Pablo Picasso

Signed and numbered

27 x 42 cm

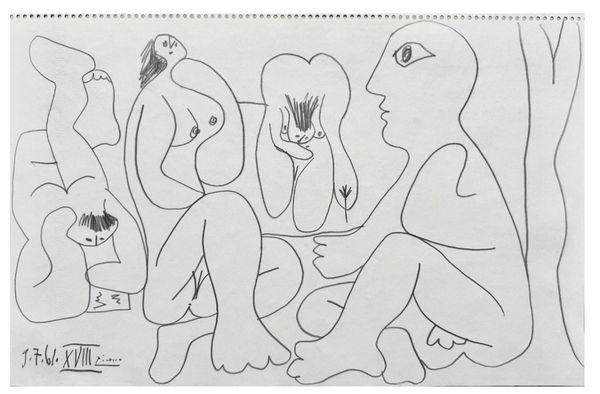

This drawing, part of Pablo Picasso’s Les Déjeuners series, exemplifies his remarkable late-period style—marked by erotic energy, playful irreverence, and a profound engagement with the art historical canon. Dated June 15, 1962, this work is one of many reinterpretations Picasso made of Édouard Manet’s 1863 painting Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, which had itself scandalized 19th-century audiences by placing a nude woman among clothed men in a contemporary setting. With this series, Picasso did not merely reinterpret Manet’s subject—he exploded it.

Executed in free-flowing graphite, the image is composed of thick, confident lines that outline five seated figures arranged in a dense, interlocking composition. At left, a voluptuous nude woman reclines, her exaggerated form drawn with humorous sensuality—pendulous breasts, rounded hips, and bold pubic hair sketched without inhibition. Opposite her, a monumental bearded male figure dominates the right half of the composition, legs splayed, hands open, eyes wide. Between them, three more figures—nude and semi-nude—occupy the space with playful abstraction. Their faces are cartoon-like, with Picasso’s characteristic bulbous eyes and minimalist detailing. An owl perches in the foliage at top left, an enigmatic motif often associated with wisdom, mystery, and perhaps Picasso’s own alter ego.

The composition is intentionally awkward, even grotesque. Limbs are oversized, bodies disproportionate. But this distortion is deliberate—it is Picasso at his most liberated, rejecting classical ideals in favor of expressive power. The use of line is masterful: fast, economical, yet immensely expressive. The background is indicated only by a few arched lines suggesting trees or canopy, allowing the figures to occupy an ambiguous, timeless space.

In his final decades, Picasso became increasingly interested in revisiting the great themes and compositions of Western art history. His Déjeuners drawings, produced between 1959 and 1962, reflect not only his admiration for Manet but also his irrepressible desire to reinvent. These were not homages; they were confrontations—Picasso inserting himself into the narrative of modernism and asserting his dominance.

The eroticism of the scene is a hallmark of Picasso’s late period. By the 1960s, his work had become openly carnal, humorous, and unrestrained. Sexuality, aging, voyeurism, and myth all became central themes. But rather than presenting these with gravitas, Picasso often adopted a tone of absurdity and satire, transforming historical reverence into bawdy visual theatre.

Les Déjeuners represents not just Picasso’s dialogue with art history, but also his persistent fascination with the human body and interpersonal dynamics. Here, the nude is no longer an object of beauty but a site of humor, absurdity, and raw physicality. The male figures—bearded and slumped—seem passive, dwarfed by the monumental energy of the women.

In this way, the sketch functions as both a personal meditation and a radical reinterpretation. It draws on memory, history, and instinct in equal measure. And though it appears casual, it is profoundly intentional—a summary of Picasso’s philosophy that art should challenge, provoke, and above all, remain alive.

Ultimately, this drawing is a manifesto of freedom—freedom from convention, from anatomy, from reverence—and a celebration of drawing as a vital, living act.

For more information, contact our galleries via the inquiry form below.

-

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960

Pablo PicassoThe Foot Bath | Le Bain de pieds, 1960 -

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915

Pablo PicassoFemme tenant un journal, 1915 -

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954

Pablo PicassoTrois Personnages,, 1954 -

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899

Pablo PicassoQuatre têtes d’élégantes (Four Elegant Heads), c. 1899 -

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes déjeuners,, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoLe déjeuner, 1962

Pablo PicassoLe déjeuner, 1962 -

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961

Pablo PicassoLes Dejeuners, 1961 -

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926

Pablo PicassoHomme et Femme, 1926 -

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961

Pablo Picasso·Toros, 1961 -

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959

Pablo Picasso·Étude pour la Suite Des Déjeuners III, 1959

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Find out more about cookies.