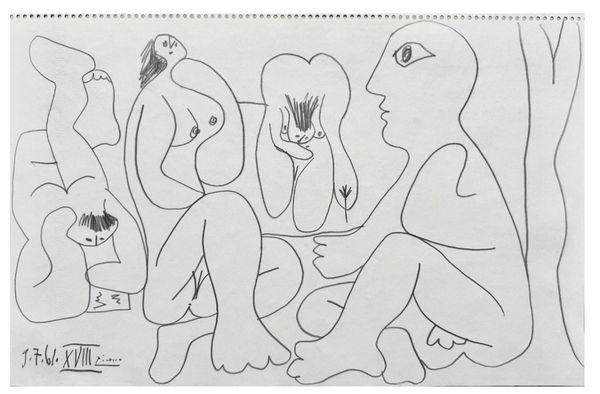

In this 1961 drawing, Le Déjeuner, Pablo Picasso engages in one of his most direct dialogues with art history, reinterpreting Édouard Manet’s iconic painting Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) through his own late-period visual language. Created with graphite on paper, this line drawing belongs to a series Picasso made between 1959 and 1962, exploring and reworking the 19th-century masterpiece with renewed sensuality, wit, and an almost primal immediacy.

The drawing is executed in sweeping, confident lines that capture a pastoral scene populated by three nude women and one clothed man, all seated in a stylised natural setting. Unlike Manet’s version, which still clung to a sense of representational space and classical figuration, Picasso’s treatment is intentionally abstracted and charged with erotic energy.

Each figure is exaggerated in scale and form. The women’s bodies are monumental, with bulbous breasts, exaggerated hips, and stylised pubic hair rendered with bold, almost humorous clarity. Their limbs are thick and rounded, and their poses project a curious mix of sensuality and awkwardness. The seated male, clothed and holding a cane, sits at the far right of the composition. His angular face and mask-like features evoke a sense of detachment, underscoring the dynamic tension between the observed and the observer.

The use of line is expressive and unbroken. Picasso draws not just figures, but a sense of energy and immediacy—trees swirl, grass spikes, and the figures seem to pulsate within the space. There is no shading, no depth perspective, and no realism in a traditional sense. Instead, the power of the drawing lies in its distilled, direct visual impact.

By stripping away the academic polish of Manet’s original, Picasso delivers a version that is more psychological than picturesque. The nude figures are unapologetically raw, their poses unidealised, their sexuality on display without modesty or symbolism. This echoes themes that ran through Picasso’s post-war and late works: eroticism, aging, memory, and his unrelenting curiosity about the human form.

The cane held by the male figure may symbolize age or authority, while his oversized hand points toward one of the women—perhaps evoking the viewer’s gaze or the artist’s own position as a voyeur or orchestrator of the scene. The reclining woman at left, with cascading hair, is almost goddess-like in her presence, anchoring the scene in both sensual and compositional terms.

This work reflects Picasso’s late style—free, instinctual, and rebellious. By the early 1960s, Picasso had abandoned the need to justify his place in the art world; instead, he was openly reinterpreting and even mocking the traditions that had defined Western art. His Déjeuners series is part of a broader project in which he also reimagined works by Velázquez (Las Meninas) and Delacroix (Women of Algiers), asserting himself as both inheritor and destroyer of tradition.

This sketch, with its spare yet potent composition, represents drawing not as preparation for a greater work, but as the work itself—a complete, energetic, and deeply personal artistic statement. In Le Déjeuner, Picasso reinvents an icon of modern art with a ferocity and freedom that can only come from a lifetime of mastery.

For more information, contact our galleries via the inquiry form below.

-

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960 -

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915 -

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954 -

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899 -

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926 -

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961 -

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959 -

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Find out more about cookies.